Caring for you, because they have to

Caring for you, because they have to

When Meredith Lange takes her mother, Suzanne, for a ride in the car, they count everything. The color red registers the most in Suzanne’s brain. As fall begins, the 69-year-old and her daughter look for red trees, bushes, flowers, the occasional silo, and every passing car. “She just likes to watch the world go by as we’re out riding,” Lange said. Suzanne has early onset dementia. Lange is her full-time informal caregiver, and across the country, she isn’t alone.

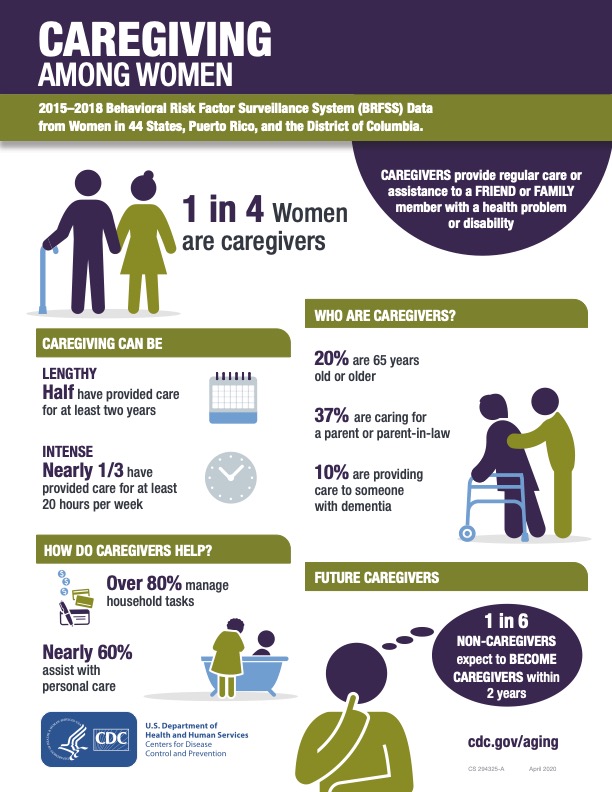

According to a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, one in four women in the U.S. are caregivers. Twenty percent of them are 65 or older. Half have provided care for at least two years, and nearly a third spend at least 20 hours per week caregiving.

Within the same study, 20% of caregivers in New York in 2019 were providing care for someone with dementia, which was an increase from 12% the previous year.

Six years ago, Lange’s mother was a long-haul truck driver. Lange said she had noticed some differences in her mother’s behavior as she got older but had difficulty getting her to see a doctor on a regular basis. Her mother miraculously survived a rollover accident with what looked like a concussion at the time, but doctors later diagnosed her with frontotemporal dementia. Lange said Suzanne’s steady truck-driving routine allowed her dementia to stay hidden, and the abrupt change in that pattern drastically changed her behavior in major ways.

After Lange moved her mother in with her, she said Suzanne would leave the house in the middle of the night, wandering the streets and rooting through garbage so she could “feed her critters.”

“She loves feeding the birds, and it started way back then,” Lange said. “And I’m like, ‘OK, but you can’t be doing this at two o’clock in the morning.’”

In 2016, Lange and her mother moved to Little York in Cortland County to be closer to family. While Lange is the primary caregiver who cooks, cleans, and dresses her mother, she has hired her aunt, cousin, and one other paid caregiver to look after Suzanne while Lange works at Upstate Community Hospital during the week and at night.

However, in the first few years, Lange slept on the couch outside her mother’s room, dozing on and off, and would get only four hours of sleep, waking at 2 or 3 a.m. to check on her mother before getting ready for work at 6 a.m. In January 2019, Lange was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.

“With the number of lesions that are on my brain, they said I probably had it for years and just didn’t know it,” Lange said.

Caregiver stress is something Sue Spina, a licensed social worker for local home care service Nascentia Health, sees every day. Spina said the caregivers she gets referrals for, who are mostly women, feel depressed, anxious, and overwhelmed.

“When you become a caregiver, depending on the diagnosis and the prognosis, you often neglect yourself,” Spina said. “When you push yourself aside, and you’re not acknowledging what your needs are, sooner or later, something is going to give.”

Informal caregivers are unpaid friends or family members who are providing regular care to someone with a health problem or disability. In 2017, when Joanne Crook’s husband Mark survived a stroke that paralyzed his left side, she retired early from her job as a 911 operator for Onondaga County to become his sole caregiver.

“I knew he needed 24-hour assistance. He had to be with somebody,” Crook said. “There was no way that I could work and take care of him. Even having somebody come in, that’s a big expense. I’d be working just to pay that person.”

While the act of caregiving and the need to become a caregiver can be different for everyone, Spina said the reason she believes caregiving falls on women more than men is because of society’s expectations.

“We’re evolving over time, but I think women are nurturing,” Spina said. “They have a sense of responsibility and duty. We always have that tendency to be different from the men in those regards.”

Although Crook’s husband can walk with a cane, he still needs help balancing himself when getting up and down, in addition to dressing and showering. Crook also does all the chores around the house. But her caregiver stress doesn’t come only from physically taking care of Mark.

“When he thinks that he can do something that I know he can’t, trying to tell him no but still trying to keep his spirits up is a stressful thing for me,” Crook said. “It’s the little things that really bug me. Everything takes a lot longer than it used to.”

Renee Moonan, an account executive for Eagle Newspapers, is the main caregiver for her 95-year-old father Gilbert Bonin, along with her sister, brother and four paid caregivers. Moonan’s caregiver experience began when her mother’s health started to decline, and her last few years in and out of nursing homes before she died in 2018 convinced the family to transition their father to home care.

After a lot of reassurance, Moonan’s father enjoys the paid caregivers who bring him food and clean his house. All of his caregivers leave notes in a notebook on the kitchen table that record his daily blood pressure, pulse, weight, overall mood and housekeeping reminders about doing the dishes or laundry. Now, her father is thriving on his care plan, and as his caregiver, Moonan said it’s easier to take care of him when he’s in his own home.

“Everything about his care is managed,” Moonan said. “It’s unfortunate because that’s what my mom needed, but we just weren’t strong enough. The better care is definitely at home.”