Hurricanes Fiona and Ian point to broader environmental issues, scientists say

Hurricanes Fiona and Ian hint at broader environmental issues

Two massive storms made landfall in U.S. territory within the span of 10 days, raising the alarm across the country about the frightening impacts of human-induced climate change. Critics argue that the frequency of storms like this is typical of what is called ‘hurricane season.’ It is not the frequency, however, with which the storms occur that is causing experts to worry.

“It is possible to get two storms coming through the tropical Atlantic during storm season,” said Dr. Tripti Battacharya, an assistant professor in Earth Sciences at Syracuse University, “That being said, we saw some unusual things with both these storms that point to a broader issue.”

Battacharya pointed to what climate dynamicists call potential intensity.

“It essentially measures the ability of the local climate to fuel a strong storm,” she said.

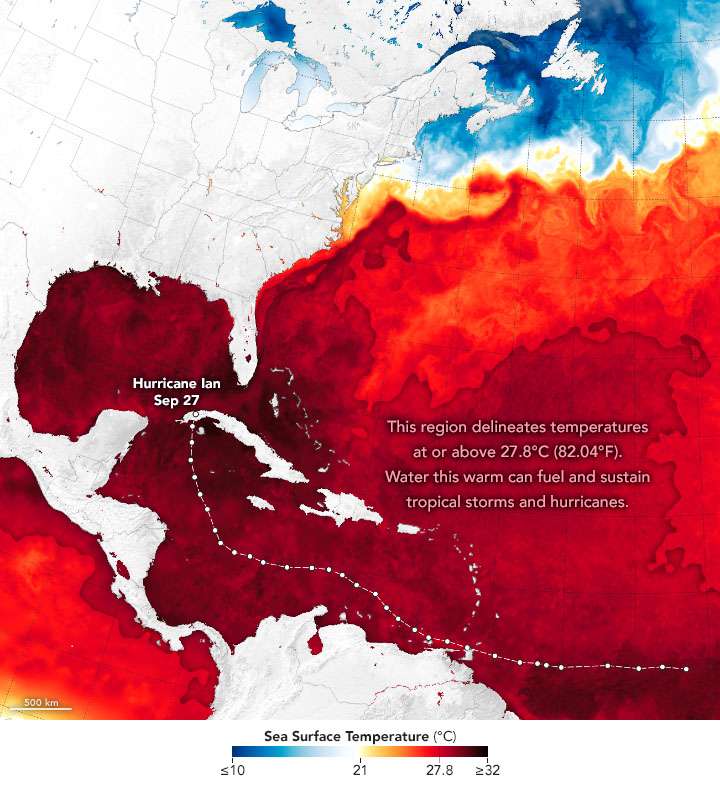

“The biggest one is the temperature of the water,” said Dr. Linda Ivany, a paleontologist who studies evolution and climate change, “The warmer it gets, the more energy the storm will have, so the bigger the storm is gonna be.”

Both Ian and Fiona had abnormal characteristics that illustrate this trend towards mounting destructiveness. Hurricane Ian intensified more rapidly than most hurricanes are known to do, and Fiona made it further north before finally subsiding.

“You can see houses that have been totaled, you can see boats that have been flipped over, cars that have been flipped over, and those have been very striking images,” said Florida Governor Ron DeSantis in a press release on Thursday, “But as the storm has moved through the state it has caused a lot of problems with really historic flooding in parts of central Florida and into northeast Florida.”

So while climate change may not be increasing the frequency of hurricanes, it is creating conditions that breed stronger and more destructive storms like those the U.S. received in September.

“In the case of Ian, there are warmer temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico,” Battacharya said, “As we move towards a warmer world, we will see stronger intensities of storms, and this is because those ingredients are likely to respond directly to greenhouse gasses. For instance, ocean surface temperatures are likely to warm more as a result of greenhouse gasses, making it more likely that any given storm will intensify rapidly like we saw this week.”

She says that these conditions have been accruing since the 1970s, and they can be seen across the globe.

“Yes there’s been a lot of change over the history of the planet,” Ivany said, “But it is very clearly demonstrated now that what’s been happening over the last 50 to 100 years is well outside the scope of what we see in the natural range of variation that the planet experiences.”

The conditions differ based on region, but all signs point towards the same reality.

“In our global models, which are pretty reliable, we see increases in potential intensity in future storms,” Battacharya said, “So that doesn’t mean more storms necessarily, but it does mean a greater likelihood that the storms we do have will be more intense.”

It is true that both hurricane season and the ebb and flow of Earth’s temperature are both natural processes. The issues caused by global warming and human development, however, cause these phenomena to be cause for concern.

“There’s always been hurricanes and there’s always been local damage associated with storm systems that come through and coastal settings,” Ivany said, “I think the problem that we have now is that there are coastal ecosystems being affected by so many different things and they’re all kind of interrelated.”

While it may be true that hurricane season produces more hurricanes, and the Earth heats and cools naturally, it is the strength of the storms due to human-induced global warming coupled with the weakening of ecosystems hit by such storms that are causing the increased destruction.

“It’s akin to being like ‘well of course it’s snowing in winter,’” Battacharya explained, “We do know there’s a seasonality to these things, but how much snow? What’s the distribution of snow? Does that snow actually impact human infrastructure? Those types of details are definitely changing even though, yes, there is such a thing as hurricane season.”

And not only are there human lives and infrastructure to worry about, but the resiliency of the ecosystems hit with such storms.

“The activities that humans have been doing of late have affected coastal ecosystems in a number of different ways, each one of which has its own independent effect,” Ivany said, “But the amalgam of them is much more compounded, and that gets even more magnified when you start to see these really big storms come.”

Wildlife that would normally act as protection against the brutal winds and rain is being destroyed. This, in combination with the increasing intensity of storms, decreases the ability for such areas to recover properly.

“As we cut down those forests, we sort of lost the ability of these coastal systems to buffer against the worst storm surges,” Battacharya said, “And storms are also getting more intense, so both those effects make these storm surges worse.”

Rebuilding and protecting such buffers is a way in which scientists believe we can guard against storms like Ian and Fiona.

“We can actually use conservation to try to improve our resilience,” Battacharya said, “It looks like preserving mangrove forests and coastal systems and not developing right up to the coast in all situations would buffer against the worst storm surges.”