GENEVA, N.Y. – In the humid rooms of industrial-sized greenhouses on the outskirts of Geneva live hundreds of hemp plants of more than 60 varieties, a large part of Cornell University’s hemp breeding and genetics program.

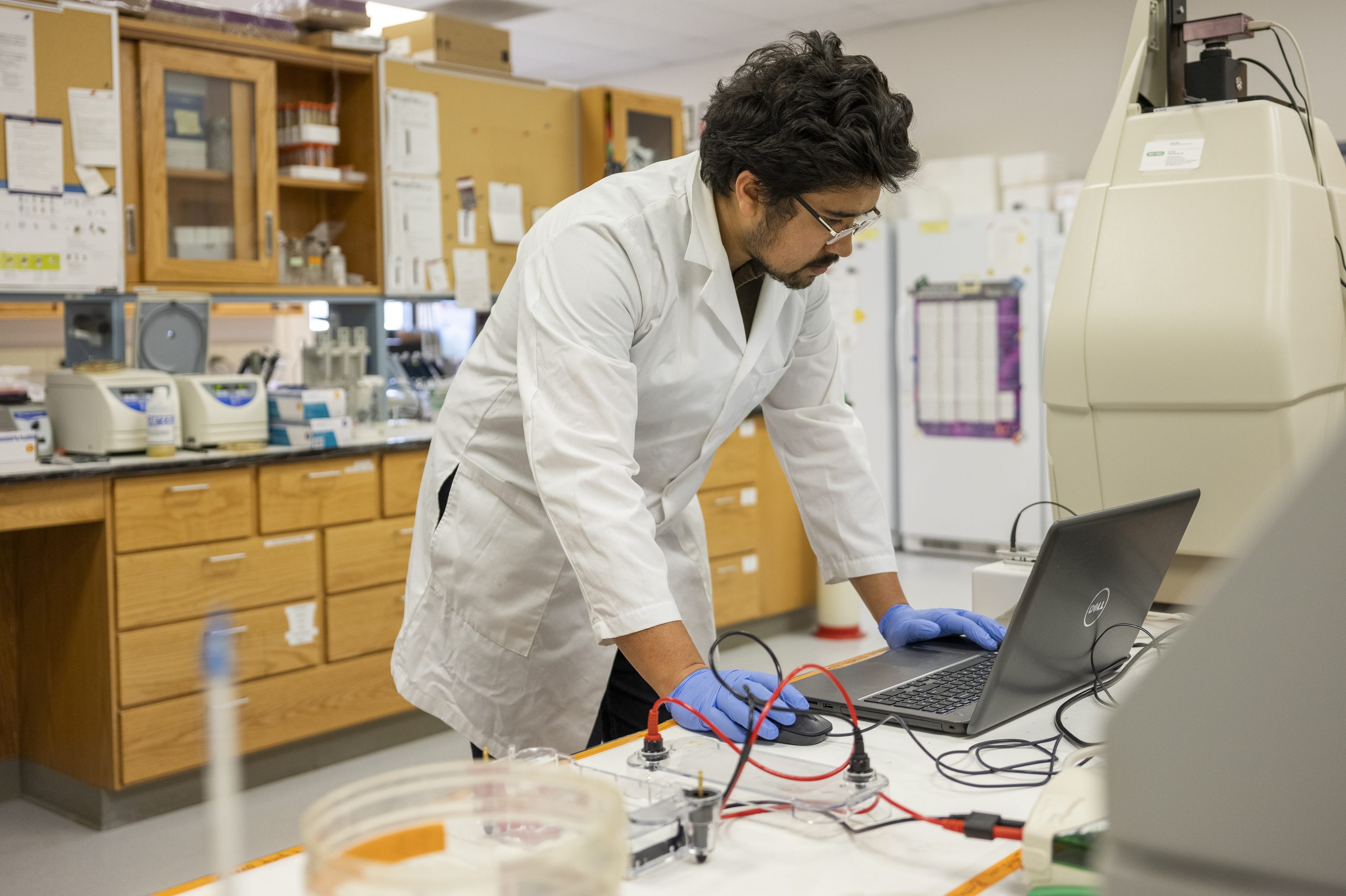

At Surge Laboratory, a short walk from the greenhouses, doctoral student Jacob Toth preps several test tubes for analysis. Their orange-hued broth contains genes responsible for making cannabinoids, the 100-plus chemicals found in the cannabis plant.

In one particular test tube, Toth has an enzyme that usually makes CBC (cannabichromene) but that he thinks is mutated to now make the psychoactive cannabinoid THC.

Through these genetic tests, Toth hopes to learn more about that small percentage of difference between the enzymes that make THC, CBD, and CBC, and what might be done to convert one into the other.

Toth’s tests are just one part of the Cornell Hemp program, which was backed by almost $4 million from New York State after the crop was legalized for research in 2014.

Cornell Hemp’s team of 30 researchers face pressure to develop hemp varieties that will advance New York in the crop’s budding national market, which began three years ago under the 2018 Farm Bill. But Cornell’s researchers walk a thin line of legality and are restricted in scope by federal regulations governing the psychoactive chemical THC.