Six months after Everson’s deaccession, here’s what the museum has done

Here's what the Everson has done with the Pollock funds

After much anticipation, the Everson museum revealed its first set of acquisitions following the deaccessioning of a Jackson Pollock. The seven new works are to contribute to the goal of furthering collection diversity.

The fall of 2020 saw the Everson announce, and then, sell Jackson Pollock’s Red Composition, 1946 for a cool $12 million. The two ethical governing bodies for museums, the American Alliance of Museums and Association of Art Museum Directors, have always allowed the funds from deaccession to be used for museum upkeep as well as new works. Due to COVID-19 the AAMD has temporarily loosed its restrictions and allowed those funds to be used for the “direct care of the collection”— a phrase that has been the source of much debate for the past year.

The Everson said proceeds would be used to diversify their permanent collection, as well as fund various conservation and collection storage projects. Unsurprisingly, the announcement and the subsequent sale were met with heated debate.

Deaccessioning — that is removing an item from a museum’s listed holdings in order to sell it — is a contentious topic at the moment. Museums like the Everson, the Brooklyn Museum, and The Baltimore Museum of Art find themselves at the center of a debate given their decisions to deaccession works by blue-chip artists.

Andrew Saluti, the program coordinator of the Museum Studies program at Syracuse University, defended their decision. “Deaccessioning is a very normal collections management process, museums do it every year. You’re going through and making sure that your collection reflects the mission, making sure the objects can be maintained,” said Saluti.

This sentiment was echoed by Christine Anagnos, the executive director of the AAMD. “What is significant about the discussion at this moment is the recognition that these collection building processes have still been too narrowly focused around works made by white artists generally and white men specifically,” she said.

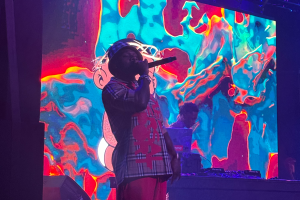

Only three months after the sale, the Everson announced the first round of these new acquisitions. The seven works include Shinique Smith’s Bale Variant No. 0021, Courtney Leonard’s Breach #2, and Ellen Lesperance’s Black Gloves Gods Eyes.

Also included are two quilts by Syracuse-based artist Ellen Blalock.

“To me, it’s a perfect acquisition,” said Saluti. “We have a huge history of the arts and crafts movement here in upstate New York.”

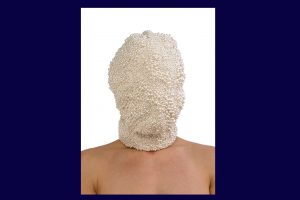

Blalock is not the only local artist featured. Sharif Bey’s Protest Shield #2 will also join the collection, an addition that helps create ties to the community and cement Everson’s status as a local museum.

“Artists are an important part of our community,” said Everson curator Steffi Chappell. “We do feel having local artists in our collection helps deepen our connection with the community which is something we always strive to do.”

There is no question that this round of acquisitions is a step in the right direction for Everson’s goal of diversity, but there is always room to improve. Saluti would like to see more contemporary indigenous artists featured.

Kristin Sheehan, director of communications for the Everson, explained that the funds from the Pollock sale will go into a trust where they will generate between $450 and 500k each year. The division of how those funds are spent each year between acquisitions versus direct care will differ.

The care needs of the museum for this year include the building of a new library, construction on which has resumed after the COVID-19 pandemic had forced a pause, and conservation on the Henry Moore sculpture featured on the front podium. Sheehan imagines that this project will begin in the Spring of 2022.

The Everson plans to include its new works in an upcoming exhibition entitled “Who What When Where” that is set to open later this month. After this Chappell says that they will continue to be used in future exhibitions and education programming. Sharif Bey is set to have a solo exhibition in 2022 and his piece may be featured therein.

Despite the seeming resolution of the Everson debate, the conversation around deaccessioning is not set to leave Syracuse anytime soon. Syracuse University’s Symposium, entitled “Deaccessioning After 2020,” will run from March 17 – 19 and is set to examine this debate from a wide variety of angles.

“Communities change, museums change, missions change and if we hold to this incredibly strict definition of what a permanent collection is, how can museums evolve to really support the communities they serve?” said Saluti, who is also involved with this Symposium.

It’s not a local issue. The discussion of deaccessioning is permeating the art world at large and causing a reexamination and reevaluation of the idea of a static artistic cannon.

“It is important to recognize that even the idea of an artistic cannon has not been historically as static as we sometimes think,” said Anagnos.

“The Cannon, in terms of the museum collection, is certainly in flux, we’re at a paradigm shift right now,” said Saluti.