Kevin Richardson talks justice, discrimination and love for the Orange

Kevin Richardson talks justice, discrimination and love for the Orange

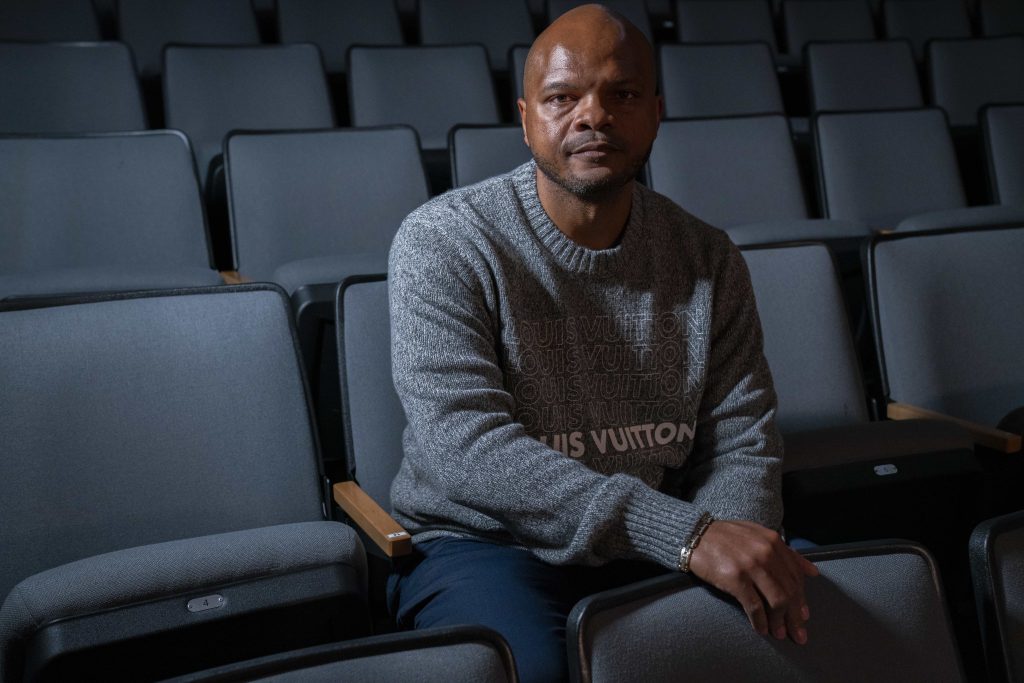

A member of one of the nation’s most notorious wrongful conviction cases three decades ago told a Syracuse University audience Monday that rampant racial discrimination persists in what he calls the criminal “injustice” system.

Kevin Richardson, who at age 14 was among the Central Park Five wrongly convicted of a brutal attack of a Central Park jogger in 1989, talked about the problems and issues he faced in the highly publicized criminal case that sent him to jail for more than 5 years before DNA evidence helped exonerate he and his four “brothers.” The case has received much attention this year in part with the highly acclaimed Netflix series, When They See Us, and the group is now often called The Exonerated Five.

Richardson, who dreamed of attending SU as a child, shared with the near-capacity Goldstein Auditorium crowd his traumatic experience of being imprisoned for years for a horrific crime he did not commit. The 44-year-old New York City native now works with the Innocence Project, focusing on the use of DNA in exonerating innocent incarcerated individuals; many of whom are black or brown.

“The system is built to let you lose hope,” Richardson said.

After being arrested in 1989, Richardson was held for more than a day without food, water or supervision. His confession to the crime was coerced, after hours of relentless questioning and manipulation on the part of the police. At the Innocence Project, he works to legally require interrogations of youths accused of crimes to be filmed, so that coerced confessions of vulnerable minors can be detected and proven.

“They thought that they had me, they thought that I was defeated,” Richardson said, referring to his case’s prosecutors. “You have to keep exercising your rights, and exercising your mind, body and soul.”

Syracuse University law professor Paula Johnson, who joined Richardson and Candice Carnage of The Bronx Defenders on stage, said she has always been offended by the inability of the legal system to admit its error when people are exonerated. Neither the state nor the city of New York ever apologized for wrongly imprisoning five young black men.

“So much could be addressed if we could all acknowledge the harm that we commit on every level: individual, institutional, societal,” Johnson said. “And that might be a place to start to have these necessary conversations.”

Carnage said her Bronx-based organization aims to help minorities who are ensnared by the legal system. With the Bronx being one of the most over-policed communities in the country, Carnage said that 98 percent of its clients are black and brown.

“There is no escaping. Once you’re caught up in the system, you’re in the system forever,” Carnage said. “Unfortunately, we are just a Band-Aid for the overall problems we have in this society.”

Carnage explained that systemic racism has always existed in the U.S. and that it manifests itself in different ways over time.

“We have moved from slavery to over-incarceration. I’m not sure what the next fad will be,” Carnage said. “But I’m pretty sure it’s going to be them standing on our necks like they have been for the last 400 years.”

One woman in the audience spoke to Richardson about her brother. She said that her parents never forewarned them of the racial discrimination in the U.S. that they would likely face as African Americans because they were immigrants and came here unaware of the racism in this country. She told Richardson that his story had a particularly profound impact on her, as she has a 17-year-old brother. He currently attends a predominantly white school, and she said she was worried that he doesn’t understand why, as a black student, he’s different.

“You’re not like every other student, you’re not like every other person. You’re black,” the woman said of her brother. “You’re (a) tall, dark-skinned, six-foot black boy — and they will hurt you.”

After a tearful pause, she expressed her fear for him as he navigates a society in which there is great underlying racism.

In the aftermath of experiencing a racial injustice on a national scale, a significant part of the discussion focused on healing, moving forward, and continuing to fight against such injustices. A part of the devastation remains with the victims, Richardson said, but he works every day to keep going and thrive despite what happened to him.

At the beginning of the talk, Richardson reminisced on Syracuse University players he admired as a child. He also reflected on his passion for music and his aspirations to play the trumpet at Syracuse University.

“I was always fascinated with the campus. I always wanted to wear that orange. You know, it was the Orangemen,” Richardson said. “So when I received a call that Syracuse wanted to invite me here, I felt 14 all over again.”

Richardson said he didn’t think he’d be alive to ever see Syracuse University after he was imprisoned.

“I am truly grateful to step two feet on the ground at Syracuse.”