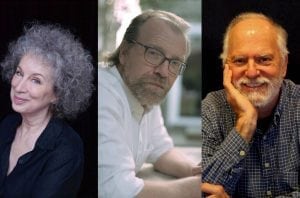

George Saunders opens the 2018 University Lectures series

George Saunders is a sucker for getting along

George Saunders has written nine books, appeared on the Colbert Show, sold a script to Ben Stiller, received an MFA, and won multiple awards and recognitions including a spot on the New York Times Bestsellers list. But as attendees at his Thursday night talk in Hendricks Chapel learned, he is also a man who jokes about bad poetry and confesses about his insecurities.

Saunders, a professor in the creative writing department at Syracuse University for more than 20 years, won the 2017 Man Booker Prize for his debut novel Lincoln in the Bardo. His 2013 book of short stories, Tenth of December, earned a place on the New York Times’ 10 Best Books of the year.

Thursday night, he spoke on stage with fellow creative writing professor Jonathan Dee to kick off the 2018 University Lectures series.

“You’re sort of a ‘hometown boy makes good’ story,” Dee said to Saunders, “though you’re not actually from here. It took you a while to get here.”

Saunders originally grew up in Chicago where he later worked as a roofer. He went to engineering school at the Colorado School of Mines and worked for a time in Texas as a groundskeeper, all before earning an MFA in creative writing from Syracuse.

“I didn’t publish my first book until 38. I’m from a working-class background. I’m a working-class writer,” said Saunders, who first heard about MFA programs through a People magazine article. “There’s a phenomenon that when things go well for you, you can start to think that nothing else is going wrong in the world.”

But it’s important, said Saunders, to remember that just because you’re having a good week, that doesn’t eradicate your past or the problems of others. Remembering that there is still pain in the world is a compassion you need to have, he said, and it was this mindset that influenced his reporting on Trump in the days before the 2016 election.

While writing for the New Yorker, Saunders attended a series of Trump rallies even before the president’s official candidacy was announced. Through interacting with people at these rallies who both loved and hated what he wrote, his faith in the power of kindness was emboldened.

“You can be firm on your side and still keep your heart open and love thy enemy,” Saunders said. “We just have to stick to the core values of compassion and empathy.”

Compassion and empathy remained constant themes throughout Saunders’ talk, whether he was referring to angry commenters on the internet, students or even his stories themselves.

As a professor, Saunders talked about accepting students into the small, six-person program and the process of helping them grow. “There is the pleasure of remembering that talent is eternal in this world,” he said. “If the writing stuff goes away, and it will, the fact remains that you get to take a young person and bring out their talents.”

Saunders spoke about how Syracuse immediately felt like a warm, welcoming home to him and how he tries to make his own students feel the same way. He also talked about the importance of reading to the cultivation of future writers, recalling a nun who encouraged him to read in third grade and saying that much of writing comes intuitively after one’s brain has learned tricks from reading.

“Even if you’re half-baked at the moment, there’s a full human being in you that really wants to come out,” said Saunders, encouraging students in the audience to find someone who believes in them as he clearly does in his own students.

Saunders had a habit of referring to stories, projects and pieces of writing as if they were people with feelings to which he needed to be empathetic. When asked by audience members and Dee about his process of writing Lincoln in the Bardo and other works, he talked about listening to where a story is going, asking it why it’s not moving along properly, and remembering to always respect the reader. By miming several conversations with stories he’s written, he made it clear that his stories talk to him in a way that allows him to sit down at his desk without solid themes or outlines and work with simple images and ideas instead.

“If it’s fun, and I don’t know where it’s going. That’s the gold standard,” he said. “Ultimately, you’re the one that has to make the call when it’s ready.”

Before heading to the lobby to sign books for guests, he enthusiastically thanked the audience for “twenty beautiful years of teaching.” Though Saunders had a propensity for self-deprecating jokes about C+ grades in college and picking up dog poop just like everyone else, the waiting area was packed with people buying his books off a display table and waiting for autographs.

A young man, who finally reached the signing table after waiting at the end of a long line, asked Saunders to make the signature out to his English teacher who had once given him one of Saunders’ books. Saunders wrote a personal note thanking her for teaching his work and, in red sharpie, made sure to draw some hearts after the message for good measure.

“Compassion and empathy,” said Saunders. “I’m kind of a sucker for the idea that people can get along.”