Why climate issues are human rights issues

Why climate issues are human rights issues

The unequal impact of climate issues felt by communities across the country fuels an urgent need for environmental justice.

Growing up in the Onondaga Nation, Sophia Powless never spent her summer days by the lake near her home. Instead, while her family drove past Onondaga Lake, Powless recalls plugging her nose to avoid the pungent stench of the lake’s toxins.

Onondaga Lake is located in Central New York along the edge of the City of Syracuse, notoriously known for being the most polluted lake in America. In the early 1900s, chemical manufacturers dumped sewage and industrial waste in the lake. For decades, the Allied Chemical Company, a chemical company and predecessor to Honeywell, discharged approximately 165,000 pounds of mercury into Onondaga Lake. Methylmercury, a type of mercury found in aquatic systems, is among the most poisonous chemicals found in the lake.

“When I was younger, I heard a lot of stories about how Onondaga Creek and the lake were so full of fish that you could walk across it on their backs,” Powless said. “It hurt me to see such bountiful diversity be completely eradicated within a lifetime.”

In 1970, the U.S. Attorney General sued the Allied Company, and the lake was later declared a Superfund site – a location contaminated by hazardous waste designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for management and cleanup. Despite more than $1 billion spent on cleaning up the lake, Onondaga Lake remains a Superfund site today, with toxins still present.

Centuries ago, the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk Nations united together on the shores of Onondaga Lake. At the lake’s coast, the warring nations laid down their arms made peace, and formed the Haudenosaunee Confederacy — the first representative democracy in the West. The lake became a sacred place, one that must be cared for and respected.

The pollution and decades-long neglect of the lake have prevented the people of the Onondaga Nation from carrying out their sacred duty to respect and give thanks to the environment. Like many Indigenous communities, the environment plays an indistinguishable role in the Onondaga Nation’s culture.

Whatwehni:neh Freida Jacques, Onondaga Turtle Clan Mother and educator, explained that the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people begin all meetings and ceremonies with a traditional Thanksgiving Address, where all parts of the natural world are given thanks for sustaining life.

“If you do this [give thanks] all your life, you’ll respect life. When you see things growing, you’ll respect that life, too,” she said. “If you thought of, and thanked, the Waters all your life, you would know how important they are.”

Sophia Powless, a member of the Onondaga Nation Wolf clan and indigenous climate educator, said that growing up near a Superfund site made her acutely aware of issues like fracking, land rights and pollution from a young age.

When Powless learned that non-Indigenous people did not have the same understanding of the environment as she did, the Columbia Climate School graduate began her climate journey.

“My journey has been trying to guide people upon a path of where they can realize how much of a deep connection that they might have to the environment, or to experience that connection with our Mother Earth,” Powless said.

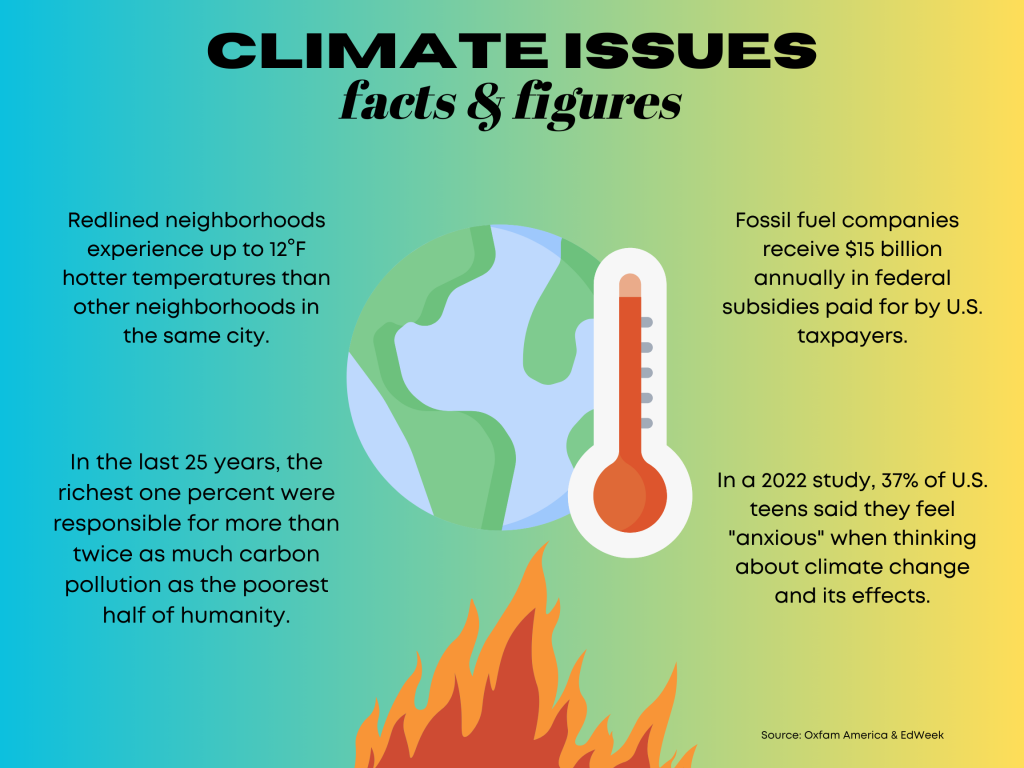

For people of all backgrounds and identities, climate change and environmental issues are among their list of most pressing issues. Young people are especially affected. In 2021, The Lancet found that about 70% of people ages 16–25 are extremely worried or very worried about the climate, and climate-related anxiety increases for people in developing countries.

This makes sense given that as of 2021, over 85% of the world’s land mass experienced the devastating effects of global warming, including rising sea levels, more frequent and intense natural disasters, and changing weather patterns. Today, nearly 50% of U.S. counties face an environmental disaster each year. A century ago, that number was only 20%.

Since Greta Thunberg went viral in 2018 for her solo strike at the Swedish Parliament, over seven million young people participated in climate protests in more than 140 countries around the world. Yet, studies how many young adults struggle with feelings of anger, hopelessness, guilt, and sadness relating to climate change.

Victor Ramirez, a Princeton University civil and environmental engineering student from South Florida, said that even after living through over 20 summers in Miami, each summer grows more unbearable and unpredictable.

“If you go outside in the summer without drinking water, you’re going to get extremely dehydrated or put yourself at risk for heatstroke,” Ramirez said. “When I travel home and experience the heat, it hits me. I’ve gotten more worried about the summers over time.”

Science also supports his observation. In fact, The Fourth National Climate Assessment released in November 2018, identified extreme heat among the most serious threats to human health in urban areas across the United States. Similarly, a study from the Union of Concerned Scientists found that Miami-Dade County is one of the most at-risk areas in the United States for heat-related illnesses and deaths. The report states that between the years 2036 and 2065, the county could experience an average of 98 days per year with a heat index above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, which is considered very dangerous for outdoor activity.

While Ramirez has always been aware of socioeconomic struggles in his community, it wasn’t until he reached college that he learned how climate change widens preexisting socioeconomic gaps.

“When I learned about housing policies in my classes, like redlining, I thought about Miami-Dade County,” Ramirez said. “People who work in the sun, people who live without proper energy through the summers, people without resources when hurricanes hit.”

Redlining is a practice that involves the systematic denial of loans, insurance, and other financial services to residents of specific neighborhoods based on their racial or ethnic makeup. This practice historically led to the long-term concentration of poverty, reduced access to quality housing and healthcare, and increased exposure to environmental hazards for residents of redlined neighborhoods.

In Miami-Dade County, redlining contributed to the unequal impact of heat-related issues on low-income communities and communities of color. A 2021 report from the National Library of Medicine emphasized how hot conditions and stress caused by heat take lives, increase negative pregnancy outcomes and worsen mental health.

“It just makes you think how your community gets affected and will change by the time we reach our parents’ ages,” Ramirez said.

The 2021 medical report also notes that residents in lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color are particularly vulnerable to heat-related illnesses, as they are more likely to live in areas with less tree cover, less access to air conditioning, and less access to healthcare.

@blairimani Happy EarthDay! A reminder from me, @isxenvironmentalist, @mikaelaloach and @capybarasorganize to keep your climate activism intersectional in this #SmarterInSeconds on Environmental Racism 🌱🌍

There is a paradox of the human impact of climate issues on wealthy versus lower-income communities. Though wealthy people contribute a million times more greenhouse gas emissions than the poorest 90% of people, people of color and low-income families are more likely than white people to die of environmental causes.

The problems posed to excluded communities don’t stop at higher temperatures. According to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) study, these areas are also more likely to experience flooding and extreme heat — both exacerbated by climate change. In the United States, the cost of drought increased by 476% since 1980 while the cost of flooding has increased by 1,567% since 1980.

But Elizabeth Carter, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Syracuse University College of Engineering and Computer Science, emphasized that the largest “cost” of water-related climate issues is the human cost.

“More people are impacted globally by droughts and flooding than all other types of natural disasters combined,” Carter said.

In Carter’s research on the human impacts of hurricane and flood-related disasters, she found that historically racist policies contribute to longer timelines when trying to develop infrastructure solutions to climate issues.

“The data that we use to make decisions about infrastructure and how we’re going to repair infrastructure is biased along socioeconomic gradients. The biggest thing that we use is just property values,” Carter said. “If you take that into the context of the weighted history that we have around redlining, you see how that would be problematic and compound legacies of inequity.”

The harsh reality is that marginalized communities bear the brunt of the impacts of climate change, and deeply entrenched prejudice in our country’s systemic policies inhibits equitable resolutions.

And other experts agree. Samantha Montano, an assistant professor and author of Disasterology: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the Climate Crisis, said much of U.S. modern coastal management is “reactive” rather than “proactive.”

“The U.S. emergency management system was created for middle-class white people in the 1950s, and it has not changed that much since then in terms of policy,” Montano said during her presentation to the MIT Water Summit in 2021.

Robert Kopp, professor and director of the Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, said that sometimes, these issues amount to what is known as “climate gentrification” or post-disaster gentrification. This is when natural disasters create so much damage that people are either forced to relocate or rebuild their homes. The danger is that many people often do not have the luxury of relocating, or they simply don’t want to leave the homes they’ve known all their lives.

“Wealthy people have more resources to deal with shocks to their well-being,” Kopp said. “And so anything that causes more frequent shocks, like climate change, is going to exacerbate inequality.”

Where do we go from here?

Given the challenges highlighted by several experts, addressing historical prejudices and ensuring effective strategies are critical to tackling climate change’s impacts. While this may seem like an impossible task, Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist for The Nature Conservancy and author of the best-selling book Saving Us, points to a statistic: A Yale public opinion poll showed that more than 70% of Americans agree on a need to fight climate change. That same 70% also agreed it will harm plants, animals, and future generations.

Hayhoe’s advice is simple — the first step of climate action is to have a conversation about climate change.

@unclimatechange “Climate change is touching every part of our lives” – Climate Scientist @dr.katharine at #COP27 #ClimateAction

“We can’t give in to despair,” Hayhoe said. “We have to go out and look for the hope we need to inspire us to act — and that hope begins with a conversation, today.”

For Powless, the importance of conversation is also a teaching she grew up with, having learned it from her grandfather.

“He taught me the biggest thing that we need to have when we’re trying to talk to people who have a different side of an issue, is it’s all about respect,” Powless said.

When discussing climate change — an issue so inextricably intertwined with all aspects of life — Powless and Hayhoe both suggested that framing those conversations to focus on what truly matters can create momentum.

“I think that a lot of the stigma for talking about climate change is that it’s complex,” Powless said. “It is complex. But I think there are always ways that we can approach it, that can really connect with people.”

Through conversations, people overcome differences, acknowledge unique lived experiences, and get to the root of systemic issues. While many young people may assume that climate action requires contacting politicians or participating in protests, it can be even more simple.

Powless also encourages young people to embrace their creativity to share the many stories of climate change. As an artist, she’s in the process of developing a game about climate change called “Pathways.”

The premise of the game is that a player picks a card that reads a climate-related scenario. For example, “Should we burn down this forest to increase our furniture industry?” If a player responds according to environmental preservation and respect, they are able to spin and move their character forward.

“Gamification is so powerful in that, it’s interactive, it’s engaging, and even if not all of the prompts and scenarios, stick with the participant, some of them will,” Powless said.

There are other original questions that young people can ask themselves in combatting climate change. For instance, Rutgers’ Kopp encourages young adults to explore how their professional interests and educational paths intersect with environmental issues and climate change.

“Everything in the economy in our society has a connection to the climate crisis,” Kopp said. “So I think that’s a question to ask people to think about what they want to do with their lives: ‘How is my life’s work affected by the climate crisis?’”

Despite the depressing nature of climate change discussions, young people can understand how society’s actions today can empower the future and reclaim the past.

Powless suggested that a gratitude and mindfulness practice can help to combat some of the “climate anxiety” many of us feel today. One way she does this is through the “seventh-generation principle,” which is a common practice in the Onondaga Nation. The seventh-generation principle prompts an individual to consider how their present actions today will affect the next seven generations after them.

“It takes a lot of mindfulness and patience to really think about the actions that we’re doing, it’s not just for us,” Powless said. “There are going to be people after us.”

When focusing too heavily on the large-scale of these issues and collective climate anxiety, Powless said it’s easy to feel paralyzed or unsure how to move forward. But by focusing on the present moment and our current actions, we can recognize our power and create positive impacts for generations to come.

“It’s going beyond just seeing the inherent value of the natural resources,” she said. “Do you not want your younger cousins, your younger siblings, to experience the same beauty of the planet as you are seeing it right now?”