Editorial: Meet Syracuse’s resident autograph hound

Editorial: Meet Syracuse’s resident autograph hound

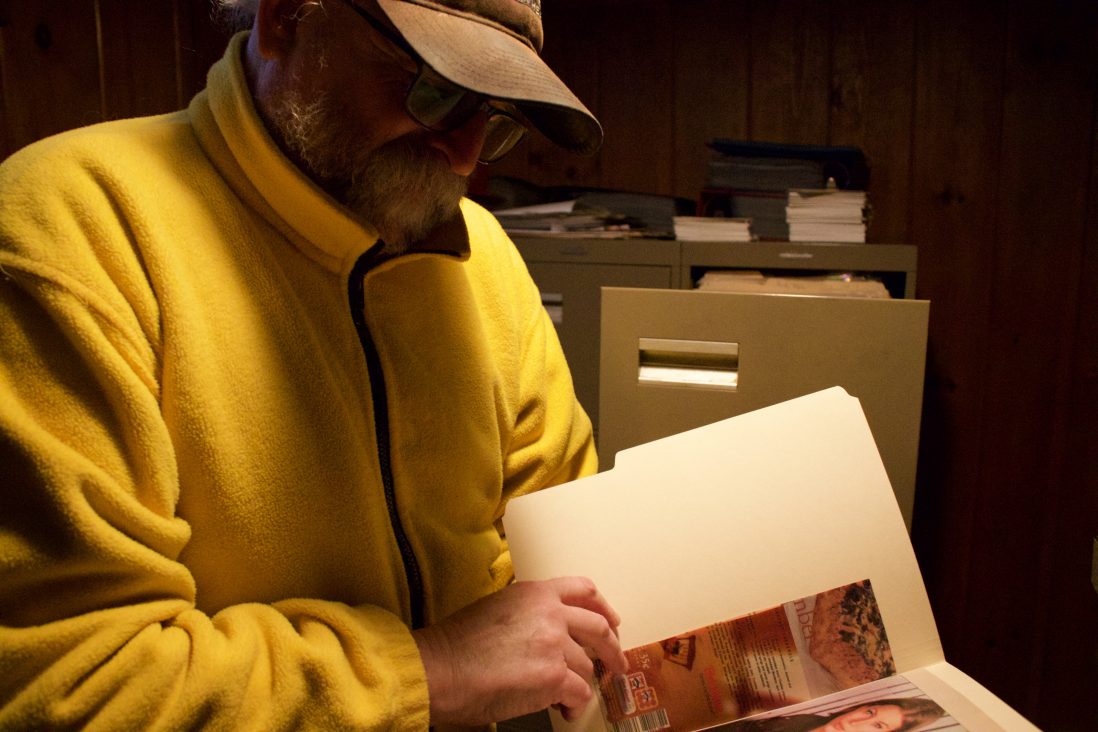

The stairs to 67-year-old Richard Block’s basement are steep and narrow. He shuffles down the steps and into a small, dim room crowded with stacks of papers, folders and binders resting on the cold, gray linoleum floor. Block walks directly to the back-left corner of the room and stands in front of two gray filing cabinets, almost as tall as he is.

“Who’s your favorite celebrity?” Block asked. “I’ll pull out their folder.”

Besides Block’s massive autograph collection, he also keeps tabs on celebrities he deems important, like a doctor keeping tabs on all their patients. His filing cabinets are full of folders, each folder adorned with a name of a singer, songwriter, actor, politician or public figure. Every folder holds a variety of newspaper clippings and photos of the celebrity that Block has collected over the years.

He pulls on Justin Bieber’s folder, and though Block said that no, he isn’t a fan, he knows that Bieber has reached a level of fame worthy of a folder. When the chance arises to possibly secure an autograph from one of these stars, or perhaps chat with them for a few minutes, Block said he wants to be prepared. He makes copies of all the articles and news clippings to give to them, “to butter them up,” he said. Usually they’re very excited that someone spent the time following their career, and that it’s all there in black and white.

If there’s a Syracuse University speaker event on campus, Block is in attendance. He arrives ten minutes early, in his typical uniform; a bright yellow fleece, baggy gray sweatpants and a navy blue and orange SU beanie.

He hits up the snack table first, usually loaded up with Varsity pizza or Insomnia cookies, then he takes his seat in the front row. His wispy white beard hangs over his lips and his transition lenses fade from dark to light as he settles in to listen.

“I remember him coming to events back 25 years ago or so, when I was a student working for the Daily Orange,” said the Director of the Tully Center for Free Speech, Roy Gutterman, who is also an associate professor in the Magazine, News and Digital Journalism Department.

Block makes his way to SU at the beginning of each week to investigate what upcoming speakers are coming to campus, and then makes his schedule around the events. Former Newhouse Dean, David Rubin, said he was apprehensive about Block at first.

“You never know if these people are here to agitate the speaker or cause trouble,” said the former dean.

But week after week, year after year, Block showed up for practically every Newhouse Speaks event. He sits quietly in his seat and as soon as the speaker has finished, he’s the first to leap out of his seat and collect their autograph. After a few times sitting in the Hergenhan Auditorium observing Block, Rubin realized he had nothing to worry about.

“He’s a very pleasant person, he’s just taking advantage of what is basically a free college experience,” said Rubin.

While simply attending SU speaker events could give the audience quite the education, more than 50 years ago, Block was a Newhouse student himself. His career as a reporter, and lifelong passion for SU news and campus life, began when he enrolled as a broadcast journalism major in 1971. Block wasted no time, almost as soon as he arrived on campus, he started working for WAER.

“I never interviewed for a spot, I just came in one day and said I wanted to be on-air, and that was that,” he said.

Today, WAER is a professional Syracuse news outlet where Newhouse students can develop their reporting skills. But back in the day, it was a little news station operating out of a Quonset hut, made of light-weight steel with a semi-circle roof. The Quonset huts were built for veterans returning from World War II as a cheap housing option. Leftover from 1946 when SU built nine hundred Quonset huts to accommodate the growing number of veterans coming to campus.

Block said back then, WAER was a free for all.

“I don’t mean we ran around without pants on and swore on the air,” he recounted with a smile, “but if you were a disc jockey and you wanted to play a full record, no one was going to stop you.”

Block took on the unofficial role as news director at the station, reporting on what was going on on-campus and conducting live interviews with notable figures who came to Central New York.

In the Quonset hut at the bottom of Mount Olympus, with the rubbery, soundproof walls – that, according to Block, could be punched and would bounce right back – he built his chops as an interviewer.

He invited campus speakers to do live interviews, and, when they showed up, he was able to interrupt regular programming and broadcast their on-air conversation for up to an hour. In their little shack of a radio station, Block interviewed celebrities — Jerry Lee Lewis, performer Tiny Tim, and consumer-activist Ralph Nader.

After graduating from Newhouse in 1974, Block’s first job was as glorious as any recent college graduate can imagine.

He became the news director at a cable TV news station, broadcasting out of the garage of a motel in Potsdam, New York. The owner of the Chalet Motel decided to convert the motel’s garage into a broadcasting station. But he didn’t have the right type of permits to make this operation successful—or legal, for that matter. The job was about as DIY as it gets, Block says.

“We didn’t have anyone to do graphics,” he said, “so we would just hold up cards with transitions on them into the camera.”

He likened the production value to about a 5th theater production. Needless to say, the station didn’t last long, and Block was out on the search for another reporting job after only a few months.

Block jumped from station to station in Central New York. He spent time working in Geneva, Oswego and Auburn, but he always wanted to return to Syracuse.

“I was raised here, I grew up here, I know Syracuse,” said Block, who lives in his old childhood home, a two-story bungalow off of Salt Springs Road.

Block moved home several years ago to take care of his aging mother, Gertrude Block, who passed away in 2017. The house happens to be across the street from his old middle school, now Nottingham High School, and only a five minute drive from SU.

But one thing that has changed in the four decades since Block was a kid religiously watching the News Bowl on TV Saturday mornings, is his autograph collection, which he says “has taken over the house.” Block never married, doesn’t have any kids and is a self-identified loner.

But his autograph collection, which he calls “just a hobby,” keeps him busy.

The Newhouse alumnus and former reporter has been collecting signatures of famous, and not-so-famous, celebrities for more than 40 years. It started when Block interviewed Duke Ellington in 1971 for WAER. Block, an avid jazz fan, considers Ellington “the greatest jazz musician and composer of all time,” but the interview didn’t go as well as he would’ve liked.

“It was a terrible interview, really just awful,” said Block.

He attributed the poor conversation to Ellington being sick at the time. So, Block packed up his voice recorder and bid Ellington farewell.

But as Block was walking away, Ellington called after him, “Oh, so you don’t you want my autograph?”

Block was taken aback, all he had with him was a scrap of paper that he found in his jacket pocket, but Ellington signed it anyway.

40 years later, Block has upgraded from scraps of paper to posters and glossy photographs. Next to the filing cabinet, in the left-hand corner of the dark, cluttered basement, stands an old wooden bar, though it doesn’t seem like it has been used for Moscow Mules and Mai Tais in quite some time. Block, who rarely drinks, besides the occasional glass of Manischewitz wine, utilizes the bar for his many huge, plastic, metal-ringed binders of autographs.

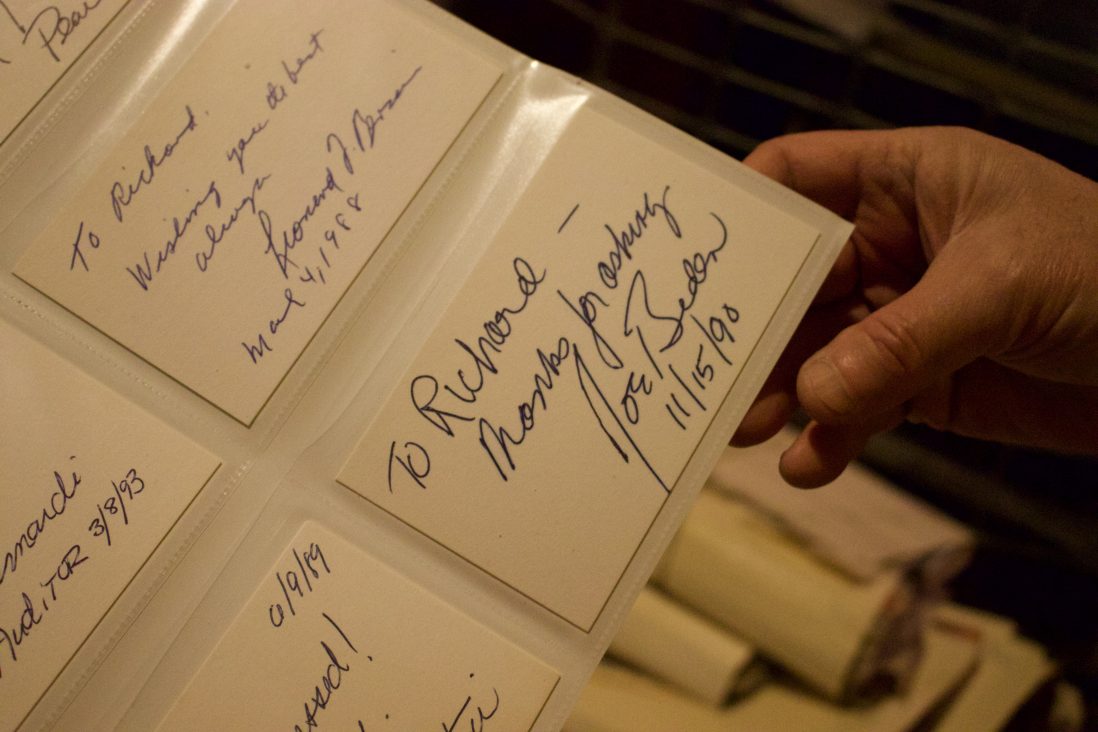

The binders are color-coded — red is for musical artists, blue for politicians and public officials and black for actors and actresses. There’s at least six of each color weighing down the already-sagging bar.

He hoists one of the huge red binders into his arms and treks through the heaps of papers on the ground and back upstairs.

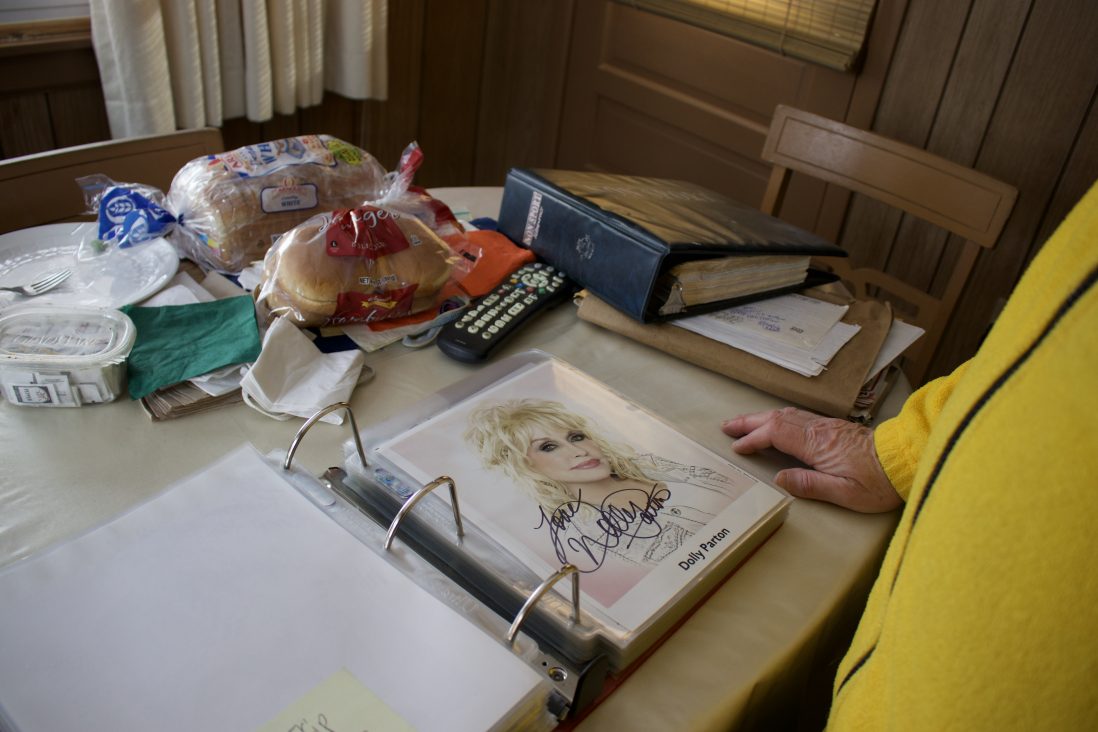

Block’s kitchen doesn’t seem like it’s been changed since the ‘50s, with wood paneled walls and white floors. The beige plastic tablecloth covers the kitchen table, which Block drops the binder onto. It lands with a loud thump, that rattles the two loaves of white bread and remote lying idly on the table. He opens up the binder and goes through each page, explaining who the person is and how he obtained their signature.

One of Block’s favorite autographs in his collection is from former president Bill Clinton. Block acquired his autograph when Clinton served as the governor of Arkansas. The former mayor of Syracuse, Thomas Young, and his staff invited Block to the governor conference because they knew he was a collector and thought Clinton’s signature would be of value to Block. They were right, Block jumped at the opportunity. But they warned him not to take up too much of Clinton’s time.

So, when Block met the former president, he tried to be as efficient as possible, but according to Block, Clinton was “so friendly and so outgoing and kept trying to talk to me about my collection.” Mayor Young’s staff was eyeing their interaction and as much as Block kept trying to rush the former senator, Clinton kept trying to engage Block in conversation.

“I wanted to say, ‘God damn it, just sign the picture!’” said Block, but he bit his tongue.

Though Block is retired, his autograph collection, which is one of the largest in the Central New York region, is a full-time job.

It’s not always as simple as attending a campus event and grabbing the speaker before they exit the room. Block sends out at least 14 autograph requests every week. The names of which are scrawled on old envelopes and backs of receipts laying on his kitchen table. Block puts a picture of the celebrity and a pre-stamped self-addressed envelope, and he requests that they sign the picture and also include a second autographed picture if they can.

But Block’s Santa factory of autographs does have some outside help. Namely, from public relations manager Brian Abbott, at the Community Library of DeWitt and Jamesville. Once a month, Block meets with Abbott, and he helps Block by looking up addresses of celebrities or other notable figures so Block can send out his autograph requests. Since the library’s Who’s Who In America book is from 2013, and Block doesn’t own a smartphone or computer, Abbott is Block’s first line of attack for growing his collection.

He makes a point to identify the duplicates in the binder, because the person did in fact send two pictures back.

“The number of people who don’t respond is stunning,” Block said, while explaining how costly this past time can be. “All the self-addressed stamped envelopes really add up, and when they don’t respond, I also lose the picture of them that I sent.”

It may be simpler for Block to print out pictures of celebrities from a laptop, but Block doesn’t have any kind of technology besides a TV and a landline.

“I’m stubborn,” he said with a shrug. “I like what I like.”

While he was still reporting, he would first write out the story long-hand, type it up on his manual – not electric – typewriter, head down to Kinkos and fax the story to the publication. Block, who’s never even had a flip phone, says he’s “just gotten by without one.”

There’s one thing that technology can’t replace, though, and that’s heaps of autographs from stars like Dolly Parton and Joe Biden that make up more than 5,000 signed pictures and posters, not including his collection of autographs on 3X5 cards.

“There’s something about the blue,” said Block about the signatures in blue Sharpie, “it’s so…vibrant.”

These are the things Block notices, along with the fact that two of his autographs aren’t in alphabetical order, as we flip through one of his binders. He pauses to switch them to the correct pages. As we continue through the binder, there is a noticeable difference between the black and blue sharpie. The black fades into the picture, because many of the photos are black and white, and the signatures in black sharpie seem to lay flat on the page beside a smiling face.

But the blue, the blue is electric. It screams, “To Richard,” or “Best wishes, Richard.” He points out every signature written in blue marker, which matches the same shade of vibrant blue coating his freshly painted house – perhaps a reflection of his collection.