An icy breeze blows off the shores of Seneca Lake, rattling the glass panes of the Cornell University greenhouse in Geneva, a small city in the northern Finger Lakes about an hour west of Syracuse.

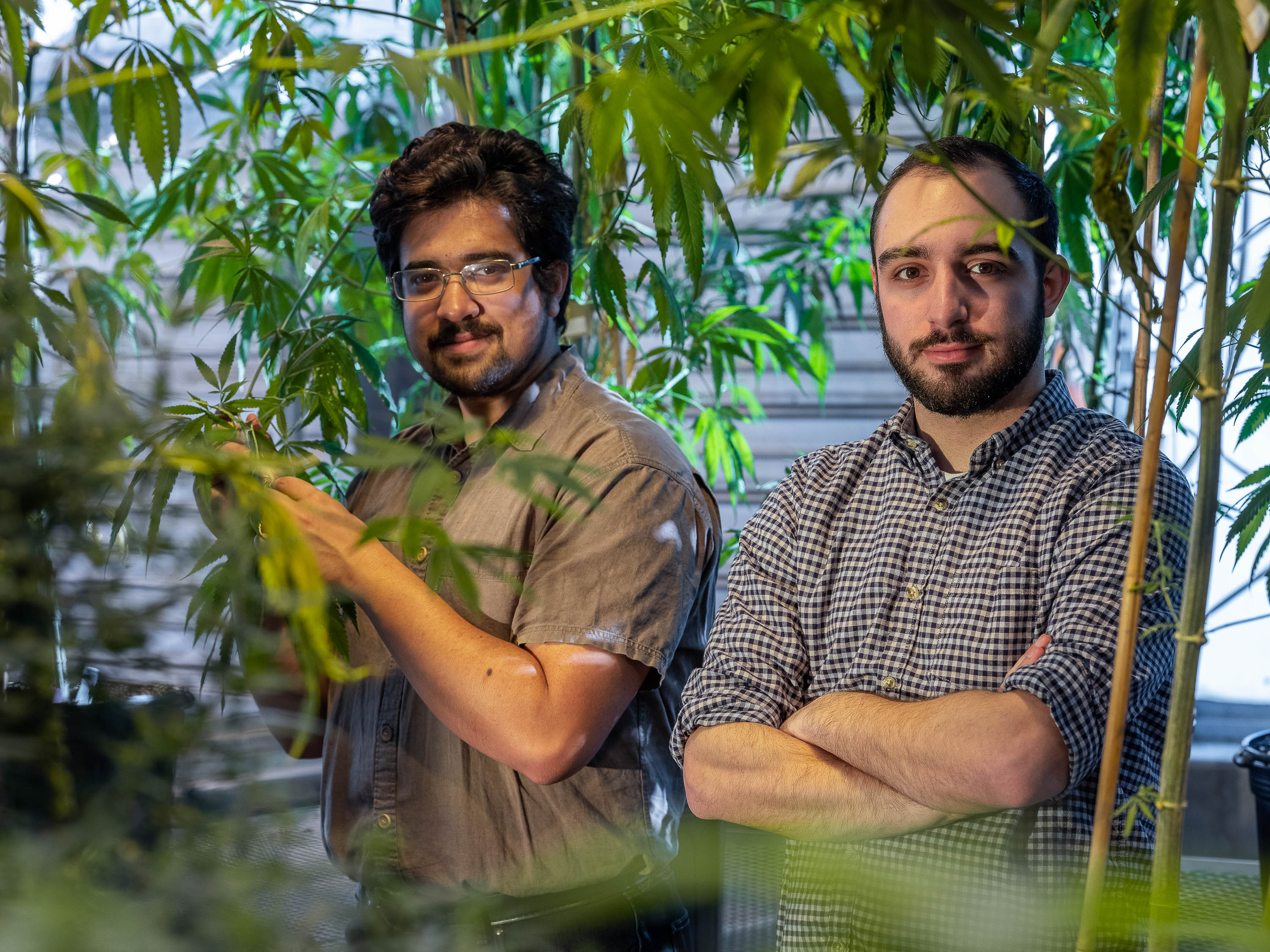

Inside the greenhouse — part of Cornell’s AgriTech satellite campus — it is warm and humid. Graduate student Jacob Toth walks down the center aisle of the greenhouse until he reaches a locked door, a “No Trespassing” sign posted beside it. He takes out his keys, unlocks the door, and steps into a scene unimaginable in New York state just a few years ago.

“This one we got from Oregon,” Toth says, approaching the first row of plants. He pinched an instantly recognizable five-pronged leaf between his fingers. “They said it was a good grain fiber variety.”

Inside this subsection of the greenhouse, Toth is growing hemp plants. Lots of hemp plants –– several rooms’ worth, in fact. At Cornell, Toth is part of a state-approved research project breeding hemp plants specialized to different products, from fiber to CBD oil to, perhaps one day, recreational marijuana.

Toth’s research encompasses another aspect of the budding hemp industry in New York: the marijuana supply chain.

For years in New York, the supply chain for pot has existed outside the legal realm, conducted through underground market distribution channels hidden from government regulators. Now, the decisions state lawmakers make as New York works toward legalization will help shape a new supply chain, dictating the price, quality and variety of marijuana sold in the state.