Review: Everson’s ‘Who What When Where’ exhibition seeks to be a space of reconciliation

Review: Everson's exhibition seeks to be a space for reconciliation

Grief, pride, harmony, self, violence and empowerment.

The Everson Museum’s newest exhibition, “Who What When Where,” offers a conglomerate of emotions. Based on the 1998 photo series of the same name by artist Carrie Mae Weems, the exhibit features a multitude of works connecting back to her original intention.

One of Everson’s curators, Garth Johnson, said although Weems’ influence was crucial to this exhibit, she was not involved as a co-curator. Instead, she served as a source of inspiration whose relationship with the museum opened doors to make this possible.

“Carrie Mae, I think, from the time she started to emerge as an artistic force in the 90s, has had a very long relationship with the museum; the museum put on her first major exhibition,” Johnson said. “She’s stayed an active community member here in Syracuse over all of those years.”

Weems’ legacy as a female artist of color extends throughout “Who What When Where” as other opportunities are extended to those from underrepresented backgrounds.

With the deaccessioning of “Red Composition” by Jackson Pollock last fall, the Everson made it their mission to use those funds to acquire works from women and artists of color. Several new acquisitions included work from Black artists whose works center on violence against members of their community. “Bang, Bang, You Dead!” by Ellen Blalock, “Waiting for Medgar: Jackson, MS” by Dawn Williams Boyd and “Major and Minor” by Jamal Cyrus all came from this fund and were included in the exhibition.

“Who What When Where” is timeless. It captures snapshots in these moments spanning generations. While most of these are American works, an international flair is captured as well. It explores the best and worst of humanity — why humans do the things they do, what it means to have a sense of self, and how we fit both individually and collectively into a broader framework that spans generations. It’s an incredibly powerful experience, and the ambitiousness of the exhibit challenges you to think about your own identity and the legacy you’ll leave.

However, the exhibition is overwhelming in a sense, which works both for and against the messages of grief, pride, harmony and violence present in the show. There is so much being thrown at you that you’re not sure where to look first.

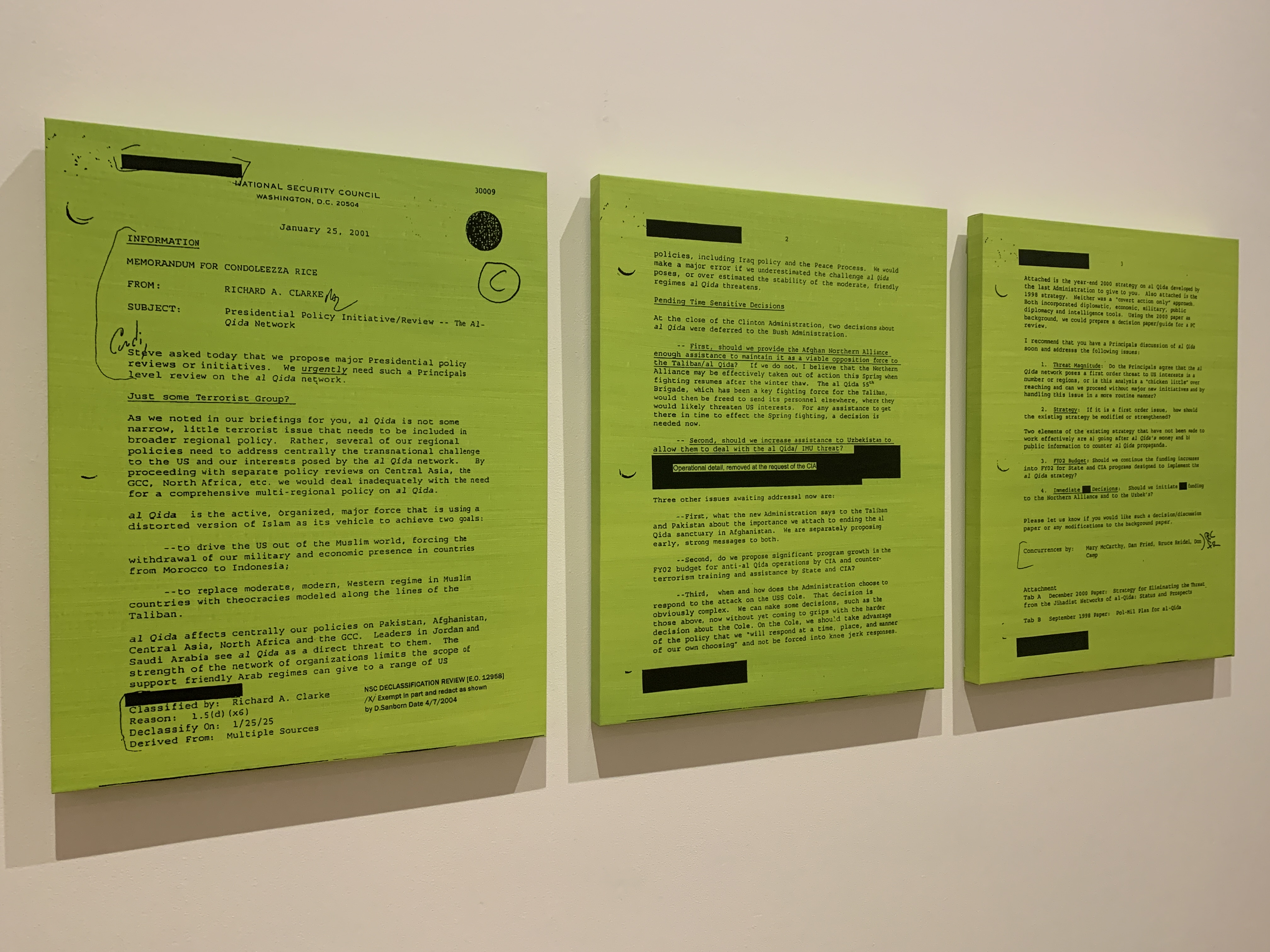

Some works are extremely chilling, especially Jenny Holzer’s “MEMORANDUM FOR CONDOLEEZA RICE GREEN,” a work that displays a memo written to Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice by Richard A. Clark of the National Security Council, warning of the dangers of the terrorist group al-Qaeda eight months before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. It is artworks like these that freeze you in a moment of time, showcasing the inevitability of violence that has plagued this country since its founding.

There are also moments of empowerment, specifically in Barbara Krueger’s “Untitled Suite (We Will No Longer Be Seen and Not Heard)”, containing pop-art-like print images with subtitles that provide a voice to those fighting against societal norms. This piece offers a sense of reconciliation among those of different backgrounds, which is the aim of “Who What When Where” according to the label copy.

In addition to works that were already present in the collection, the exhibit utilized its new acquisitions from its Pollock deaccession to contribute to the narratives present in the work based on Weems’ 1998 photo series, and it’s refreshing seeing the Everson’s mission to show more diverse artists by giving them a platform.

Although Johnson mentioned the museum’s history with socially conscious art — ranging from works confronting the social and political aspects of the Vietnam War, to putting on Yoko Ono’s first solo exhibition — this work isn’t finished. Moving forward, there is much to be done, and this exhibition is only a start. Changes must occur in the institutional framework — more curators of color, more staff from marginalized communities and more commitment to understanding and researching the works created by these artists.