Seamus Kirst: addiction and everything else

Seamus Kirst: addiction and everything else

Seamus Kirst passed out. He was 15, and his head went face first into the snow. He had been drinking with some friends outside in the middle of a Syracuse winter and blacked out. When he woke up, he was in a hospital bed, recovering from hypothermia. It wasn’t until seven years later that he acknowledged he was an alcoholic. During those in-between years, Kirst came out as gay, struggled with an eating disorder and graduated as the valedictorian of his class.

Last year, Kirst wrote a memoir that detailed his addiction, Shitfaced: Musings of a Former Drunk. Kirst’s book is one of dueling narratives. He was, by most standards, a stable, successful kid who also happened to be struggling with alcoholism. He didn’t hide his addiction, exactly, but he managed to function at a high level in spite of it.

“I tried to provide a more holistic picture of myself,” Kirst says of the book. “That way it’s more understandable. You can see how alcoholism can be a major part of my life, but still just one part.”

Now, Kirst is set to speak at Le Moyne College on April 3. His talk will cover many subjects that he also discusses in his memoir. The book is a meditation on his own identity and addiction.

Kirst said his initial goal in writing the book was to give those who struggle with addiction someone to identify with. He writes about the cliché of phrases like “it gets better” in his memoir, but deep down, Kirst believes in the idea of hope; as a 27-year-old in recovery, it may be hard not to. “It’s never too late to decide that you want to live, and live a stable, fulfilling life,” he said.

Scratching his eyes in a Starbucks in midtown Manhattan, Kirst realizes that he’s devolved into platitudes, but doesn’t seem to mind. “I can’t think of a better way to put it,” he says.

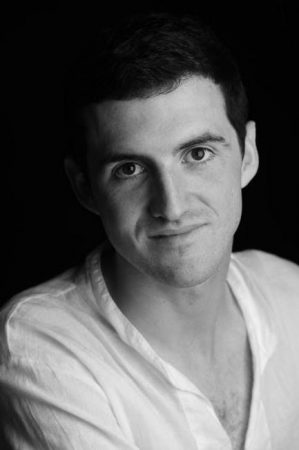

Kirst is dressed in a button-down shirt, cut-off shorts, and Birkenstocks. As he speaks, he plays with his face often. Kirst talks quickly but chooses his words carefully. He pauses occasionally, searching for the right phrase. His dark hair is trimmed tightly to his face, and his legs have to bend quite a bit to fit under the small table.

Shitfaced moves chronologically, but it never devolves into a traditional autobiography. Instead, it is constructed as a series of vignettes. Each is a moment Kirst remembers vividly, whether it involves alcohol or not.

Author Seamus Kirst will speak at Le Moyne College on Tuesday, April 3, at 7 p.m. in Grewen Auditorium discussing alcoholism and college.

Kirst writes about attending Brown University after graduating from Corcoran High School in 2009 and says his story of academic success is more of a rule than an exception. “I think there are tons of people like that,” Kirst says. “Plenty of people are just holding it together on the surface.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kirst is right. More than 10 percent of the alcohol consumed in the US is imbibed by underage drinkers, and over 600,000 children between the ages of 12 and 17 have alcohol use disorder, or are alcoholics.

Even as he struggled, Kirst found academic success in high school that would make him the envy of most students. Although Corcoran has only a 64 percent graduation rate, Kirst excelled enough to gain entry to an Ivy League university. Kirst sees his success in the classroom as an achievement, but also knows it was probably a part of his mental illness. “It came from a dark place,” Kirst says. “It was a pathological need to be a perfectionist in an unhealthy way.”

Kirst says when realized just how unhealthy he was, he decided to seek treatment—something he had resisted for years. He recalls believing that he was somehow better than those who sought it out. His decision didn’t come during any sort of climactic moment. Instead, he realized that he would die if he didn’t stop drinking.

According to Don Thomas of Square One Treatment, a nationwide rehabilitation network, Kirst’s illness and his reluctance to seek treatment aren’t uncommon.

“One of the difficulties in diagnosing alcoholism or addiction as a disease is it just plain doesn’t seem like one,” Thomas said. “It doesn’t look, sound, smell and it certainly doesn’t act like a disease. To make matters worse, generally, it denies it exists and resists treatment.”

Born in Syracuse in 1990, Kirst describes his childhood as typical, even if he held a certain disdain for the town he called home. When he was growing up there, Kirst saw his hometown as a remnant of an industrial era. Now, he’s safely outside its grasp and has garnered a certain fondness for his hometown.

“Now that I can leave whenever I want, it’s better,” Kirst says. “The air always felt still there, and it felt small.”

Part of Kirst’s lack of love for his hometown could have stemmed from his own father’s passion for the city, he said. Sean Kirst, a noted newspaper columnist in Syracuse for 25 years and a central character in Seamus’s memoir, loves the city. He thinks that growing up there, Seamus was exposed to a lot of different kinds of people. “We made a choice to stay there,” Sean says.

The elder Kirst had his own struggles with alcoholism, which Seamus details in the foreword to Shitfaced. Although Sean was initially hesitant to chronicle his own addiction, he eventually realized it was the only thing he could put in the foreword.

“Seamus’s work inspired me,” Sean Kirst says. “If we was being this freakin’ honest in the book then I think the foreword’s got to set the tone for where he’s going.”

For his father, the memoir gets at the messy truth of having a child with alcoholism. “There is no magic elixir, there’s no wand,” Sean says. “This sounds awful, but it’s true. There’s only so much you can do.”

Seamus never intended to follow in his father’s footsteps. Although he’s currently pursuing a career as a journalist, he initially wanted to be a lawyer. “I realized I loved writing,” Kirst says. He knew he could speak about issues that were important to him, and didn’t want to pass up that opportunity. “I’m privileged to have a platform,” Kirst says.

Kirst’s ability to write honestly about himself is evident in the book, in which he is unafraid to chronicle his struggles while being quite funny at the same time. “I have a pretty dark sense of humor,” Kirst says, explaining that it works as a defense mechanism. “It makes it easier to engage. It’s a helpful way to not get weighed down by it.”

According to Kirst, his feelings of disconnect from the world around him only fed a mental illness that was already there. Living in a city like Syracuse, where citizens mostly ignored the gay community, he said, only fed Kirst’s feelings about himself. “The scary thing about depression is it is apathetic,” Kirst says. “Depression isn’t distressing; it’s empty.”

In this first section of his memoir, Kirst writes about owning and loving a doll-version of Belle, from Beauty and the Beast. Kirst explores the shame he felt for loving the doll, and the questions it made him ask about his own identity. As a kid, Kirst didn’t understand his shame, a shame that would go on to haunt him for years. Near the end of the section, Kirst writes that he remembers thinking: “Why should I have to hide it?”