Scrolling on your smartphone might be killing your sleep

Scrolling on your smartphone might be killing your sleep

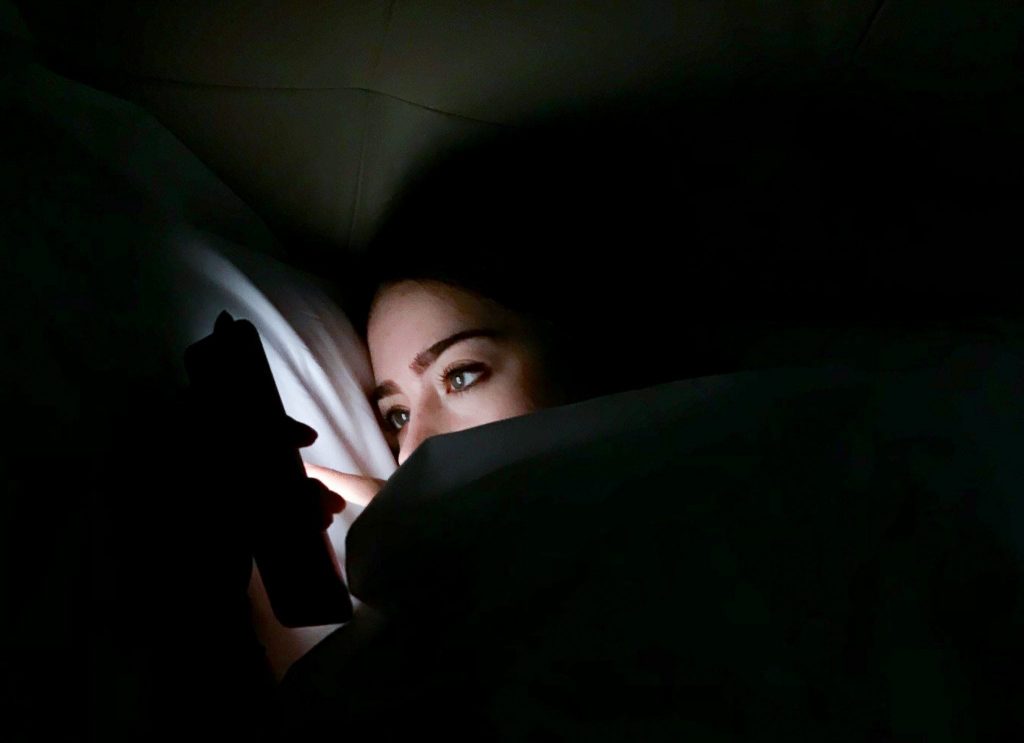

After a long day, Syracuse University sophomore Deniz Sahinturk climbs into bed, plugs her phone into her charger and begins her bedtime routine of scrolling through social media. She proceeds to “chuckles at memes” for an hour until she puts her phone down on her night side table at 12:30 a.m. But then she can’t sleep, so she checks Facebook one last time.

When she checks her phone next she’s not chuckling. It’s noon and Sahinturk slept through her morning class.

If this SU student impacted her sleep schedule by using her smartphone before bed, it wouldn’t be a surprise, according to a sleep study published in the Journal of Clinical Sleep in 2013.

The study conducted by Harvard University’s professor Charles Czeisler found that the more technological devices were used an hour before bed, the more likely people were to have difficulty falling asleep.

College students’ sleep may be taking the biggest hit; a survey of over 2,000 adults conducted by Harris Poll for the Webby Awards showed that 93 percent of millennials admit to using their phones in bed.

Smartphones and tablet screens emit “blue light” that decreases the sleep-regulating hormone melatonin in our brain, “throwing the body’s biological clock – the circadian rhythm – out of whack,” according to studies conducted by Harvard Medical School.

Though college students have an especially intimate relationship with their tech, kicking their smartphones out of bed looks like the solution to stolen sleep.

Sleep deprivation is a huge issue on the SU college campus according to Syracuse University’s Mental Health Promotion Specialist, Kristelle Aisaka. She often sees students masking sleep deprivation with energy drinks and coffee. “Anxiety and mood are worsened by lack of sleep because our brain loses the ability to process things in a healthy way,” Aisaka says.

Aisaka agrees that the blue light is disrupting everyone’s sleep, but acknowledges that part of the disruption is an effect of being constantly distracted and immersed in our screens.

Constant beeping or vibrating “keeps us on edge,” Aisaka says. “You think, ‘Oh, I need to respond to this,’ and that causes a higher level of anxiety that makes it harder for us to sleep too.”

Although most phones have “Do Not Disturb” and notification silencing functions, most students don’t use them. From working with students, Aisaka’s learned that many students have trouble avoiding their devices at night; it’s become a part of a “winding down” routine before sleep.

Before she goes to bed each night, Syracuse student Gabby Cajas likes to wind down with Instagram and Snapchat. Although she often plans for five minutes of screen-time, Cajas says it often turns into thirty minutes or more.

It’s when she catches herself dozing off in class that she realizes her screen time cuts into her sleep, her bedtime habit becoming a vicious cycle.

“I’m not even satisfied afterwards, because I always want to keep looking and looking,” the 19-year-old admitted. She added, “Sometimes I have to throw my phone off my bed.”

When college students can constantly communicate and interact through social media, the idea of disconnecting is a foreign one.

“It is the satisfying feeling of that you know, I looked at everything,” said Rachel Good, an SU student studying communications. “Sometimes news comes up and you might miss it. It is distracting, because that takes time away from sleep that I could be getting.”

Choosing to put the phone down and go to sleep requires self-discipline. Aisaka often sees that instead of confronting stress or emotions before going to sleep, college students turn to social media as a distraction. But when excessive technology use is causing someone to be sleep deprived, Aisaka believes training yourself to be mindful of technology consumption becomes an issue of maintaining self-care.

The Office of SU Mental Health Promotion advocates for mindfulness technique practice, because people who do mindfulness practices have shown to be better at dealing with emotional distress.

Cultivating mindfulness isn’t easy while living in a world of constant stimulation, but Aisaka encourages students to start by confronting unhealthy sleep habits and mindsets.

A first step is to use blue light filter apps that lower screen brightness and decrease the amount of blue light to warmer light, like the “Night Shift” mode on the iPhone or downloading the similar app “Flux”, recommended the SU Office of Health Promotion.

While these apps are a good first step, Aisaka said that not using devices at least 30 minutes before bed is ideal. A lead sleep medicine researcher at Harvard Medical School, Anne-Marie Chang, was also hesitant to fully endorse apps like Night Shift and Flux over complete screen-free time.

“Perhaps an hour or two hours (screen-free) before bed is really sufficient,” Chang told The Atlantic.“But perhaps it’s difficult for people to even do that.”

That’s why when notifications seem never-ending, Aisaka encourages students to ask themselves if small, immediate satisfactions like checking their Instagram feed one more time is truly worth losing precious sleep.