The Marshall employee spreads joy, positivity

The Marshall employee spreads positivity

If you sit in the lobby of The Marshall with Ken Culley for an hour, you could find yourself convinced that the world might be a good place.

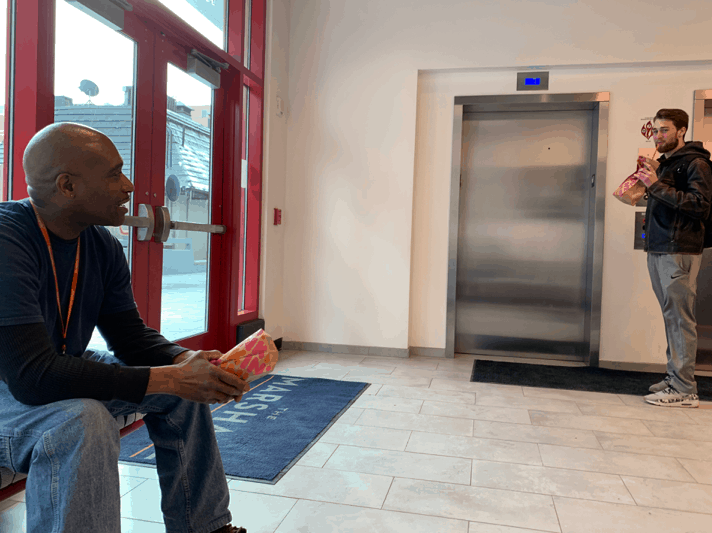

Culley was told to watch the front desk, so he stations himself by the door and opens it for those who come by. Some exchange of “Hi, Ken” and “Hello, dear” is heard with almost every person who passes. A tall, brown-haired resident walks in sipping a drink with two Dunkin’ Donut bags in hand. He walks near the elevator but looks at Culley, waiting for his acknowledgement and half-expecting his hello. Culley asks him how he is doing, although it’s clear he doesn’t know the resident’s name, because if he did, he’d use it.

“I’ve got an extra donut today,” the resident says. Culley is too polite to take it, except that the resident is adamant. When the elevator arrives the resident is off, but not before thanking Culley for being his radiant self.

Culley is the maintenance man at The Marshall, the new luxury student apartments just off Syracuse University’s main campus. He’s as new to the job as The Marshall is to the area but already a staple to its community. He wears a chunk of keys on a lanyard around his neck and faded utility pants that hold his pen, reading glasses and a box cutter. The bounce in his step mimics his upbeat character. The positivity he brings with him is infectious.

Alexis Martinez, who works at the front desk, says Culley’s persistent positivity makes her feel guilty for not always being able to return it. To this, he says what he always says: “that’s a beautiful thing.”

He tries to make the best of all situations. “He’s always trying to look out for everyone,” she says.

On move-in day, resident Kayla King met Culley in the elevator when he introduced himself to her. Whenever she sees him, he asks if she needs anything or simply about how her day is going. King might not know anything about him beyond his name but she feels comfortable enough saying, “I love Ken.”

As he cleans his way through The Marshall’s halls, Culley says hello to everyone, even if they don’t always reciprocate. Maybe they’re having a bad day or maybe they didn’t hear him, so he’ll try again next time because he believes in giving people the benefit of the doubt. Some residents make a mess leaving their garbage strewn across the floor of the trash rooms instead of in the bins, but Culley doesn’t mind much. He sweeps the plastic applicator of a used tampon into his dustpan off the floor. “That’s my job security,” he says chuckling.

Culley lives in Syracuse with his wife, two grown sons and two pitbulls. But unlike the rest of his family, he didn’t always live here.

When Culley joined the military in the 1980s, it was because he’d had enough of Chicago. He’d grown up on the south side of the city where gangs, drugs and death were parts of everyday life. Most of his friends were caught up in the violence, and the some 30 friends he grew up with eventually dwindled down to some five. He believes in God, which to him is a promise for better days and what saved him from the streets of Chicago. “Man, if it wasn’t for God, I wouldn’t be here,” he says. “I’d be dead, no doubt about it.”

Culley’s love for others is based on his parents’ demonstrations of it as well as their demonstrations against it. His mother was a pastor and his father was the superintendent of a construction job. The foundations of his upbringing kept him off the streets but still parallel to that life. His parents got divorced when he was 11-years-old. After a falling-out when he was 18, his mother kicked him out of the house, something Culley says he’ll never do to his sons.

He was stationed in Watertown in 2000 where he met his wife, only an hour from Syracuse. Their sons are old enough to care for themselves now, but Culley still feels protective of them. Every day, he tells his sons he loves them, something he heard from his father maybe ten times in his life. Culley finds it especially important for boys to hear it to help them stay off the streets. As long as his sons are happy, healthy and doing the right thing, there’s nothing more he could ask of them.

The strain on his relationship with his mother never fully healed, but Culley said he forgives her. He keeps an old speckled copy of her business card in his wallet. It reads: “Reverend Culley.” His father wasn’t religious like his mother was, but Culley says he learned his greatest lesson watching him manage his workers: “If you give a lot of love, you get it back.”

At 55 years old, Culley is content with his life but recognizes that it hasn’t been an easy one. “I ain’t got a lot to show for it but I’ve got my house, my family, my health – I’m cool with that,” he says. “And I got God!”

Culley establishes the atmosphere of The Marshall with his presence. Where Ken goes, positivity follows like a magnet. It almost makes you wonder if the halls of his old jobs are haunted by his absence.