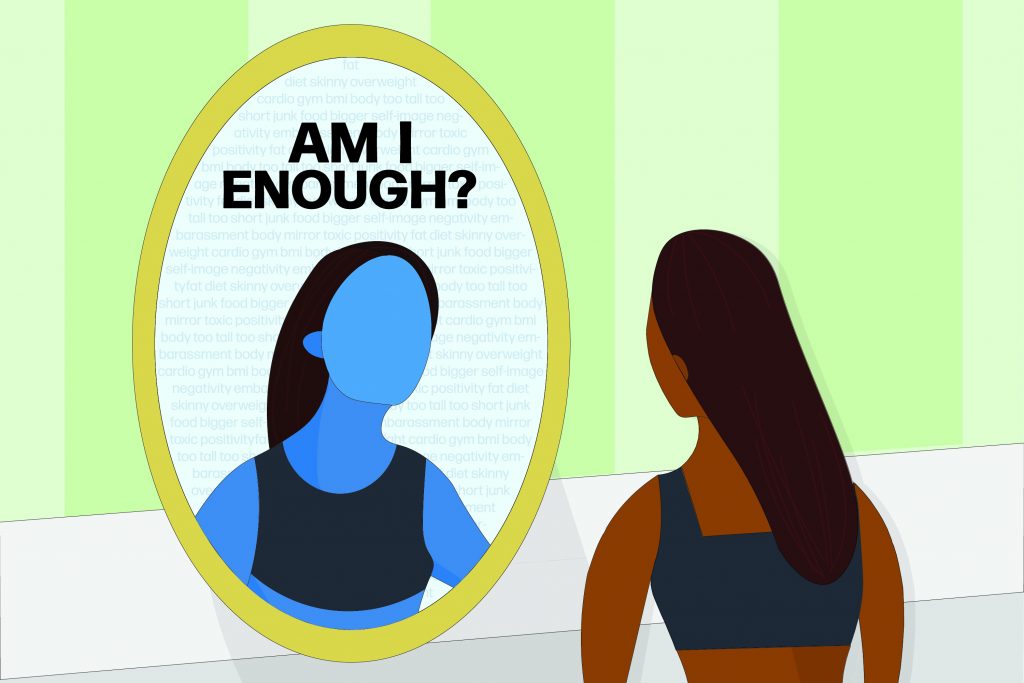

How the body positivity movement is failing young women

How the body positivity movement is failing young women

You’ll never find Britney Kirwan shopping at Victoria’s Secret.

When she was in middle school, the brand was inescapable. Images of models like Cara Delevingne and Gigi Hadid walking in the renowned fashion show wearing bejeweled lingerie crowded her Instagram feed. The models all looked the same –toned, tan and thin– and Kirwan couldn’t see herself in any of them, despite how much she wanted to. As a chubby kid, it did not go unnoticed by Kirwan that these models were idealized and praised for their appearances.

At 12 years old, she thought she’d cracked the code on how to look like them. She started by watching YouTube videos with titles like “Victoria’s Secret Model Workout”’ or “How To Get Victoria’s Secret Model Legs.” When that didn’t work, Kirwan resorted to under-eating and over-exercising, starving herself until her bones jutted out through her clothes.

Women are taught that there is something wrong with their bodies at a young age. In a study published in the National Library of Medicine, researchers found that girls under 19 were most likely to experience body dissatisfaction. Social comparison, talking about weight in a negative way and weight-related bullying were the most common reasons young girls reported being unhappy with their bodies.

While this is still a relevant issue, it isn’t why Kirwin resents the lingerie brand. In 2021, Victoria’s Secret announced that it would be rebranded into a company that includes women of all ages, shapes and sizes with female empowerment as the driving factor. Kirwan, now 21, sees it as superficial.

“It took them years, and I just think, ‘why are they doing it now?’” she said. “When body positivity is a trendy thing? It’s not authentic at all.”

The beauty standards for young women have changed since the height of Victoria’s Secret’s popularity in 2013. Body positivity -which gained mainstream popularity on Instagram in 2012- was created as a way to embrace bodies of all shapes, skin tones and sizes. As social media platforms like TikTok, Twitter and Instagram grew over the last five years, so did the movement. According to a study done by a researcher at the University of Nevada, by 2020 the #bodypositive hashtag was added to 13 million social media posts.

The roots of body positivity trace back to the 1960s. During this time, Weight Watchers also became popular in the U.S.. The idea of size acceptance gained traction in 1967 when author Lew Louderback published an article titled “More People Should Be Fat!” in The Saturday Evening Post. The piece detailed his wife’s experience as a woman whose body didn’t match the thin ideal of the time. Louderback argued that body discrimination is based on aesthetics rather than health and that, by refusing to diet, his wife noticed an improvement in her physical and mental health.

In theory, the movement is a breeding ground for love and confidence. But what began as a safe haven for women wanting to feel comfortable in their bodies has turned into a movement that prioritizes exclusivity and dictates who has the right to vocalize their issues with body image.

When Sarah Dickerson, a 19-year-old sophomore at Syracuse University, was three, her parents enrolled her in a ballet conservatory– the kind that shipped its students to Russia at age 14. She had always been tall, but in 4th grade she started to gain weight. Dickerson noticed that she was bigger than the other girls at the conservatory. It didn’t bother her until her instructor poked her thigh with her index finger and, in front of the entire class, told her to “get some fat off of those.”

“I felt ostracized because I was bigger than everyone. I didn’t fit the mold that they needed me to be,” she said. “I created a to-do list in my head of what I needed to do to be skinny.”

Online, she found guides on how to get skinny fast. Her hours of internet browsing also introduced her to bulimia and anorexia. The weight-related bullying didn’t stop as she got older, either. Dickerson noticed that it often came from girls her own age. One of the girls on her competitive dance team made a list of all of the girls that were skinny.

“I wasn’t on it, and at that point I lost a lot of weight because I had a growth spurt,” she said. “That was a really shocking moment for me.”

Similarly to Dickerson, Claire Schroeder, 20, grew up dancing. The environment was a breeding ground for negative self-image. Schroeder wasn’t born unsatisfied with her body, but the mirrored walls and frequent discussions about dieting in her studio brought Schroeder’s body image to the forefront of her mind. In middle school, she watched her mother cycle through various diets and weight loss fads, openly discussing how she didn’t like the way she looked.

“Puberty is when it got in my head because that’s when the body becomes a conversation point,” she said. “That’s when girls start really comparing how much they’re growing, and guys start noticing you.”

When she was in middle school, Schroeder fell down a rabbit hole of anonymous online communities that promoted disordered behaviors. Women would compare their bodies, sharing how much weight they lost and how little food they consumed to do so. In high school, Schroeder was hospitalized for an eating disorder. She looked healthy, which was an invitation for others to diminish her experience.

“When I would try to talk about my disordered eating, people would say, ‘She’s not skinny enough to have an eating disorder,’” she said. “I was actually dying. I had kidney failure.”

Today, Schroeder sees content on TikTok that promotes disordered eating and body image, except it isn’t anonymous. Schroeder is confident that if she shared her experience online, she wouldn’t be validated for the same reasons her struggles were brushed to the side in high school.

“The Body Positivity Movement has turned totally visual and external,” she said. “There are so many factors other than just what a person looks like that contribute to the big umbrella that is a healthy body image.”

Weight stigma isn’t unique to one type of person– it can affect those who are thin and those who aren’t. This stigma manifests in different ways for people across the weight spectrum.

Mckinley Leinweber, a junior at Luther College in Iowa, didn’t feel feminine until she went on birth control in high school. Even then, after she went up two cup sizes, her build was still narrow, almost androgynous. The feeling that she could not be attractive in a feminine way nagged at her. It manifested into a mental game of tug of war. On social media, she saw her body type being praised. In the school hallway, boys made snide remarks about her small chest size. Now 21 years old, this back and forth has continued in college. Part of her wants to gain weight but another part restricts what she eats to maintain her figure, Leinweber says. She can’t talk to her friends about how she feels without backlash.

“If I tell you I love my body, I’m conceited. If I tell you I’m unhappy with my body, I’m ungrateful,” she said.

Scrolling through TikTok, Leinweber sees videos of women larger than she is discussing their body struggles. If she scrolls more, she’ll usually come across a video of someone saying that women who look like she does have no place sharing their struggles online.

“They’ll say, ‘If you’re under this weight, or you’re under this height, or you look like this, then I don’t care what you think or how you feel,’” she said, “And they point to someone who has the same body as me and they’re like, ‘You made me want to starve myself.’”

There is a difference between the internalized body dissatisfaction Leinweber struggles with and the internalized self-hatred coupled with discrimination that heavier people and racial minorities face. The movement, which speaks about diversity, is dominated by women who fit society’s beauty standards. The University of Nevada study revealed that beauty standards like blonde hair and whiteness were common on body positive hashtags. Seventy percent of the most popular posts under #bodypositive and #bodypositivity were of white women.

Eating disorder therapist Jennifer Rollin believes that one of the movement’s biggest downfalls is the lack of diverse representation.

“Nobody is going to be fully free from all the body image pressures in our society until the most marginalized are free,” she said. “It’s important to highlight people living in really diverse bodies.”

This is especially true for social media. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care shows that increased social media use is correlated with negative moods and body image dissatisfaction in women. But Rollin says that online content can, in fact, improve body image. Following diverse content creators is the first step to diversifying social media feeds and For You Pages.

Rollin also notes that the movement promotes judgment, regardless of size. It’s easy to criticize and resent people on social media, especially when body positive content is so popular.

“Looking at the origins of your body image issues, ideally in therapy, and looking at what plays into it is so important,” Rollin said. “Finding those healthier ways to cope versus channeling all of your distress onto your body is also important.”

The movement has emphasized external features, and though it’s in a different way than Victoria’s Secret, women’s bodies continue to be dissected and scrutinized. Kirwan questions why physical appearance needs to be at the forefront of young women’s identities. She sees the “body positive” TikToks claiming only certain women have a place to discuss their relationships with their bodies. She sees brands like Victoria’s Secret rebranding to be more diverse only when body positivity is at peak popularity. As she began to view the movement in an inauthentic light, something clicked.

“I’ve now found more worth in myself that doesn’t have to do with how I look,” she said. “I’m studying journalism and that’s what I love to do. For me, it’s more important to write an article that I’m proud of than to look good.”

To Schroeder, the body positivity movement is like stumbling around a dark room with a lantern trying to find a wall. She is told that her feelings about her body are valid and she is told she is too skinny to struggle. She is told that the solution to her body dysmorphia and eating disorder is simple: just love yourself. She wonders how she can “just love herself” when the movement tells her she already should because she looks healthy.

“That’s the most toxic downfall of the movement,” she said. “That you just fake love yourself until you love yourself. And I don’t think that anything forced into fruition is ever sustainable.”