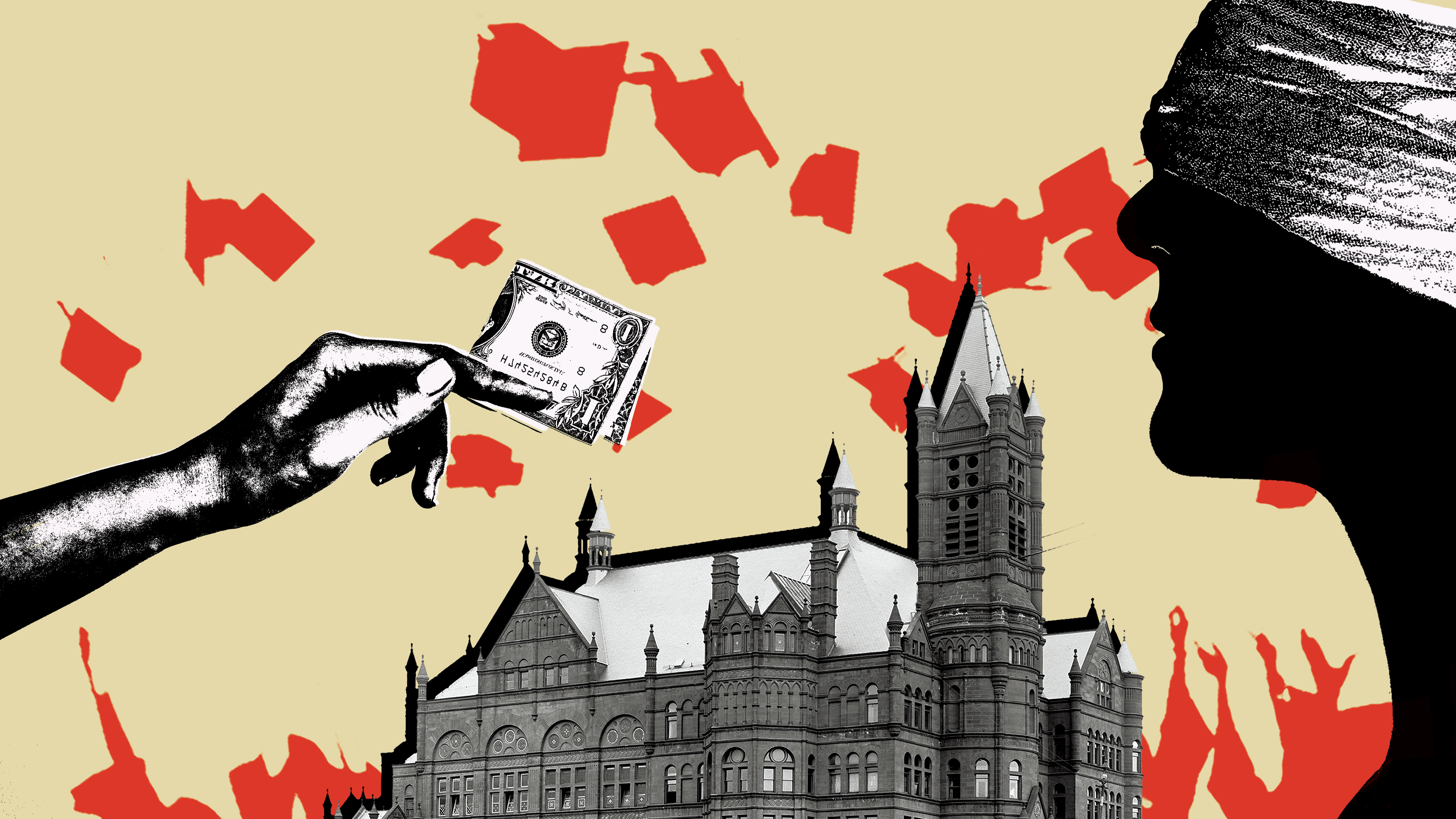

Crumbling Bridges

Crumbling Bridges

Tensions sow town-and-gown divisions between Syracuse University and the city it calls home.

an-Juba Arway would never recommend Syracuse University to anyone, especially someone who is a refugee or an immigrant.

“It’s just not a friendly school,” the 2019 SU graduate said.

During her time pursuing a master’s degree in public relations, Arway said she experienced a racist atmosphere and witnessed the tension between the campus and city. To her, it was not the welcoming Orange family and positive relationship with Syracuse that the university claims to foster.

Known as “town and gown,” the ties between a university and the city where it is located presents themselves in a myriad of ways from how campus and community members interact to the financial commitments and arrangements the two forge.

SU’s relationship with the city of Syracuse has been problematic at times in recent years from underfunding and insufficient outreach programs to misperceptions that deter students from wanting to engage with local residents. Princeton Review ranked SU’s town-and-gown arrangement among the most strained in the country this year, and SU was the only school of its size in the Top 10.

Arway, who now lives in Syracuse and works as the communications and community engagements manager at Refugee & Immigrant Self-Empowerment (RISE), said she can see the town-and-gown divide more clearly than ever.

“SU is not in touch with the communities, and most of the people who work at SU don’t even live in the city,” Arway said. “It’s almost like they’re on vacation in our town.

“They’re here to serve their time and then leave.”

Outreach: lasting or limited?

In an attempt to grow links with the city, SU created a citizenship and civic engagement (CCE) major in 2013 as part of the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs. Among the requirements in the major’s curriculum is tasking students with creating an action plan to aid a local organization.

Students come up with various plans, such as events, workshops, or policies aligned with a local organization’s goals. CCE program coordinator Amy Schmidt said the goal is to ensure the project “is responsive to the community.”

Formulating and implementing a cohesive action plan is difficult in just one semester, Schmidt said, so sometimes students will create a plan and pass the torch to the major’s next cohort of 30 students to see through. Other times, the students will create a plan that the organization can implement at a later date if resources or schedules don’t align at the time.

But when students graduate and leave Syracuse for good, they take their ideas, money, and resources with them, which Bennie Guzman has seen frequently as the communications manager at La Casita, a cultural center funded by the university.

“A lot of these students have great ideas … but they’re here for such a short and limited amount of time, and typically, they can only work on a project for one semester,” Guzman said. “So, you take this really great idea that can be implemented and done in a semester, you kind of rush it out — because you need it for a grade — but then what happens next year? What happens when you graduate?”

While Guzman acknowledged the major is well-intentioned, she questioned the follow-through on the university’s part. Oftentimes, she said, La Casita is forced to pause the action plans implemented because they are underfunded and understaffed.

La Casita’s executive director is the center’s lone full-time employee while the rest of the staff members are part-time or volunteers. Typically, the center hires students and receives funding from the university, but with the pandemic, volunteerism has noticeably declined along with money to support programming.

Guzman said support for community initiatives pales in comparison to that given to high-profile Orange sports such as basketball and football. SU recently replaced the Carrier Dome’s roof and added new features as part of a $118 million renovation effort.

“To SU, a non-profit that primarily works with working-class kids has a lot more money that goes out than it’s going to come in,” she said. “But if you put money into a football stadium, you get all the profits from those tickets, all the profits from that merchandising also profits from everything that you put into it, you’re going to get your money back from it.”

In the nonprofit sector, Guzman said the money is only going one way: out.

Guzman said SU maintains a strict business point of view because it’s where they’ll make the money back, which she chalks up to the school’s “lack of caring.”

Gina Iliev, director of family and community initiatives at the Early Childhood Alliance of Onondaga County and an alumna of SU, said the fault of the town-and-gown disconnect falls on the institution, not the students.

“Syracuse owes the city more than it gets, and it shouldn’t just come in students extracting or students doing projects and leaving,” Iliev said. “There needs to be a pipeline for students to actually want to stay and live and work in Syracuse.”

The danger stereotype

Convincing students to immerse themselves in Syracuse and venture off the Hill proves to be difficult, in part due to misconceptions that Syracuse is dangerous.

In Syracuse, the dividing line between town and gown is quite literal, with the university on the east side of I-81 and the city, with one the nation’s highest concentrations of poverty, on the west. The I-81 division is a long-standing reminder of redlining and urbanization that occurred in the mid-20th Century, separating predominantly white neighborhoods from communities of color.

Syracuse’s current population of 142,000 is 50% white, with Black residents accounting for 30% and Latino another 9.5%, according to Census estimates for 2019.

Iliev said SU’s lack of investment in local minority communities is a “textbook definition of a racist attitude, even if they would never admit it,” adding to the stereotype that anywhere outside university property is dangerous.

“To me, that’s flat-out racist,” she said. “It says that we have to protect our students from those other than them.”

The circulation of that narrative begins the moment students step foot on campus. Schmidt commonly sees students enter the program thinking the city is unsafe, only to realize that it is actually flourishing with communities of “people who are resilient and smart and strong.”

As someone who grew up in Syracuse, Schmidt said she always saw SU as keeping to its bubble and not necessarily making an effort to build strong bonds with the surrounding community.

“Here’s this huge organization that has millions and millions and billions of dollars, and you’re here — you’re educating students here — for four years, and then they leave,” she said. “(Students) are using our resources, and they’re not really giving back, and they’re not really interacting in a meaningful way.”

One of the biggest priorities is engaging students, Guzman said, and while the CCE program attempts to meet that goal, physical distance between SU’s campus and the city creates yet another obstacle.

From campus, La Casita is a 10-minute drive, or a 30-minute walk if a student does not have access to a car. There’s the Connective Corridor bus — which former Chancellor Nancy Cantor implemented as a way to drive students into the community — but it only stops at La Casita six times each weekday. For other bus route locations, buses circulate back-to-back all day.

“The resources that allow people to come to our side of town or our side of campus are very limited,” Guzman said. “Unless you have a car, you’re not going to be able to get to La Casita.”

In addition to the lack of transportation, La Casita is also located on Otisco Street in Syracuse’s Westside, which Guzman said bears the brunt of the dangerous stereotypes about “shootings, gun violence, gangs, and drugs.” She said she can tell when it’s a student’s first time venturing that far off campus because she can sense at least some hesitation.

“It does hurt our overall mission because students are too afraid to come to this side of town, because of something that may or may not even happen,” Guzman said, adding that “nothing has ever happened” in her two years of working at the center.

The proof is in the money

The “brain drain” — the phenomena of students coming to school in a smaller city and then leaving immediately post-graduation — can contribute to the town-and-gown separation, said Arway. If students weren’t “scared off” by the city, she said they might actually stay and get jobs in Syracuse.

When students come to the city and only for a four-year stint, she said it is hindering a potential investment in building a better future for Syracuse.

“As soon as they’re done, they take (their skills) to another city,” Arway said. “They’re helping another town’s economy. They’re not helping ours.”

In addition to the economic setback caused when students leave the city, the university is also classified as a non-profit in the city of Syracuse, meaning it is not required to pay property taxes.

Property taxes in New York are used to fund expenses such as public services and school districts. More taxed properties or higher property taxes means more ways to fund infrastructure, services, and schools.

In the city of Syracuse’s 2020-21 budget, 56% of all properties are exempt from taxation. These properties include churches, hospitals, and SU, which has more than 100 properties throughout the city, spanning beyond the main campus.

“Nobody’s paying property taxes, or very few properties are putting money into the city school district,” Iliev said. “That’s a real problem.”

No need to pay

Tax exemptions account for a significant portion of the total assessed value of the city’s tax-exempt properties, including Syracuse University, in the city of Syracuse’s 2021 annual budget.

SU does contribute Payments in Lieu of Taxation (PILOT), which non-profits typically pay, but there is no set minimum mandated to be paid. While the university is one of the largest employers in the area, it only agreed to voluntarily pay money to the city of Syracuse a decade ago.

That amount they do pay, Iliev said, is “nowhere near” the amount they would pay if they were required to pay property taxes.

In 2011, Syracuse.com estimated that the university’s real estate holdings totaled $630 million, and if it were taxable, the university would owe $24 million a year. That year, the university agreed to give $500,000 per year to the city, a contract that was renewed and increased to $800,000 in 2016. It is up for renewal again in 2021.

“It’s ridiculous when you consider how much (SU) students are paying,” Iliev said. “So now we have a city that’s incredibly depleted, that’s segregated in hyper-poverty … and then you have the university where that is not the case.”

The divide’s legacy

Despite setbacks and potentially harmful narratives that contribute to the separation of the Hill and the city, the non-profit sector is working to reconstruct a relationship built by former SU Chancellor Cantor that current Chancellor Kent Syverud has not emphasized.

“Nancy Cantor obviously was dedicated to fostering greater connections between the university and the community, and when Chancellor Syverud came in, it seemed like there was a turning away from that,” Schmidt said. “It felt like, ‘Oh no, is the university going to close itself off? Or are they going to go back in the bubble?’”

Guzman echoed similar sentiments, adding that when SU’s administration changed in 2014, the mission of the university also shifted, and with it, programs couldn’t survive. Community-focused projects disappeared, she said, and Syverud committed to a more introverted approach to the student experience, instead of to the Syracuse community.

SU Community Engagement and Government Relations vice president Cydney Johnson said the university “is always interested in being a good partner and a good neighbor” to the local communities.

During the pandemic, Johnson said, the university partnered with the local school districts to conduct online instruction training. In addition, she said that the university’s Artist in Residence, Carrie Mae Weems, created a campaign to teach COVID-19 safety tips to neighborhoods of color through artistic avenues.

Deconstructing The Divide

But despite those endeavors on behalf of the university, Schmidt said the gap is still prevalent and is exemplified through the actions of the students.

Some students, she said, don’t treat the city as a home. They just treat it as a temporary place and don’t worry about who lives in the city and relies on certain services.

“There’s always this level of lack of trust, I think, between the folks who live in the community and the students,” she said. “Students assume that the community will reject them if they go out there, and people who live in the community assume that students don’t care about them.”

The cyclical relationship reinforces itself. In order to make a difference, students have to be willing to go out of their comfort zones, and the university needs to start communicating with the people in the city, Arway said.

“I believe they could do more. They could get engaged more with the communities and they could also hold those professors accountable,” she said of SU. “Get involved. Talk to us first, get our opinion, hear from us.”