It’s Not Our Hill

It’s Not Our Hill

Indigenous activists and students say the university and state can do more to recognize the Onondaga Nation’s claim to the land SU was built on.

At the beginning of many Syracuse University events, the master of ceremonies starts by acknowledging the Native Americans who lived in Central New York for centuries before SU was founded 151 years ago.

“Syracuse University,” the acknowledgement reads, “would like to acknowledge with respect the Onondaga Nation, firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee, the Indigenous peoples on whose ancestral lands Syracuse University now stands.”

Who had the land in the decades before SU’s founding is a mystery, but how the Onondagas lost it is simple, says Joe Heath, Onondaga Nation general counsel: It was stolen.

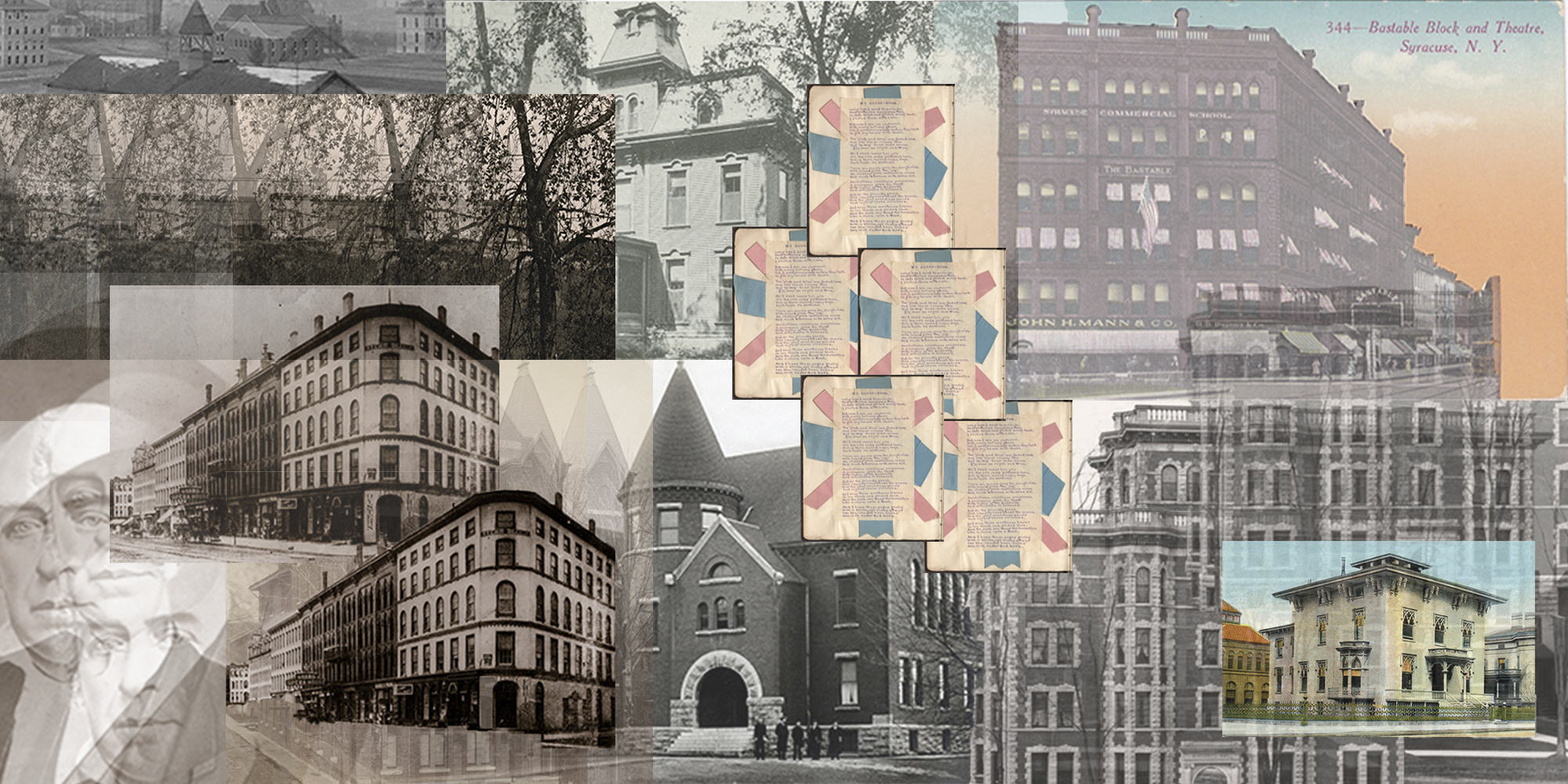

The SU campus offers many grand vistas, from the Hall of Languages, looking north at Downtown Syracuse and Onondaga Lake, or looking down on campus itself from Thornden Park, the white Dome roof serving as the backdrop for the red brick of the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and Crouse College. And no matter how far you gaze or what direction you look, when you are on the SU campus, you are looking at Onondaga Nation land.

Today, the school itself sits on 721 acres of Onondaga Nation territory. When SU was founded, 50 acres were purchased from George F. Comstock. Experts don’t know how Comstock ended up with the land the state took from the Onondagas.

Scott Manning Stevens, director of SU’s Native American and Indigenous Studies Program, said the answer likely lies in the founding of the city of Syracuse.

“It should be known,” said Stevens, who is a citizen of the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation. “It shouldn’t be so mysterious when it’s something as important as taking someone else’s land.”

The incursion of European settlers into New York began in the early 1600s, and through a series of military campaigns, forced relocations, treaties, and broken promises, white settlers began to displace the Onondaga and the other tribes of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

The land Syracuse sits on was purchased by New York from the Onondaga Nation in the late 1700s and 1800s in violation of the Trade Intercourse Act of 1790, Heath said. The act makes it clear that only the federal government can take Native American lands.

“The problem with the law is it gives no remedy,” Heath said. “There’s no consequence to anyone who violates the law.”

SU wasn’t involved in that illegal purchase, but that doesn’t lessen the university’s responsibility in acknowledging that the land was stolen, Heath said.

“Whatever title the university has traces directly back to the state’s illegal taking,” Heath said. “If I start with an illegal title to begin with, it doesn’t get any better no matter how many times I sell.”

The Onondaga Nation has asked the government to recognize the land theft, and in 2005, the nation sued the state in an effort to force that recognition. But in 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the case claiming it was “too disruptive” to declare the land was Onondaga, according to the Onondaga Nation website.

Yet the Onondaga Nation was not seeking to oust anyone from what is their ancestral territory, said Professor Philip Arnold, chair of SU’s Department of Religion and the founding director of Skä·noñh — Great Law of Peace Center.

“They specifically said that they’re not interested in removing anyone from land in their traditional territory,” Arnold said. “But they want to have a voice on how land is regarded, how it’s treated, what economic development looks like.”

The Onondaga Nation was hoping the declaration of their land through the courts would help them find fairer remedies.

“What we had hoped was that we could get the declaratory judgment that says, ‘The land’s taken illegally’ and then use that as leverage to find some kind of fair resolution of this historic harm,” Heath said. “Unfortunately, we were denied that because, once again, the courts made up new rules, and rule number one for Indian law is Indians lose.”

SU is home to 350 Native American students and has more Haudenosaunee students than any other college, Arnold said.

Arnold said the university can do more to right this historic wrong by expanding opportunities for Native students to attend SU.

“After a kind of symbolic land acknowledgement, which is good, then how do we deal with that?” said Arnold, whose wife and children are Haudenosaunee. “Well, part of that is you give scholarships to Haudenosaunee students.”

In December 2019, during the #NotAgainSU movement, a group of Indigenous SU students wrote a letter to the university proposing changes to make campus more inclusive for Native Americans. The Indigenous Student Concerns and Solutions proposal included preserving the Native Student Program’s residency at 113 Euclid Ave., hiring Indigenous mental health counselors, creating a Native and Indigenous Studies major, and extending the Haudenosaunee Promise and Honor scholarships to graduate students, among others.

Doctoral student Ionah Scully is part of the group of Indigenous students working with SU officials to make campus more inclusive. SU has been receptive to the concerns Indigenous students presented but have not been as quick to act as activists would like, said Scully, who is Cree Métis of the Michel First Nation.

“It’s like pulling teeth to get responses, to get answers,” Scully said. “We take one step forward, three steps back.”

The burden of pushing the university forward on these issues falls on the students, who often have to follow up multiple times to get responses or updates. When the university does agree to sit down with students for discussions, officials seem unprepared for conversations or to provide answers, Scully said.

“Then they get to the meeting and they forget why we’re there,” Scully said. “It feels like we start over.”

Danielle Smith, an SU alumna involved in the effort, said even coordinating meeting times with SU officials is difficult.

“We asked multiple times for admin to send out a Doodle poll of some sort to figure out the best time to meet for all students and admin involved,” Smith, who is from the Onondaga Nation, said in an email. “And we usually just get one or two times that work for them and we have to adjust our schedules. It may seem like an oversight on their part, but to us, it is this kind of inconsiderate behaviors that make us feel invisible.”

The students have been coordinating an Indigenous art installation for campus for a year. SU officials promised a mock-up of the installation and a preliminary contract for the artist, who already created the art piece, before the next meeting between Indigenous students and administration.

The student group has been waiting for these deliverables since November and followed up three times, until SU informed them they couldn’t provide the mock-up and contracts until they met again.

The students want transparency.

“We agreed to this,” Scully said. “Why did you say you could do it if you can’t do it? Because then we might have had different questions.”

The university will often say they are working on the promised initiatives, like the art installation, but no progress is made, Scully said.

“We’re basically in no better position than we were a year ago, year and a half ago, more than a year and a half ago when we started the whole process,” Scully said.

SU Chancellor Kent Syverud denied multiple requests for an interview.

Despite the obstacles Indigenous students face, they have been effective in holding the university’s feet to the fire, Stevens said.

Logan Booth, a senior at SU who is Seneca and from the Onondaga Nation, said these changes could help make the first-year Indigenous experience at SU more welcoming.

“I think a lot of us just had some pretty negative experiences going in,” Booth said. “I felt pretty disconnected from the university as a whole and I kind of had to find my people.”

For Booth and many others, the Native Students Program represents a community and support network that Indigenous students struggle to find elsewhere on campus. Ethan Tyo, who is Akwesasne Mohawk and an SU graduate student, is one of the students who helped create the proposal submitted to the university. Tyo said this proposal would provide more resources and help build community for Indigenous students.

“A lot of especially Indigenous students struggle with that sense of belonging and kind of community aspect,” Tyo said. “The Native Student Program has helped kind of on the other side of things helping to give that sense of belonging while on campus.”

The Native Student Program at SU offers students more compared to other schools, in large part, Booth said, as a result of the efforts of Assistant Director Regina Jones.

“I feel really safe and I can come to her with whatever problem I may have,” Booth said.

SU offers a Native American and Indigenous Studies minor, which students want to see turned into a major. When asked why there isn’t already a major, Stevens said that goal requires a certain level of demand and investment in infrastructure, faculty and staff, accreditation, office space, and more.

“There’s a long way to go before just jumping into a major, and I wish it were easier and more clear cut,” Stevens said. “The university is not the enemy. They want the best for student experience, they want our alums, all of you, to be successful.”

With the proper investment, Stevens added, SU could become a leading center for Indigenous studies because it’s in the center of Haudenosaunee territory.

Indigenous students are also working with SU and the Onondaga Nation on drafting a new land acknowledgment for the university. The proposed expanded acknowledgement would explain “the necessity of the statement, providing historical, political, social context to those unfamiliar with Haudenosaunee culture and history,” according to their proposal.

Land acknowledgements are only worthwhile if they note the responsibility that comes with occupying that land, Stevens said.

Deconstructing the Divide

While some students appreciate the ceremonial acknowledgement of the stolen lands SU sits on, they also see it as performative if it doesn’t lead to tangible action that creates an inclusive and equitable environment for Indigenous students on campus.

“We’re pushing the envelope as much as we can knowing that there’s only so much land acknowledgements can do,” Scully said.

The draft asks people to consider their responsibility and relationship to the land, and the people who are Indigenous to the region. The statement also uses language in the present tense.

The new land acknowledgement must be approved by the Onondaga Nation Council and the university before being officially adopted.

“It was important for us to remind people,” Scully said, “that this is still ancestral, continuously inhabited, Onondaga Indigenous land.”

Indigenous students say they are tired of waiting for equity and are ready to change their tactics if the university doesn’t act soon.

“I’m no stranger to protest and to direct action,” said Scully, adding “we’re asking for breadcrumbs.”