Stanford professor discusses weed legalization at Maxwell lecture

Stanford professor discusses weed legalization at Maxwell

Marijuana. Cannabis. Ganja. Pot.

The popular drug may have a variety of names, but to Stanford Prof. Keith Humphreys it has just one:

“It is what we call it,” Humphreys said. “It’s just a weed.”

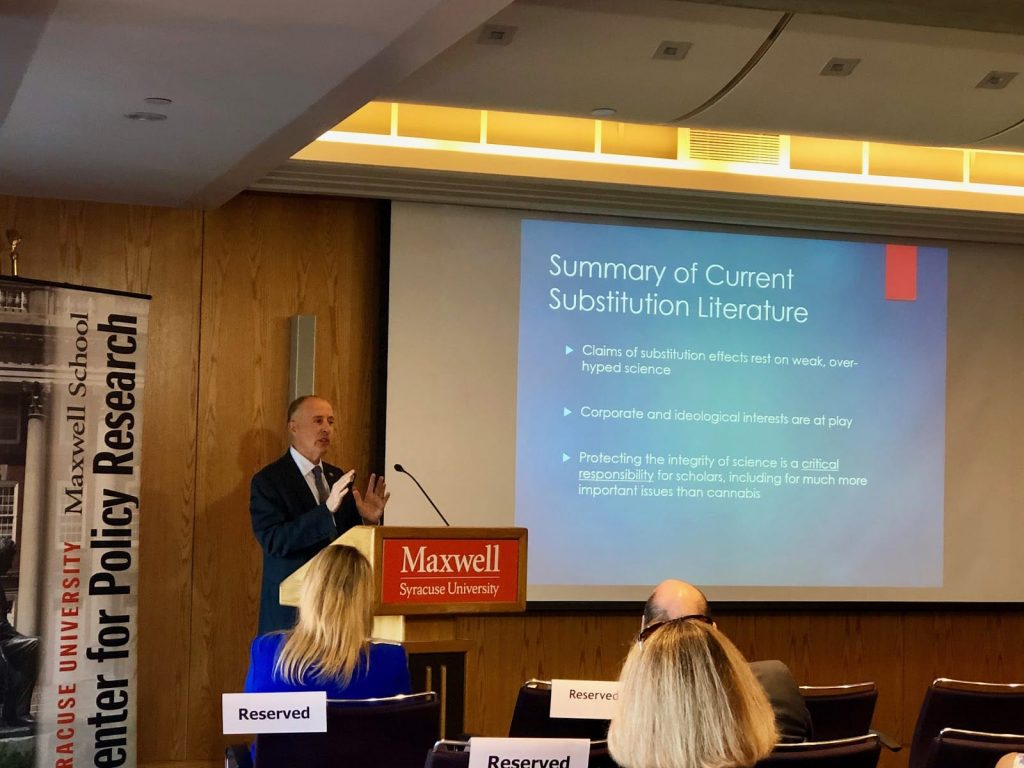

The Maxwell School welcomed Humphreys on Thursday for the 31st Herbert Lourie Memorial Lecture on Health Policy to share his expertise in addiction, public policy and health matters as it relates to the controversy surrounding the prospects of decriminalization and legalization.

Some in the audience of Syracuse students, faculty, staff and community members may have been looking for Humphrey’s advice as to how the United States is going to resolve the ongoing national debate, however, he didn’t have the ultimate answer

Humphreys explained that there are countless ways the U.S. could choose to approach the federal legalization of marijuana. He discussed the Dutch approach, selling marijuana only in “coffee shops,” or the Spanish’s tact, which is to have designated “clubs” where you can freely smoke.

“But of course the U.S. will have to do things its own way,” said Humphreys. “And in this case, I think it’s warranted.”

Citing U.S. exceptionalism, Humphreys said that the way this country’s size and diversity has created legitimate factors when it comes to handling the emerging marijuana market.

In the current political climate, there are two opposite ends of the spectrum being discussed when it comes to the legalization of marijuana, said Humphreys. Either society abandons the legalization conversation entirely — an unlikely feat, he said — or it becomes legalized nationally and commercialized similar to the tobacco industry.

Humphrey’s said there are many ways to manage the legalization, including how liquor is regulated in some states, such as Virginia or Maryland, where there are government-run stores.

The government would control the output of the substance, and thus be able to mitigate harmful effects like over-advertising or false information, but would still be able to reap the benefits of tax revenue. Humphreys said that this method would minimize corporate greed taking over the industry and becoming another “Big Tobacco.”

SU alumni and internal communications specialist Joyce LaLonde questioned Humphreys about the looming possibility that illicit pot dealers would come out of the shadows to sell legally.

Humphreys explained that the research simply isn’t available because marijuana hasn’t been legalized for long enough to accurately measure these efforts. But he noted in many cases, pot dealers have criminal records that would prohibit them from obtaining a license to sell legally.

As with the questions of dealers, Humphreys is adamant that significantly more research is needed about legalization’s impact to help inform the public and create policies.

Humphreys said the weed that “your parents smoked in the ’80s” is drastically different from the “new” cannabis circulating today.

“Pre-2000s marijuana had about 4 percent THC in it,” Humphreys said. “Weed nowadays has about 20 percent THC.”

Humphreys reiterated there is little data about the higher potency in today’s pot because few formal studies can be conducted on the banned substance. Once that kind of research happens, then policies can be set similar to how alcohol consumption is managed to efficient field tests for people driving under the influence of marijuana.