Neal Powless: SU Ombuds brings a message of healing to a polarized world

Neal Powless brings a message of healing to a polarized world

Head south from Syracuse University on I-81, travel about 15 minutes down to exit 16, and arrive in a sovereign nation, a sovereign nation from which, should you fly a drone or perhaps climb up on one of the region’s rolling hills, you can see the SU Carrier Dome glistening in the near distance like a snow-covered peak.

This is Onondaga, where Neal Powless, of the Onondaga Eel Clan, grew up and has lived most of his life. The reservation looks now like any rural American town, but the matrilineally structured nation is worlds removed culturally from the surrounding patriarchal, dominantly white society.

In the heat of ongoing #NotAgainSU protests on campus, Powless recognizes the escalation of bias incidents here as a reflection of our national polarization and tradition of prioritizing some voices over others.

“I see how systems impact individuals. I understand how these big hierarchical systems grind people up—” He takes special care with those last three words, his voice dropping to a whisper.

“And understanding how that same system has ground up my ancestors too, there’s something that we can all share.”

Powless, who at 45 now works as the University Ombuds (a neutral and confidential campus resource for conflict management and facilitated conversation), thinks it’s the buildup of ego and an I’m-right-you’re-wrong social climate that gets us into trouble.

For him, it’s not a question of determining black-and-white facts but of uncovering individual truths — bringing every voice to the table and validating the experience of every person, even if they might seem to contradict one another.

“I think that the majority of the world wants to live in the gray area and wants to be heard,” Powless says. “And at the end of the day in order to be heard we have to listen.”

To Powless, creating spaces where every voice is valid has a lot to do with stories.

He has always seen the world through a narrative lens: As a kid, whenever he and his father would leave a movie, his dad was often astonished at how much his son could quote from the film. For Powless, who now has a growing IMDb page in film production, movies have always been a window into an alternative perspective, another person’s truth.

Powless is often recounting a story — maybe it’s the story of previous Haudenosaunee spiritual leader Leon Shenandoah, or maybe it’s the story of that time he met Jerry Seinfeld — but he is also always listening to stories. His pursuit of degrees in psychology and counseling were a product of that same theme: how do I better understand my narrative and help others to do the same?

Within the walls of the SU Ombuds office, his take on being an “ear to the people” entails both hearing each person’s story and helping them to take ownership of it themselves.

Powless’s native name, Hawenawdies, translates to “his voice is heard among the people and he brings a message.” He long struggled to figure out what it meant to live into that name. Who was he to know what was right or wrong, or to speak for anyone else’s experience?

“And then I realized I just had to share my own story, my own experience and how I understood it, internalized it, and say this is my experience,” Powless says. “You may experience another indigenous person in another way but this is mine.”

Regardless of what comes next in terms of diversity and inclusion at SU and across the U.S., the conversation about identity and inter-group injustices has been opened. In Powless’s mind, facilitating that conversation and listening to every voice is the best place to start.

At Onondaga, if you stand on the deck of his childhood home, you can make out through the trees the raw, Tyvek wrapped façade of the house Powless and his family are building. It’s been more than six years since he lived along the shores of Hemlock Creek, but now its tall, waterside phragmites will populate his new backyard and lead down to the stream directly from his house. The voice of the rushing water resonates in the open air.

As Powless admires and listens from the slate stone perch behind the plywood structure, it becomes clear that the appeal has nothing to do with the house itself.

Growing up, he found many meditative moments along the creek, often from the security of his own secret nook by the small bridge at the end of the road.

The stream and the thoughtfulness it brought him has been a source of healing throughout his life. His story is the same story of mindfulness and healing that flows through many generations and centuries of his people, the same narrative he believes will allow us to grow into a more peaceful and collaborative space as both a university and a global people.

Hawenawdies. His name is a sentence, a calling.

“To be a messenger, I have to be able to listen,” Powless says. “I have to hear that story.”

A story of survival, a story of healing

By 4 p.m. on April 21, 1779, the American Continental Army had burnt all of Onondaga to the ground. The colonel in charge of the expedition reported that 50 houses, vast stores of corn and beans, and all livestock were destroyed — part of a scorched earth campaign commanded by General George Washington.

The Clinton-Sullivan Campaign is not a popular (if mentioned) passage in U.S. history books. But for the Onondagas, it is a pivotal moment in their survival.

Powless listened to this story two years ago at Tsha’ Thoñswatha, the Onondaga Nation fire barn, with others training to become facilitators for the Witness to Injustice blanket exercise. The multi-hour activity, conducted at pop-up locations by the local organization Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation, allows participants to hear the history of North America’s colonization and experience it from the native perspective.

Yet, a destroyed Onondaga is not the end of the Clinton-Sullivan Campaign story. The threat of famine imminent, Powless’s ancestors were saved by cicadas — more specifically, this region’s cicadas that explode in numbers only once every 17 years.

Two years ago, the 17-year cicadas had again returned. They jostled and buzzed in the woods on the reservation surrounding the fire barn. Powless vividly remembers the sound, that frightening sound of survival, a persistent hum that serves as a reminder: “We’re still here.”

Powless had been told about the blanket exercise by his wife, Michelle Schenandoah of the Oneida Nation Wolf Clan, who herself had recently been blown away by a session of the exercise at the Matilda Joslyn Gage house in Fayetteville.

The couple are now trained facilitators for the exercise, but it is only the surface of the work they do both individually and as a team to bring deeper understanding of the land and its native people into the mainstream.

For example, Powless has traveled and spoken internationally for 25 years to raise awareness for indigenous values; Schenandoah founded Rematriation Magazine to empower indigenous women in reclaiming their identity and to bring to light the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women.

They also co-founded Indigenous Concepts Consulting, through which the duo assemble lectures, workshops, and advising intended to share their culture’s core teachings and how they can be applicable today throughout society.

Schenandoah and Powless navigate the modern re-framing of their teachings together, often through deep conversation shared over hours-long car rides to various events.

The story of their marriage is itself a story for the ages — at least in the eyes of Michelle’s mother, Oneida Faithkeeper Diane Schenandoah, who is currently working on a screenplay that will tell the tale.

The Onondagas and the Oneidas have had a historically rocky relationship. During the American Revolution and the very same Clinton-Sullivan Campaign, controversy erupted between the two nations as the Oneidas took arms with the American Army.

As the legend goes, an Oneida man and an Onondaga woman were married during that time of tension. The couple fled in a wooden canoe on Cazenovia Lake, but the boat capsized and remains under water to this day.

More than 200 years later, Powless and Schenandoah married on June 6, 2015 and held a healing ceremony that morning on the same lake’s shores.

As part of the ceremony, the couple gave a traditional offering of tobacco, which is associated with giving thanks and sending prayers to all creation.

The couple continue to strengthen that connection and often introduce themselves to waters whenever they travel.

“I feel like I have to do something,” Powless says, standing on the shore of Onondaga Lake. Removing his right glove, he kneels on the rocky beach. He cups the water in his hand and then releases it, repeating the motion as he looks across the water’s surface and offers two silent prayers of renewal.

This impromptu ceremony marks the first time he remembers being able to physically touch the water. It seemed fitting for the site where, as oral tradition tells, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy was born over 1,000 years earlier.

Understanding his roots

In his hand he had one pencil, and he snapped it. But then he took six pencils, and he couldn’t. As one you are weak, but together we are strong.

William Dempsey, a current high schooler at East Syracuse Minoa Central, recalls this story, a particularly memorable one from Coach Powless on the sidelines of a lacrosse match.

It is a favorite of Powless’s, the symbolism of the bound arrows from the Peacemaker who united the original five nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, “the people of the longhouse.” The Peacemaker is told to have planted the Great Tree of Peace at Onondaga, the “Central Fire” of the confederacy, under which the warring nations agreed to bury their weapons, greed, hatred, and jealousy.

The strength of the bound arrows is a symbol whose influence Powless sees in the 13 arrows gripped in the left talon of the eagle on the seal of the United States, just like the influence he sees on the founding fathers and in the U.S. government from millennium-old Haudenosaunee democracy. To Powless’s dismay, the Greeks usually get all the credit.

Lacrosse, too, has its own roots with the Haudenosaunee. Deyhontsigwa’ehs, also known as the Creator’s Game, is in part responsible for peacefully bringing together the five nations at the confederacy’s founding.

The Haudenosaunee continue to play the game today with the same connection between the sport and spiritual healing.

Powless is something of a celebrity in the modern lacrosse world. But he wouldn’t be the first to let you know.

“He’s a very humble person,” Dempsey says. “If you didn’t know anything about lacrosse or anything about Neal, you wouldn’t know about who he is.”

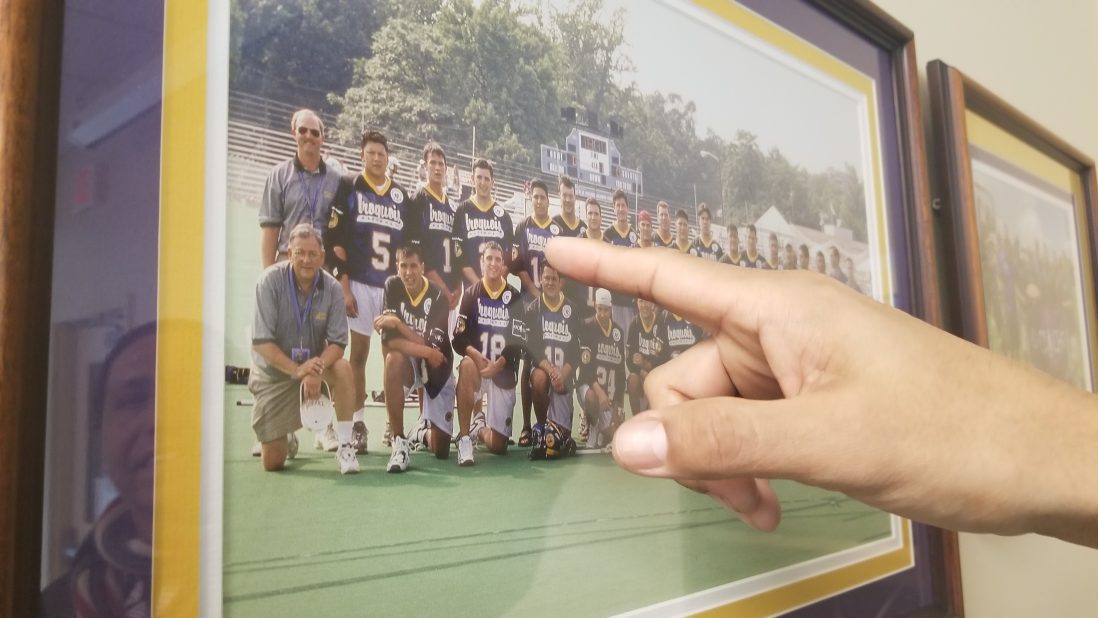

On the books, Powless is not only a three-time All-American lacrosse player from his time at Nazareth College (’98), but also the first Iroquois Nationals player to make the men’s All-World Team in 2002. He played for the Nationals at the World Lacrosse Championships four consecutive times in 1994, 1998, 2002, and 2006. He has also played for several professional indoor (box) lacrosse teams, including the National Lacrosse League (NLL) Rochester Knighthawks when, coached by Neal’s older brother Barry Powless, the team won their first championship in 1997.

When Dempsey played for the bantam-level Onondaga Redhawks three years ago and met his coach, his first thought was along the lines of “Woah, that’s Neal Powless.”

Powless himself has occasionally played for the Redhawks, whose 21-and-up team is a member of the Can-Am Senior B Lacrosse League, and as a part of which Powless earned two of his five championship rings in 2010 and 2014.

Running across the floor at the Onondaga Nation Arena, Powless received a pass from number 14, friend and teammate Tyler Hill. With a split-second fake at the goal, Powless threw off his opponent before passing the ball back to Hill. Within two more seconds, Hill had scored the goal.

The fierce eye of a Haudenosaunee lacrosse player looked over their chemistry on the floor from his place twenty feet up on the arena wall, the face of the official poster for the film Crooked Arrows (2012) which had been released in theaters just two months earlier. Powless, a co-producer on the film, is proud the giant world premier banner made it home to Onondaga.

A few years earlier, Powless had announced to the Redhawks locker room that a film crew was over in Lafayette, looking to cast indigenous athletes for a story about a native high school lacrosse team.

Hill, originally from Akwesasne (Mohawk) and now 32 years old, jumped at the opportunity and was soon cast as Silverfoot, a lead character in the $1.8 million grossing film.

Being on set with childhood friends, filming the first Hollywood movie about the sport and its connection to his people, the sport Hill has himself played with a spiritual connection since he was three or four years old, was surreal. And there was Neal, his teammate acting as a cultural advisor on the movie, doing his best to make its representation as authentic as possible.

Hill will admit the film does have some clichés, and Powless too will tell you about the give and take involved in being a cultural consultant for a large-scale motion picture (an ombuds-style work of expectation management in and of itself), but he is immensely proud of the production and the way his community banded together and gave the film their all.

“It’s always a positive outlook from Neal,” Hill says. “He’s always looking up, and he’s always trying to improve any situation that he can, and that’s on the field and off the field.”

Skä•noñh: a greeting of peace and wellness

Powless stands outside the 30-year-old building and its recent addition of a Haudenosaunee national symbol — with its iconic white pine tree, the Great Tree of Peace and its Great White Roots joining equally the Haudenosaunee’s five original nations — now emblazoned in the stones above the museum’s entrance.

“This was not how it was when I was a kid. It wasn’t somewhere we wanted to go,” Powless says. “But now, it feels good.”

In the mid-1600s, an expedition of French soldiers and missionaries built a fort on Onondaga Lake’s southeast shore, calling it Sainte Marie de Gannentaha. The fort was abandoned within two years as tensions with the local people escalated.

A modern-day replica of the mission, known by locals as “The French Fort,” has stood alongside Onondaga Lake Parkway for 87 years.

The site has been long known for its living history demonstrations of seventeenth century life at the fort, and its 1990s renovation into “Sainte Marie Among the Iroquois,” which included a new visitor’s center that traced the early travel routes of French explorers and their encounters with the region’s native people. After some years of budget failures, Sainte Marie officially closed its doors.

Recreated less than five years ago as the Skä•noñh – Great Law of Peace Center, the site is now a heritage center that tells the story of the Haudenosaunee from the indigenous perspective, through both physical displays and interview footage of Haudenosaunee people and allies.

On the Center’s second floor, Powless stops at a glass case displaying a Two Row Wampum belt. The belt represents the first treaty ever made between European and American Indian Nations in 1613, outlining a mutual commitment to friendship, peace between peoples, and living in parallel forever.

Powless’s father, Chief Irving Powless Jr., was a tireless advocate for modern-day recognition of the Two Row and the roughly 400 treaties, ratified by Congress, that the Haudenosaunee signed with the U.S. — many of which the U.S. has not upheld.

Neal’s mother-in-law Diane Schenandoah, as the daughter of a clan mother, sat in meetings her whole life with Chief Irving Powless.

“He was a very poignant person in knowing who we were as indigenous people and bringing our treaties to light,” she says.

Schenandoah’s daughter Michelle, who has degrees in law and taxation, studied under Chief Irving Powless before she and Neal got together.

“I love Neal. I just love him,” Diane Schenandoah says. “He’s an outgoing, friendly, intelligent, wonderful human being, and I really appreciate the fact that he was raised with his father’s guidance and that comes out in who he is.”

Powless has a story about growing up as the son of a chief:

Being the youngest of four siblings, Powless was born at the same time his father was transitioning into his role as chief and encouraging a return to indigenous tradition within the community. For Chief Irving Powless and his family, part of the example he wanted to set meant no more celebrating Christmas. Neal was the only person in his family to never celebrate the holiday.

He recalls many an astonished cashier during the holiday season when he would accompany his mom to the register to purchase a toy in November or, better yet, December. Their reaction always seemed to ask his mom, “Are you really going to let him see you buy his present?”

Powless was always quick with a response: “Yeah, and I’m gonna play with it when I get home, too!”

For young Powless, these interactions were a chance to show that he was different, that his family lived outside the Western cultural mainstream.

“And I used to love that feeling,” he says. “I used to ask for toys in that time just to kind of have that question, that conversation with people.”

As an adult, Powless continues to seek out conversations that share varying perspectives and challenge the expectations of both sides of the interaction.

The last time Powless visited the Skä•noñh Center was in October, when the Center held a commemoration event for Chief Irving Powless, just under two years after his death.

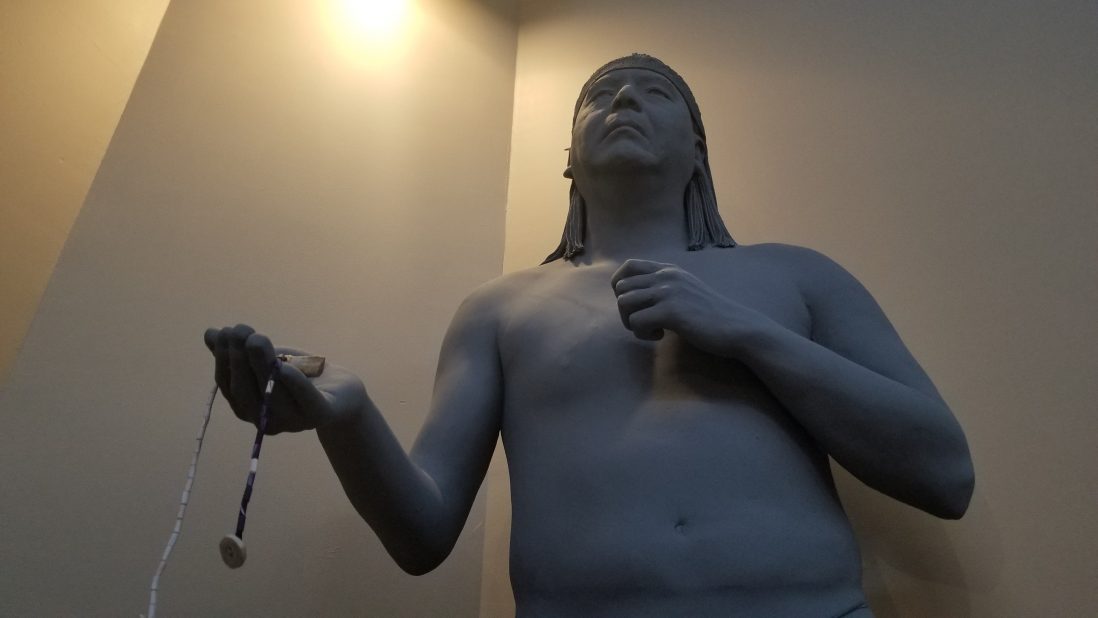

Walking in from the parking lot, Powless remarked that his father had allowed a sculptor to cast his own face and his son Barry’s for statues that would become part of the Sainte Marie Among the Iroquois exhibit. The statue with Chief Irving Powless’s face is still at Skä•noñh, moved to a prominent outlook beside the landing of the staircase leading to the second floor.

Now, Powless stops on the steps, looking up at his father’s preserved image.

“People say that I look a lot like him,” Powless says.

He pauses, taking a moment to meditate on his father’s memory.

“It makes me miss him,” he adds.

Further down the stairs, he looks out over the atrium with the Great Tree of Peace that hangs from the ceiling like an impressive chandelier, under which the commemoration event had taken place months previously.

He didn’t realize until then that his father had literally been watching over the event.

Powless lives by his father’s teachings, and one of his father’s reminders rings especially loud:

“In order to know where you’re going, you have to know where you come from.”

Moving indigenous representation forward

Exiting the Skä•noñh Center, you are confronted by an exhibit of sports fandom and cowboy-vs-Indian-style Native American imagery — the room, with its ugly face of appropriation grinning against the stark white walls, sits in blunt contrast with the rest of the museum.

Seeing Powless, a lifelong advocate for deeper understanding of indigenous concepts, stand among the tacky American Indian paraphernalia, feels simply absurd. Could the strange reality of it be any more striking?

“Oh what, like this?” Powless jokes, posing for a photograph with a four-foot, red-faced LEGO figurine next to a sign stamped with the exhibit’s title, in all-caps, “Tonto Revisited: Indian Stereotypes.”

He takes the toy man’s stiff plastic hand in his own. “Hey buddy, how are you?” he says.

Humor was another of his father’s biggest reminders: “The definition of a good day is did you make somebody laugh today. So, who did you make laugh today?”

Despite the seriousness of his work, bringing laughter and joy into a space has always been instinctual for Powless. Judy Evans, the office manager who works one-on-one with him at SU, says there is rarely a day they don’t laugh together.

Powless is no stranger to mainstream native representations like those presented in the Tonto Revisited exhibit. His currently-in-progress PhD at Syracuse’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications focuses on indigenous narratives in major motion pictures.

“He’s passionate about movies,” Evans says. “He can recite lines from a movie even 30 years ago and the things he remembers, it just, it amazes me.”

Powless recalled an evening as a kid spent at a cousin’s party. Someone had found a copy of Windwalker (1981), a western that takes place before European contact and with all native people as its leads. He hasn’t forgotten watching the film with his family and community, all packed into the living room around the TV.

“That left a really big mark in me to see all those people excited to see that, and I knew that being on film at that level was important,” Powless says. “And I had value. Human value.”

Powless had heard stories of community members being cast as extras in various films. His parents, brother, and sister were in a movie about the Trail of Tears with Johnny Cash, and the Onondaga Nation served as a cultural consultant for Indian in the Cupboard (1995). So by the time he was in high school at Lafayette and a casting call for extras in Last of the Mohicans (1992) came to Onondaga, Powless knew he had to try out.

A 140-pound Powless showed up at the audition. When they told him to pose, his response was to flex as they took a Polaroid. To his surprise, that was it.

His mom and brother were cast, but he didn’t end up making the cut.

Powless did eventually make his way onto a filmset, when he became a co-producer for Crooked Arrows. He also co-produced the film’s accompanying documentary short “The Game of Life, Heart and Spirit of the Onondaga,” which highlights the cultural significance of lacrosse and was nominated for an Emmy in 2013.

“You talk to Neal Powless about lacrosse, you’re going to want to go play right after that conversation,” says Bob Carpenter, founder of Inside Lacrosse magazine.

When Carpenter was starting his new publication in 1996, Powless was one of his first interviews. Twenty years later, Powless was a clear choice for an interview in Carpenter’s first feature length lacrosse documentary. Powless then began to help Carpenter as a cultural consultant, and eventually came onto the film as co-producer last year.

Carpenter still remembers his first time talking to Powless in 1996. Then, Carpenter was a college player obsessed with lacrosse as a fun, hard-hitting sport that was all about winning. But as Powless began to reveal to him, for the Haudenosaunee it is so much more.

Their documentary, tentatively titled Second Growth, takes a deep dive into the relationship between the modern major-league sport and its native origins. What had started as Carpenter’s vision of a Ken Burns-style documentary about the lacrosse stick evolved as he interviewed more and more members of the Native American lacrosse community.

“It became apparent that there’s a lot more story that needed to be told,” Carpenter says.

Empowerment, inclusion, and facing the culture gap

Today, Powless coaches lacrosse for the Orange, but not the Orange that Syracuse fans might expect.

In a remarkable fulfillment of the Two Row Treaty made between their two nations 400 years earlier, Powless has served as head coach of the Netherlands Box Lacrosse team since 2014. His coaching philosophy is to share a few core lessons of the sport, but let the Dutch team interpret how their country will play rather than import an exact blueprint from the game’s Haudenosaunee origins.

“In one row is a ship with our White Brothers’ ways; in the other a canoe with our ways,” the treaty says. “Each will travel down the river of life side by side. Neither will attempt to steer the other’s vessel.”

At Tsha’ Hoñnoñyeñdakwha, the Onondaga Arena, and Tsha’ Thoñ’nhes, the Onondaga Fieldhouse, the symbolism of the Two Row is embedded in the architecture of the buildings themselves. A subtle motif of parallel white lines runs through the stones for the entire perimeter of each structure. At the arena, two lines of cobalt-purple stones cement the image of the wampum belt into the structure’s exterior wall.

But an understanding of how to live by this message of two non-interfering worlds is not always so clear-cut.

For instance, Powless was of the first generation of students to enter the Onondaga Nation School while his own culture and language were part of the curriculum.

Nancy Powless, Neal’s sister who is 19 years older, has taught elementary students at the Nation School for 40 years. When she was a student there, it was conducted like a boarding school: they pledged allegiance to the flag, they sang traditional American songs, they learned Spanish as a second language — none of the teachers were native.

“It was just a brown school learning how to be white,” she says.

When the time came to transition from the Nation School (which at the time only went through sixth grade) to the Lafayette school system, she felt lost. Teachers and peers didn’t seem to understand her. She often felt overlooked, that quiet native girl in the back of the room.

Once she graduated, she knew she wanted to teach. She never wanted any kids to feel the same way she felt. At the same time in the ’70s, her community decided the previous system wasn’t what they wanted for their kids either.

For the Powlesses, it comes back to what their father and grandfather and other Haudenosaunee elders would always say: It doesn’t matter where you go, as long as you know who you are and where you came from. It’s all a part of the growing process.

“Pride of country is very ingrained in our teachings within the Longhouse and knowing our place,” she says. “You can move within both cultures and be OK because you’re comfortable with who you are and you know who you are, so it’s OK for you to be in a situation where there are no other native people there.”

The majority of what Powless sees in his daily life and work is different than what he sees in the mirror.

“But does that minimize my own experience or anyone else’s?” he asks.

Working on Crooked Arrows was an opportunity for Powless to engage in an environment that looked and felt like him. His community felt it too: when Powless sent out a message for help, five busloads of Haudenosaunee people answered the call and came to Boston for a weekend to be extras in the film.

Powless tells the story of one young native girl, who before that weekend was ashamed of her culture to the point that she told others she was not indigenous, but Italian. But after engaging with the proud native people working on the project, Powless says, she told her mother she would never again pretend to be someone she wasn’t.

“If I can make a film that gets one person to feel that way who’s indigenous, then that’s a success,” Powless says. “And if there’s one other non-native person who can engage in a film that I’ve made that then is willing to look at their own self-exploration and gain value in that space, that’s a success.”

Overcoming ego and meditating when it matters most

“I can’t tell you how many times I thought, ‘if only there were 10 of me,’ and then literally have to talk myself out of that thought in the middle of a game.”

He goes through his train of thought of one of those frustrated moments: But then five of me would have to learn how to play the same thing, but the mirror image. And we wouldn’t be great at defense, so some of them would have to learn defense. Maybe just three of me, then. No, still too many. Maybe two? On second thought, we’d make a ton of mistakes some games if there were a bunch of me. OK, just go do what you need, all you control is you, so go do it.

Powless laughed to think of himself performing that logical feat while out on the field.

“But we have to have that thoughtfulness in the heat of battle to be able to shift that and change that thinking,” Powless says.

In his role as University Ombuds, Powless helps members of the SU community engage in that same thoughtfulness in the heat of their own conflicts. His job is to act as a sounding board, to provide a safe space where every voice has value, where conversation can begin, where room for growth is made.

At the same time that mainstream society has only recently begun to accept indigenous land acknowledgments as a trend — a society in which SU for only four years of its 150-year history has officially recognized with respect the Onondaga Nation, firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee, the indigenous people on whose ancestral lands Syracuse University now stands — Powless has had a lifetime of experience recognizing and listening to the voice of dominant culture.

Now, as those voices respond to the call to listen to, acknowledge, and teach about minority voices, what will that diversity training look like?

When and how do we take ownership for past injustice, embrace the national stage, and step into our shared history as a university and as an international society?

Could you imagine incoming first-years at SU not just hearing a land acknowledgment at convocation, not just scratching the surface of conversations on identity in a multi-week seminar, but rather feeling the history of this land through a collective activity like the Witness to Injustice blanket exercise? And for our community to be the first university in the U.S. to do so?

Powless can.

“Right or wrong, good or bad, they’re going to hear a perspective of the truth that they probably haven’t heard before,” he says. “And that’s probably a good thing, because their first introduction to the university will be:

“What you understand to be truth is one version of the truth; here’s another version of the truth; here’s another lens. Let’s open our eyes and our hearts to hear each other’s voices.”