How the “Great Resignation” is affecting graduating college seniors

The “Great Resignation” affecting college seniors

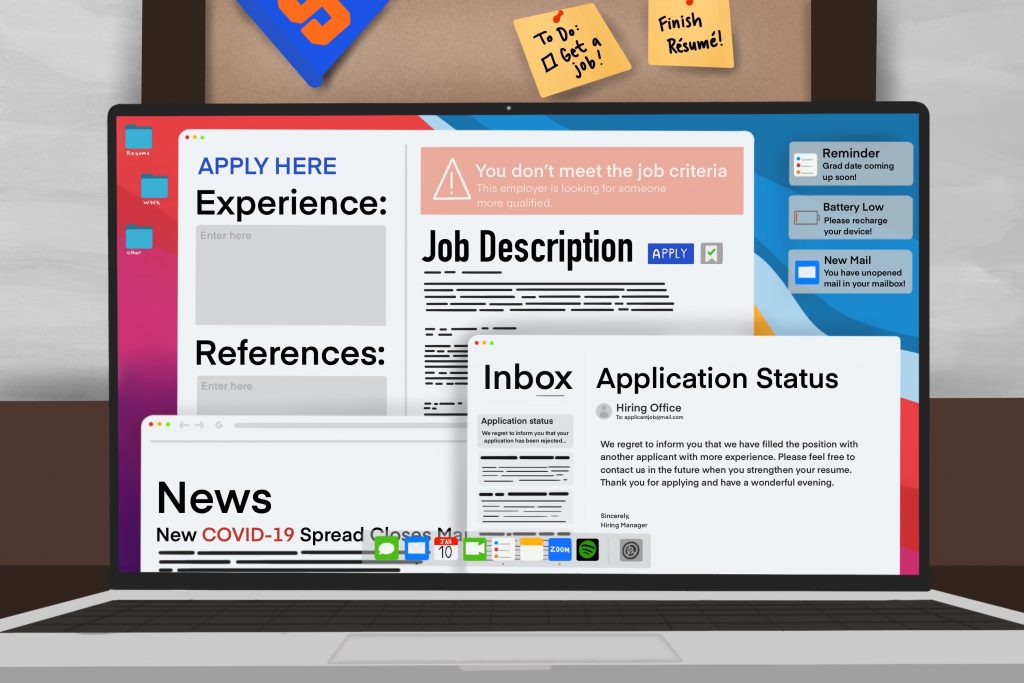

Michaela Varvis stared at her computer screen with anticipation. She quickly glanced at the time and taped the reload button on her browser. Nervously picking at her nail polish, she reread the words “please wait for the host to start this meeting.”

This was her final interview, the one that determined if she got the position or not. She sighed with relief when the loading sign started to spin, notifying her that the meeting was starting.

The call was quick and just the news Varvis was hoping to hear, she got her first summer internship.

Going into her freshman year of college, Varvis already had a four-year plan. Ideally, she would gain experience from on-campus organizations freshman and sophomore year, build up her resume, get an internship junior year and have a job lined up by the end of her senior year. But when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Varvis’ straight-forward plan no longer felt feasible.

Due to two years of global lockdown, Varvis spent almost the entire first half of her undergraduate career working remotely, with a majority of that time spent off campus at her home in La Habra, California.

The spring of her junior year was her first “normal” semester, sans masks and back in person, forcing her to speed up her timeline with no solid, in-person experience.

Varvis said she remembers the pressure she felt coming out of the pandemic straight into her final years of college.

“I remember just being so stressed because I had no idea how I was going to find an internship, let alone a job, without having gotten the experience companies were looking for in applicants. When I got the remote offer, I just took it.” Varvis said.

When the Syracuse University advertising senior entered her last semester in December 2022, she laughed at the irony of a global pandemic expanding her post-graduate opportunities.

Varvis, along with many other graduating seniors, are facing a new workforce that is dealing with the effects of what some business leaders like to call the “Great Resignation,” a phenomenon used to describe the mass exodus of workers during the pandemic.

This large-scale quitting trend has shifted the power dynamic between young prospective candidates who now have a much larger array of options and hiring companies who need employees quickly.

During the height of COVID-19, it was reported that over 4.5 million Americans quit their jobs during the Great Resignation. According to The Washington Post, many people are still following this pattern with a resignation rate of 4.1 million leading into September of 2022.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor found that just before the pandemic, the unemployment rate was 3.5%, but by the peak of the Great Resignation in April 2020, the rate had quadrupled and reached 14.7%.

According to a Pew Research Center survey, some of the top reasons Americans left their jobs were low pay, a lack of advancement opportunities and feeling disrespected at work.

“You want to feel like a human, so it’s a little bit daunting to enter a situation like that.” Varvis said.

While the decisions that led to this dispersal look different, the results have been the same. A plethora of job opportunities lowered competition between applicants and is giving graduating Gen Z students a newfound sense of confidence, while employers feel mounting pressure to impress this wave of self-assured potential newcomers.

Bridget Lichtinger, the assistant director of the Newhouse School’s Career Development Center, explained that students should feel at an advantage and should be, “for lack of a better term, picky” when it comes to choosing a job.

Lichtinger said that coming out of the pandemic, students understand that the job market is extremely favorable to them and much less competitive. The numbers from the pandemic revealed companies’ inability to keep employees, whether that was due to a lack of respect or low pay, and businesses are now facing the consequences of their actions.

As a result, graduating seniors are now taking advantage of this shift in conventional workforce dynamics.

The traditional job hunt process has been reliant on the fact that applicants are in a position to impress recruiters. Prospective candidates would apply, interview and then hopefully get hired. Applicant pools consisted of nervous college seniors and graduates, hoping to gain at least one job offer. But the age-old formula has now shifted.

Companies are now scrambling to impress and maintain students who view themselves as strong assets, creating an unforeseen power imbalance.

Seamus Kirst, a freelance writer who was part of the Great Resignation himself, was excited for this new movement.

“I think [the power dynamic shift] is such a good thing. This attitude of ‘you should be so lucky to have a job,’ is such a crappy environment for workers. I’m really optimistic in certain ways because I do feel like there is a shift with workers feeling more emboldened to stand up for themselves.” Kirst said.

For Varvis, knowing that she had the ability to be more guarded and thoughtful with the companies she considered, gave her a newfound sense of confidence in asking for transparency from recruiters.

“I know there’s a lot more opportunities, so it just all comes down to finding a good company that actually cares about me as a person.” Varvis said.

From companies’ perspectives, the self-assertiveness among Gen Z applicants is evident.

Natasha Stough, national recruiter for a major accounting firm, said she has seen a strong increase in self-assurance among students when they approach job offers and conversations with her and her team.

Stough said she thinks the higher confidence rates suggest stronger applicants and refers to the Great Resignation as a “perfect storm of opportunities,” creating a strong job market. She noticed her own company becoming more responsive to the needs of current and prospective employees.

As for the pandemic’s influence on the Great Resignation, Kirst said he believes that its effects are multilayered.

“I think it changed norms on a mass scale, and then changed values on an individual scale,” Kirst said.

He explained how, over time, the strong sense of mutual loyalty between employers and employees completely dissolved. Workplaces that were once generous in handing out pensions, bonuses and advancement opportunities eventually stopped, creating a new environment where people became more transitory with their jobs.

“When things started going remote, I feel like there was a newfound sense of distrust between employers and employees. Employers started overly checking in in a way that came across as infantilizing. COVID was very emotionally stressful on everyone, and I think the pandemic just shook up this feeling of deep rooted distrust, ” Kirst said.

For him, and so many others, the pandemic and remote working brought to light feelings of disloyalty when employees started feeling as though the companies they worked for were not being sensitive in the ways that they should’ve been during the height of COVID-19.

Despite remote working being a stimulant for employer-employee distrust, many Gen Z students are actually favoring virtual opportunities.

“Since COVID, there’s been more remote working opportunities which has been really nice because before, I was limited to in-person jobs close to home, but now I can look at positions in New York or other major cities without actually having to move out of my hometown and away from my friends and family.” Varvis said.

Caroline Casey, a recent SU public relations graduate, said that finding a remote position made the most sense when it came to her housing.

“I think that right now, I’m going to get a remote opportunity or at least go hybrid, because that way I can still think about where I want to end up living and not fully commit or have to start paying for another lease or apartment yet.” Casey said.

Lane Garnett, a recruitment manager at a major credit card company, said his team had received statistics that revealed many student candidates prefer hybrid work opportunities at their discretion.

They said they found that 56.1% of entry-level contenders wanted a hybrid format based on personal preference, 21.5% wanted hybrid based on company distinction, 11.6% wanted fully in-person and 10.7% wanted fully remote.

The shift in attitudes regarding remote working are apparent in questions applicants are asking recruiters. Stough said she thinks most prominent questions regarding work-life balance and mental health intertwine with Gen Z applicants’ desire to work from home.

As for questions about pay and monetary benefits, Stough said she understands the concern.

“With the softening economy, it makes sense that those are the questions being asked.” Stough said.

With the combination of debt focus, preferred remote working and an increased sense of confidence, many Gen Z applicants said they feel united in their preparation to both enter and change the professional environment.

As of December 2022, the unemployment rate has steadily fallen and is now resting at 3.7%, suggesting that people who quit their jobs have been able to find new positions since COVID-19.

The unemployment rate being so close to pre-pandemic numbers seems to indicate that the employment cycle has re-stabilized and companies are hiring at a typical rate again.

Not only are students expanding their job searches and feeling higher confidence, companies are also easing back to hiring pre-pandemic numbers, creating space for even more opportunities.

The Great Resignation was both a catalyst for the unexpected power dynamic transfer and a signifier of, hopefully, long lasting change. Both recruiters and students are quickly adjusting to this new professional landscape, creating an unpredictable workforce.