Why doesn’t Syracuse University pay Otto the Oranges?

Why doesn’t Syracuse University pay Otto the Oranges?

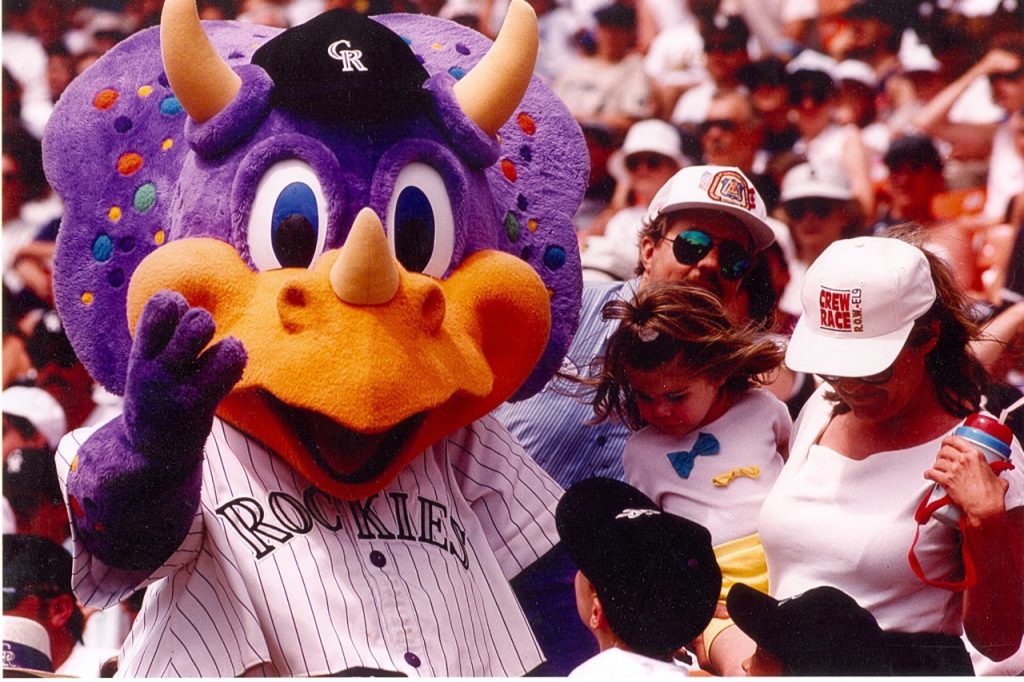

Marne Brown wore her best outfit for her debut on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon”: Orange and blue sneakers, navy blue tracksuit pants with a white stripe running down the side, and her oversized Otto the Orange mascot head. A Nike Syracuse University cap — discolored from years of student perspiration — completed the look. At 5 feet 7 inches tall, Brown fits the narrow height parameters to become one of the students bringing the beloved Otto persona to life.

“From Syracuse University, Otto the Orange, everyone!” Fallon announced. That’s Brown’s cue: She burst onto the stage, repeatedly high-tenning Fallon. But almost as soon as the moment began, it faded. She’d return to campus full of memories — none of which she could share with friends, nor did her role promoting SU on NBC benefit her bank account. At SU, Otto is volunteer service, not a job.

The clandestine world of mascots is much like the Batcave where the Caped Crusader resides, or so a jovial mascot assistant said. The process of becoming Otto is a safely guarded secret. At SU, all Brown could say about the process is that after an initial email, potential Ottos meet with the coach of the mascot program, Julie Walas, and proceed to tryouts. Throughout this covert operation, Brown recalls phoning her mother in earnest, assuring her that she messed up in the “silly process.” Meanwhile, the Otto program welcomed Brown into their ranks, and she learned two lessons in rapid succession.

Lesson one: Don’t wear a headband under the Otto suit.

Brown often tames her thick, frizzy coils of brown hair with a bandana or headband, as she did on her first gameday as Otto. Within minutes of her entrance into the Carrier Dome for a women’s basketball game, the headband slid down, obscuring her already narrow field of vision. Brown ran into a closet for a speedy fix, only to realize how disorienting the costume could be. Lesson two: Watch out for small children trying to nestle their way under Otto for a hug.

“Otto is definitely more about the personality,” Brown says. “That’s a huge thing that we focus on in recruitment, is just like the personality behind the suit, but also the personality behind the people who join the team.”

Brown and her fellow Ottos are Division I student-athletes, but the yearly commitment far exceeds that of any other team. The 10- to-12-student team remains on campus for 360 days of the year — back home usually from December 22–27. Despite all the revenue that Otto generates and the smiles they create, student Ottos do not receive a stipend or official payment, nor can they apply for select cheer team scholarships – which range from $1,000 to $1,500 – that might otherwise mitigate the weekly time commitment until at least two years of Otto’ing. For the sacrifice of time and energy, SU’s investment in the students behind Otto could be improved to make the program more accessible.

“The embodiment of the mascot to some degree becomes a connection to a university, to a city,” says Andrew Billings, the Ronald Reagan chair of broadcasting at the University of Alabama. “To the point that even if you’re not a fan of that given team or that given sport, the thing offered at that university, you still identify with the mascot itself.”

Colleges allocate funds in divergent ways, and in many private institutions, this information is unavailable to the public. A modest cross section of schools considered by SU to be peer institutions — a grouping of schools often compared for retention and graduation rates — discussed their own mascot programs. These included the University of Miami, University of Connecticut, Pennsylvania State University, Boston University and Marquette University. Beyond peer institutions, Georgia Institute of Technology, Clemson University and the University of Virginia, provided information online.

Though seven of eight offer some form of compensation — a scholarship, stipend or hourly rate — program structures within this selection of schools run the gamut. At Miami, associate director of event experience and marketing Will LaRossa says all students are paid a rate based on their seniority for all sports games and special events like weddings. A Sebastian the Ibis mascot jersey hangs behind him, a remnant from his own tenure as the avian mascot. He’s blasé about the mascot program, as if he doesn’t want to fully admit that a fluffy, oversized bird bedecked in bling meant more than just the football games.

During his junior year of college as Sebastian, the mascot program coordinator further incentivized students to don the suit for hours. Instead of the current flat rate received, students could now be paid per event. “Sebastian is the face of the school,” LaRossa says. “We want to make sure we’re attracting the best people to be in the suit that we can have that are the best representation of the university. So part of that is incentivizing through pay, and anytime that they work, they get paid.”

This shift away from stipend programs toward a tiered payment system aligns with Marquette, Clemson and Boston University’s respective programs. Of these, only Clemson releases rates: $75 per hour for weddings, $50 for university and private events. Meanwhile, Georgia Tech and Penn State offer a scholarship for mascot students. Penn State stands out as the only program from the list that has one student as the school’s Nittany Lion. Curtis White, the spirit director for Penn State, says that the student receives a full in-state tuition grant as they bring the spirit of Penn State to over 300 events annually. After being with the school for 23 years, White says he’s noticed an increased involvement with the mascot and cheerleading squad at football and basketball games alike.

“I wouldn’t call [SU’s mascot program] lagging behind,” says SU’s executive senior associate athletic director, Sue Edson. “It’s choosing how to use your resources and identifying your priorities. Every school has the right to do that.” For reference, Edson adds Syracuse spent $130 million on the Carrier Dome renovations and that no one would compare this decision with Cornell’s decision not to upgrade their field in 20 years. “I don’t think that’s a fair comparison either,” Edson says. But is it fair to allocate $130 million to upgrade the Dome and not pay Otto, one of its main ticket sellers?

Her point sashays around a larger issue: Colleges and universities don’t have enough dialogue between one another surrounding athletics. Even less so in the underworld of mascotting. Brian Morgan, Marquette’s associate athletic director, and Brian Begley, director of game presentation and fan experience, were shocked to hear SU and other mascot programs require mandatory workout sessions. “Oh, that’s a great idea, we should do that,” Morgan says, glancing back towards Begley with a knowing look. The extent of their conversations with other schools usually entails methods for increasing football attendance, Morgan says. He calls the mascot “critical” to the success of Marquette athletics.

Joby Giacalone, a professional mascot, says nobody understands the value of a true entertaining mascot. After 40 years traversing the amateur, collegiate and professional mascotting arenas, he learned everyone organizes their programs differently. “Frankly, none of them are wrong,” he says. “They all choose to place value in different places. There are some major league teams that are paying their mascot performers over $100,000 a year, and there are some that are paying them $15 an hour.”

“I’m not saying one is wrong, and one is right,” he continues. “I would say I’m not gonna go work for the $15 an hour one.”

Giacalone served as Lenoir-Rhyne University’s mascot while he was a student in the 1980s, during what he refers to as the “golden age and real start of mascotting.” It was a precursor to his eventual role as Dinger the Dino, the inaugural mascot for MLB’s Colorado Rockies. But back at Giacalone’s alma mater, the idea of compensation never crossed his mind. When he returned to Lenoir-Rhyne train the new performers, he learned that, with an estimated 1,700 undergraduates, student mascots were now paid $1,000 per year.

Of the nine schools surveyed, SU and UConn both stand out as the only schools without an official compensation system. Although, that doesn’t mean the students go without perks typical of a DI athlete. Brown and her coach Walas say that student mascots benefit from access to exclusive SU gear, a personal trainer, academic tutors, upgraded dining options and per diem, which Walas explains is a daily stipend for meals when Otto travels for away games. Plane fare is also covered by the university, a customary protocol with other sports teams. Whenever former Ottos can, they will host and “spoil” current students in New York City or Washington D.C. for holiday parties and away games like the recent one against Georgetown. “Are they excessively and abundantly showered in scholarship? No,” Walas says. “But I think that the students who come are kind of doing this because it’s so cool. Their identity is kept secret and they’re doing it for the greater good of the university.”

According to SU’s athletic website, Otto makes more than 700 appearances each year at both university events and personal or corporate events. Inviting Otto can cost anywhere from $100 to $500, via the site’s suggested payment plans. And unlike the majority of its peers, these fees cover the ongoing operations of the SU Spirit Squad. Not a cent goes to the person bringing the bubbly antics of Otto to life.

But Walas is right. The mascot program attracts students unfazed at the prospect of wearing each other’s sweat, cramming for exams and hiding a Dome-sized secret. “The team is probably why we didn’t care to get paid,” says Michael Lehr, a former Otto the Orange from 2016 to 2018. “You hear the story of somebody that day who went to a hospital, or got to work a buzzer-beater basketball game, and I feel like that’s almost your currency — the magic and being a part of something that’s global honestly.” Though he wouldn’t have turned down a scholarship or payment program.

For all of the derisive articles written about Otto the Orange — calling the costume “moldy,” the concept “nonsensical” and general ridicule over the “silly plush toy” — the Otto mascot program is vital, not only as a spirit generator, but also as a walking billboard for SU. The history leading up to today’s cuddly, citrus-themed mascot involves a soured joke, offensive caricatures and trolls.

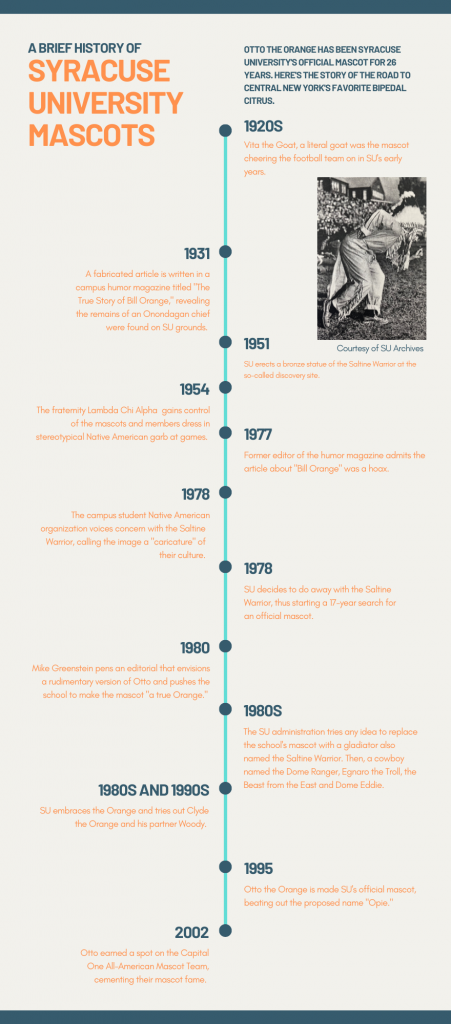

In 1931 — less than a decade after Syracuse’s inaugural mascot, an actual goat named Vita, made its leave — the origins of a new mascot emerged in the pages of a student publication. Syracuse’s premier humor magazine, the Syracuse Orange Peel, published a fictionalized story titled “The True Story of Bill Orange,” which the campus believed without question. Within the piece, they claimed that an archeological dig conducted on campus unearthed the remains of a 16th-century Onondagan Native American chief named “O-gee-ke-da Ho-schen-e-ga-da.” The magazine said it translated to “Saltine Warrior.” Soon after, the university adopted the Saltine Warrior as SU’s mascot.

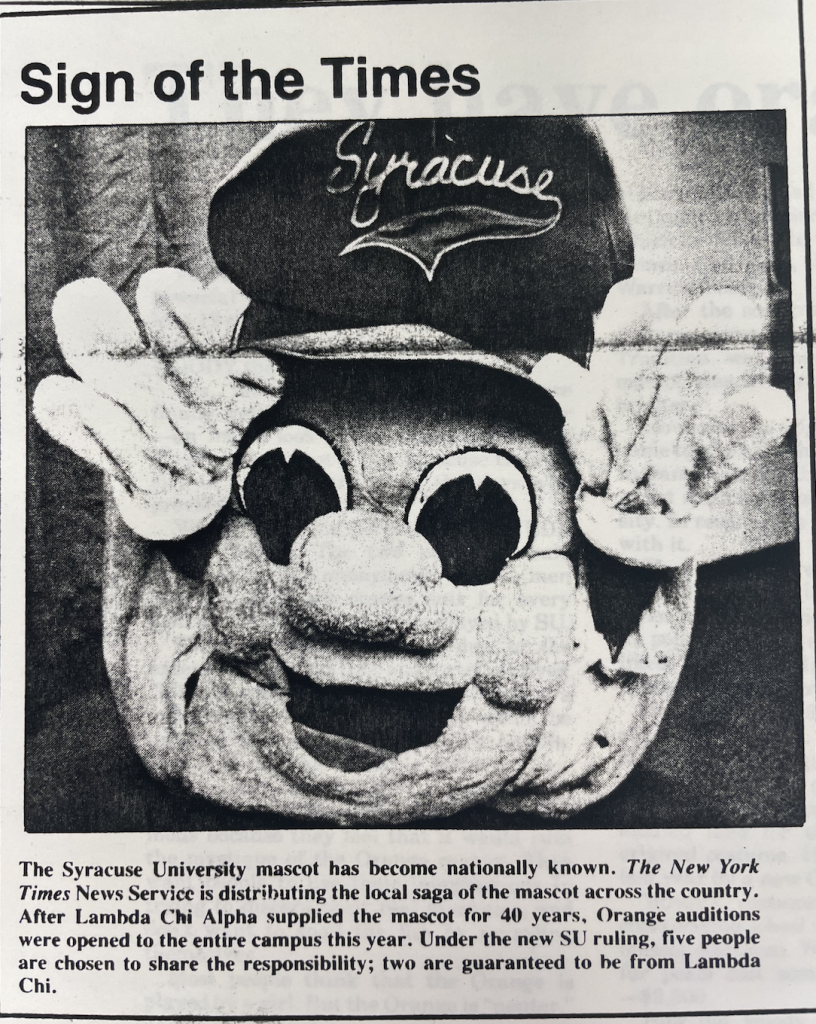

By then though, control of the mascot fell to brothers in the Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity, as stipulated in their charter. 1954 marked the first year members painted their faces, wore buckskin pants and an intricate feathered headdress as the Salt City Warrior.

Decades passed with the Saltine Warrior as the symbol of the university, until in 1977, the former editor of the Orange Peel admitted to the whole fabrication of “Chief Bill Orange.” At the same time the Native American campus organization Onkwehonweneha began protesting the use of the Saltine Warrior. A 1978 editorial on behalf of the organization to The Daily Orange newspaper reads, “No self-respecting people/persons would consent to be depicted as a painted, feathered, war-crazed, half-naked fool for the stated purpose of stirring the spirit of patrons at various athletic contests.”

SU’s campus became embroiled in a months-long debate over the continued use of the mascot that concluded — much to the chagrin of alumni — with the retiring of the Saltine Warrior. “Tradition be damned seems to be the prevailing attitude,” alumnus Paul Brooks later wrote in a March 10, 1989, editorial. “It began with, and is best exemplified by, the elimination of the Saltine Warrior, a concession to the liberals among us who felt Native Americans were offended.

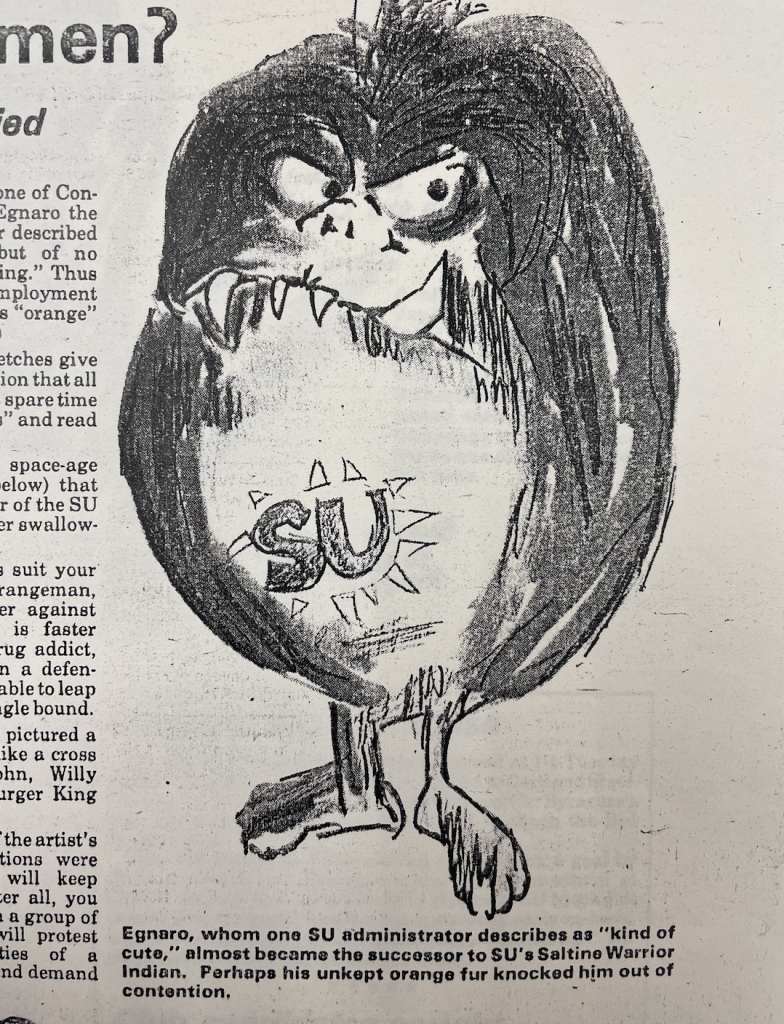

For the next 17 years, the campus went without an official mascot. In that span, the administration tried to replace the Saltine Warrior with a Roman gladiator. Then came the Dome Ranger, SU’s take on a cowboy, Egnaro the Troll, the Beast from the East — described as a mix between a monster and insect — and finally a guy dressed in sunglasses and a frizzy orange wig and jumpsuit known as Dome Eddie.

None of these eclectic misfits lasted long. But an April 1980, editorial by Mike Greenstein may have pushed SU to go for the low-hanging fruit. “Make the SU mascot a true Orange. After all, that’s the team’s nickname, isn’t it?” Greenstein wrote. “Put him in orange sweatpants and sneakers and insert him inside a five-foot, foam rubber orange ‘Nerf Ball.’ Put a hat on the top and let the guy run around like a crazy man and bounce off people.”

Though still unofficial, SU brought Greenstein’s vision to life as Clyde the Orange. Together, Clyde, alongside his partner Woody, entertained throngs of fans at the games. A letter from the then-director of SU Archives and records management, Ed Galvin, revealed a third costume was in the works. At a cheerleading camp in Tennessee, members of the team decided between two names: Opie and Otto. Fear of opposing crowds jeering “Dopey Opie” led them to go with Otto, and on Dec. 5, 1995, the Syracuse Herald-Journal declared the birth of Otto the Orange, the gender-neutral fruit. Despite initial questions regarding Otto’s longevity, they are nearing 25 official years as SU’s mascot, though not without some cosmetic updates.

Across hundreds of newspaper clippings and digital scans encompassing decades of mascot history, there were only two mentions of student compensation. In 2002, Otto earned a spot on the Capital One All-America Mascot Team, a distinction garnering the SU athletic department a $5,000 scholarship. Then, a feature on Nick Natario, a 2006 Otto, said during a commercial shoot the company paid him $50 per day. With most of SU’s mascot history manned by a fraternity, the issue of compensation remained a moot point. Somewhere between Clyde and Otto, the program legitimized into a brand ambassador marketing machine for the university. Under Walas’s guidance, the program further established itself on an idea of selfless volunteerism. 26 years later, legitimate compensation has yet to follow.

Memories of antics in the Otto suit have always been sufficient payment for Michael Lehr. Meeting President Joe Biden after the men’s basketball Final Four game in 2016. Watching hundreds of children run to their new parents in The Oncenter on National Adoption Day. Lehr’s fondest memory occurred at the unlikeliest of places: The Sisters of St. Francis convent in Syracuse, New York. Known for their dedicated Syracuse basketball fandom, the nuns waved orange flags, screaming with excitement as Otto ran around the convent, their signature airplane arms splayed outward. One of the nuns watching the spectacle was Lehr’s great-aunt, Sister Alma, 94.

“At one point, my aunt grabs Otto by the brim of the hat, looks Otto in the eyes — which is me in the suit — and says, ‘Otto, my nephew goes to SU. His name’s Michael Lehr. You have to give him a big hug next time you see him,’” Lehr says. “The whole thing was just insane.”

Fast forward to Lehr’s senior year, when the Ottos reveal their identity to the home crowd in a spectacle of splendor, and Lehr was able to tell his aunt Alma that he was the Otto that

visited the convent on that fateful day. Lehr credits his mascot coach Walas for making these unforgettable moments happen and letting Otto run wild. Because once Otto suits up, the plush bipedal citrus never ceases: surprising a snoozing event worker, waving to the marching band, jamming out with the bewildered saxophonist, heel-clicking, meeting at center court, posing for a selfie with customers in the gift shop purchasing a pint-sized version of Otto. “It’s remarkable how much I lose Otto,” Walas says. At every turn, Otto’s ridiculous presence ignites excitement.

Similar to so many other students interested in becoming Otto “the sneaky athlete,” Walas went to tryouts “on a whim” during her junior year as an undergraduate at SU. The experience fueled her to later accept an offer to become the unofficial, part-time mascot coach, which she’s done for 14 years. However, during her first few years, SU athletics told her they were unable to pay her even a part-time salary.

Brown, while she says the community that she found through Otto to be invaluable, wishes the program could offer some financial support. She works a part-time job on top of her 10- to-12-hour Otto commitments. “An opportunity for scholarship could have been super helpful,” Brown says. “Especially for the people that maybe were more busy than me that couldn’t do a part time job.”

Students can’t consider the demanding, unpaid role of Otto a viable option, unless they also secure a work study position or additional part-time job. Only those with financial means have access to the behind-the-scenes life of Otto.

With the limited existing scholarships that extend to the Spirit Squad as well, relying on receiving one is not the same as a payment system like BU, Clemson or Miami. Walas says she would pursue many other avenues before a universal scholarship, but doesn’t propose any alternatives. Other coaches and mascot coordinators feared an incentive program would attract students with less passion — but the opposite has been true. LaRossa of Miami says that since the implementation of the payment system, incoming students are more engaged with the program and willing to go to more events.

Otto the Orange is for everyone. Students, faculty, staff, the surrounding community and even the jeering away-team’s fans. It’s a sentiment every former Otto echoed. But, without a compensation program that goes beyond payment in the Otto experience, the opportunity to be Otto the Orange isn’t accessible to everyone. It’s as simple as that.