Why we need to think beyond supermarkets when dealing with food deserts

Dealing with food deserts

On a chilly, wet November afternoon, residents of Syracuse’s Near Westside wait in a vacant parking lot to receive a box a free food from the Central New York Food Bank. Murmurs in Spanish, English, and other languages fill the air as residents trickle in from one of the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Many of those waiting demonstrate the struggles they’ve endured. Some are missing limbs. Others lack teeth. Some make their way to the front in wheelchairs and with canes. Others shield their children from the bitter winds under blankets. Their clothes appear well worn and tattered in places, and they wear their exhaustion and the frigid temperature on their faces in furrowed brows, squints, and blank stares. Everyone seems eager to get their box and go home.

A month ago, this parking lot accommodated customers of the Nojaim Brothers Supermarket, the community’s only full-service grocery store. Israel Gonzalez, 67, waits in line next to his tricycle with a shopping cart attached to the top. The cart features a rigged steering wheel with two ropes so he can steer from behind. He keeps a Kermit the Frog stuffed animal in the cart for good luck and says this device helps him carry his groceries and belongings to his home in the James Geddes Public Housing Complex. Gonzalez relied on the Nojaim Brothers Supermarket to provide the Hispanic food products he and his wife prefer. He says he has been suffering since the closing. An electric wheelchair serves as Gonzalez’s only mode of transportation, and without a grocery store in his immediate vicinity, he must travel between one and three miles to the next nearest store.

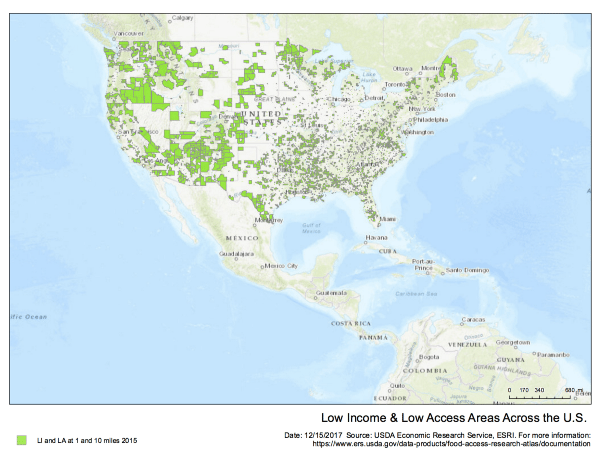

At more than one mile from a supermarket, Gonzalez resides in what is known as a food desert. The USDA defines urban areas as food deserts when 500 people or 33 percent of the population lives more than one mile from a supermarket or large grocery store. At a surface level, food deserts may seem simply as communities that lack adequate access to grocery stores, which suggests adding stores would serve as a solution. However, when evaluating how food deserts manifest across America, factors such as race, income, distance to stores, and health play critical roles and help illuminate important factors beyond the existence of stores. “Questions of food insecurity and hunger are economic questions,” says Evan Weissman, an assistant professor of food studies at Syracuse University. “What that means is we’re not just asking why don’t people have enough food, we’re looking at why there is so much inequality in society and how that inequality is produced by the food system.” Resolving food deserts demands more than just adding grocery stores. In fact, food deserts are also associated with food affordability, the types of food and stores available, and how these factors correlate with consumer health — especially within low-income communities.

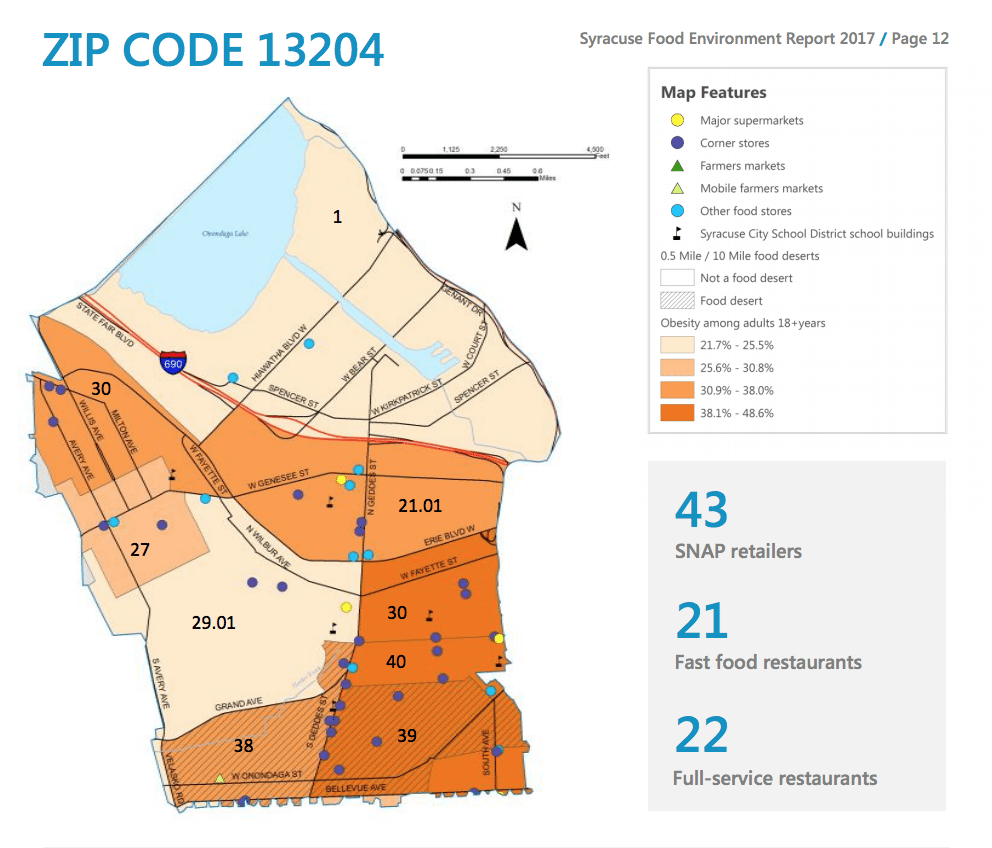

The USDA estimates that 54.4 million people in the U.S. live in low-income and low supermarket access tracts. For residents in the Near Westside neighborhood, the median household income is $28,220, and 40 percent live in poverty, according to food environment report from the Onondaga County Health Department. The report analyzed Syracuse’s nine zip codes and found the Near Westside and Southside to be the top two communities with the poorest health outcomes such as diabetes and obesity, the highest number of children living in poverty, and the least likely to have vehicle access. In addition, these two neighborhoods combined have more corner stores than any other area in the city with one store for every 573 residents. Corner stores typically offer less nutritious options and more processed food, and the surplus of these stores help explain the negative health consequences found in these neighborhoods.

Researchers seeking to resolve issues regarding food access explore questions such as what type of foods are offered, how the foods are marketed, and people’s abilities to adopt healthy dietary practices. “If you’re going build a supermarket — a healthy food source, that may not be enough. In addition to placement, there needs to be a very conscious effort to encourage people to buy the healthy food,” says Bonnie Ghosh-Dastidar, Ph.D., a senior statistician at the RAND Corporation. In 2011 Ghosh-Dastidar co-investigated a five-year study led by Tamara Dubowitz, of two predominantly African-American, low-income, food-desert neighborhoods in Pittsburgh — one neighborhood received a new grocery store, and the other did not.

The study sought to analyze the relationship among store distance, food prices, and obesity and revealed that distance to stores remained less significant than a store’s pricing and food display methods when it comes to measuring body mass index (BMI) and obesity rates. “If you put a supermarket in a food desert, shoppers may come, but whatever the individual characteristics are of the store may be just as important to drive what they’re buying,” says Ghosh-Dastidar. To illustrate that point, she points out that high-price stores such as Wegmans or Whole Foods and low-price stores such as ALDI or Price Rite do not vary in terms of the foods available. All those stores offer fruits, vegetables, and junk food. However, low-price stores market the junk food two-thirds of the time more than the high-price stores. “If you can change both the in-store marketing and the pricing, then that perhaps could have a far bigger impact on what people buy and put in their carts,” says Ghosh-Dastidar. Studies like these demonstrate that factors beyond simple access influence a healthy diet; however, this does not suggest that low-income communities do not need grocery stores in their neighborhood.

Unfortunately, for residents of the Near Westside, the likelihood of a new grocery store replacing Nojaim Brothers Supermarket is a long shot despite the needs of the neighborhood. The Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion and the Syracuse Housing Authority surveyed 57 Near Westside residents following the closing and found that more than half of those surveyed wanted a replacement in their neighborhood. Although a Price Rite opened on the Southside in October, only 49 percent of Near Westside residents were shopping there prior to Nojaim’s closing. Paul Nojaim, the owner of the supermarket, says he knows this neighborhood needs a full-service grocery store, but adds that due to the supply and demand, he was heading toward bankruptcy, which led him to close his family’s 98-year business.

To fill the food void creating by the store’s departure, Near Westside community members have been working on short-term solutions to relieve the neighborhood’s food-insecurity stress. Some projects include the mobile food pantries in Nojaim’s parking lot and the organization and distribution of a list of various places where residents can find free food. The November mobile food pantry supplied 120 boxes of fresh fruits and vegetables, bread products, yogurt, milk, and juice, which were donated from various retail firms like Wegmans and Trader Joe’s. “We want to provide something that prevents people from falling off the cliff into a crisis and hopefully be part of a long-term plan, but this is something that needed immediate action,” says Brian McManus, the CNY Food Bank Procurement Manager.

Alongside those connected to the CNY Food Bank was Leah Russell, a project coordinator for the Center for Court Innovation. Russell heads the resident-led Community Impact Team in the Near Westside and explained how her team typically works with criminal justice reform, but began to see the intersection between public safety and community health. “We need to be having that health conversation and talking about nutrition, talking about active living, and addressing the barriers that prevent people from having those livelihood opportunities,” says Russell. Since the closing of Nojaim’s, Russell and her team are attempting to influence healthy behavior changes in culturally appropriate and relevant ways within the community and find ways to make healthy food accessible in corner stores.

But those who support residents of the Near Westside aren’t the only organizations seeking to find food-access solutions. These issues also have attract attention and efforts on the national level. During the Obama Administration, the connection between obesity and unhealthy dietary practices drove Michelle Obama to launch her Let’s Move campaign to eliminate food deserts within seven years. In part of this campaign the Obama Administration also launched the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI), which provides financing opportunities to develop and equip grocery stores, corner stores, and farmers markets to sell healthy food in underserved communities.

The Reinvestment Fund serves as another organization that finances projects to improve low-income communities. In 2010 the organization expanded their research to Low Supermarket Access (LSA) in low-income communities and received funding from the U.S. Department of the Treasury Community Development Financial Intuitions Fund. “From a business model perspective, the economics of putting in a new store do not always make sense in some of these areas,” says Michael Norton, Reinvestment Fund’s Chief Policy Analyst. The LSA research conducted in 2014 found that in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, over half of LSA residents were low-income. The data also revealed LSA areas are steadily decreasing, but solely looking at the location of supermarkets overlooks the various components that lead to healthier lives, such as if a stores is culturally relevant to the community, offers appropriately priced goods, and promotes healthy foods.

In more recent news, the USDA in January 2017 announced a pilot that would allow Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants to purchase their groceries online. Currently there are seven retail firms participating, including Amazon and Dash’s Market in Buffalo. Online grocery ordering apps and websites have gained popularity in the U.S. and a 2017 report by the Food Marketing Institute and Nielson noted that 23 percent of American households currently purchase their groceries online; by 2025, they predict online spending could reach $100 billion in annual consumer sales.

Online grocery purchasing and delivery services possess the potential to help individuals who lack transportation to supermarkets or have mobile disabilities. However, these technologies do not represent solutions to influence healthy dietary practices in low-income neighborhoods. At the Georgia Institute of Technology, Carl DiSalvo, Ph.D., an associate professor in the school’s Digital Media Program, believes technology can act as an information platform, but it is not the all-end solution to food deserts. “At the end of the day, the problems are really systemic and the problems really end up having to do with policy and markets and trying to find solutions so that grocery stores don’t leave neighborhoods,” DiSalvo says. “That’s ultimately a problem that’s not going to be fixed with technology.” Similarly, Weissman points out that beyond attaining food, solutions must address questions about whether individuals live in a place with a kitchen that offers working utilities, clean water, and a stocked pantry with ingredients necessary for cooking, or even possess the correct utensils. “A comprehensive solution entails creating economic opportunity for all so that people can have the needed resources made available through job opportunities to appropriately feed themselves and their families,” Weissman says.

Back in Syracuse, residents of the Near Westside and those seeking to support them still work to develop comprehensive solutions but also remain focused on immediate, short-term projects. The CNY Food Bank returned to Nojaim’s parking lot this December. Announcements noted a 3:30 p.m. start, but Near Westside residents began lining up hours in advance. They know supplies are limited and that everyone in line might not receive a box. A boom box pumped the soothing sounds of bachata, a genre of music originating from the countryside and rural neighborhoods of Dominican Republic, into the crowd in an attempt to relax the cold and anxious residents. But the line had begun to lose its shape, and residents started to push to the front. Diane Hamilton, 72, approached the head of the line in her electric wheelchair, wearing giant, gold hoops and a paisley handkerchief. “Last time, the handicap were allowed to go first,” she says to a volunteer.

Representatives from the Food Bank packed the 150 boxes for this event, but residents will have to wait weeks before they have access to another round of this fresh (and healthy) food. Leah Russell, the project coordinator for the Center for Court Innovation, knows the fight for healthy food in her community requires a long-term commitment. Her team met with Syracuse’s front-running mayoral candidates to hear how they plan to tackle this issue and want to see changes in the near future. “There’s an element of speaking truth to power and showing up to meetings where decisions are made and resources are allocated,” Russell says. “We need people to know there are a lot of families over here, and we need access to healthy food because what we put in our bodies determines the health of our community.”