Uprooted and transplanted

Uprooted and transplanted

Snowflakes fall gently on Salt City Harvest Farm in Syracuse on a bracing March day. In the distance, almost indiscernible, raspberry and blackberry vines entwine themselves around a fence two-feet high. On one side of the fence, a snow-blanketed hops farm and a vineyard occupy five acres. On the other, the whitened land awaits the spring thaw when refugees will plant fresh vegetables and fruits. As they’ve done for the past three years, Somali farmers will plant corn, beans, and three-foot-long squash. Bhutanese and Nepali farmers will tend the marigold flowers lining the perimeter of the land’s subplots to ward off pests from their tomatoes, peppers, and mustard greens.

Manika Gautam is one such farmer in Syracuse. She lives in the Northside with her husband, her father-in-law and her three children — two minutes don’t pass without Ushan, her youngest, bawling for attention and chomping down with his few teeth on whatever comes his way, be it paper or pencil. Her father-in-law sits cross-legged on the floor, his back against a wall, keeping a wary eye on his grandson. Posters of Hindu gods and goddesses — Krishna, Ganapati, Durga and Lakshmi— are prominent on the walls, which are festooned with tiny Christmas lights, still twinkling at 3 in the afternoon. Just as prominent are the pictures of Gautam’s family from Nepal: her kids when they were younger, selfies with her husband, and Gautam with her in-laws as well as her sister’s family, smiling happily in front of a temple.

Originally Nepali and married to a Bhutanese refugee, 33-year-old Gautam used to live in the Morang district of Nepal. She grew up going to a government school where the curriculum was conducted all in Nepali — Nepali public schools conduct classes primarily in Nepali and English as a mode of instruction was offered only in private schools, according to World Education News + Reviews. She studied up to the 10th grade, after which she left school, spending her days on the family’s farm, selling their food in the market and making occasional trips to the border Nepal shares with India, hoping to secure more produce.

At the age of 27, she left Nepal — “many things are no good there,” she says, speaking of “many rapes and murders” — and arrived in Syracuse in 2013, with her husband and oldest daughter, Unisha, in tow. Her parents in law had already moved to the States when she moved. Today, the trips home to Nepal are few and far in between and she keeps up with what’s going on in her homeland by watching videos on Facebook and YouTube.

“I feel so sad,” she says about watching these videos. Though Gautam never personally encountered the problems that worried her so, she wanted to ensure a future free of crime and unrest for her family.

“Free to live,” she said through heavily accented broken English when asked why she left. “Free to work, better life and education for children. I’m thinking good life.”

Achieving the good life hasn’t been easy. The snowy Syracuse winters overwhelmed Gautam, who was used to living and farming in far more temperate conditions. She remembers her family and friends lending her jackets to help her through her first winter. She had no command of English.

“First time, I am afraid because there is so much snow and no English. That’s why I’m afraid, ‘what do I do?’” she remembers thinking.

She had two more children in the next five years, time that she also spent learning how to integrate and apply for U.S. citizenship. Deciding to work on her English, she enrolled in classes and that’s where she first learned about a farming opportunity for refugees like herself.

“My teacher said ‘anybody like farming?’ and I liked farming,” she says. “So that’s why I participate[d]. In my country, I am always farming.”

Gautam began farming through the Syracuse Refugee Agricultural Partnership Program (RAPP), a three-year $100,000 federal grant aimed at providing refugees a chance to farm and grow healthy, culture-specific produce to sell at markets and to provide their families with a reliable source of food. The RAPP three-year grant, first established in 2011 by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, served 14 farming projects in the U.S. In 2016, 15 more refugee-service organizations in ten states — Kentucky, New York, Hawaii, Rhode Island and Georgia, to name a few — across the country received this funding for the first time.

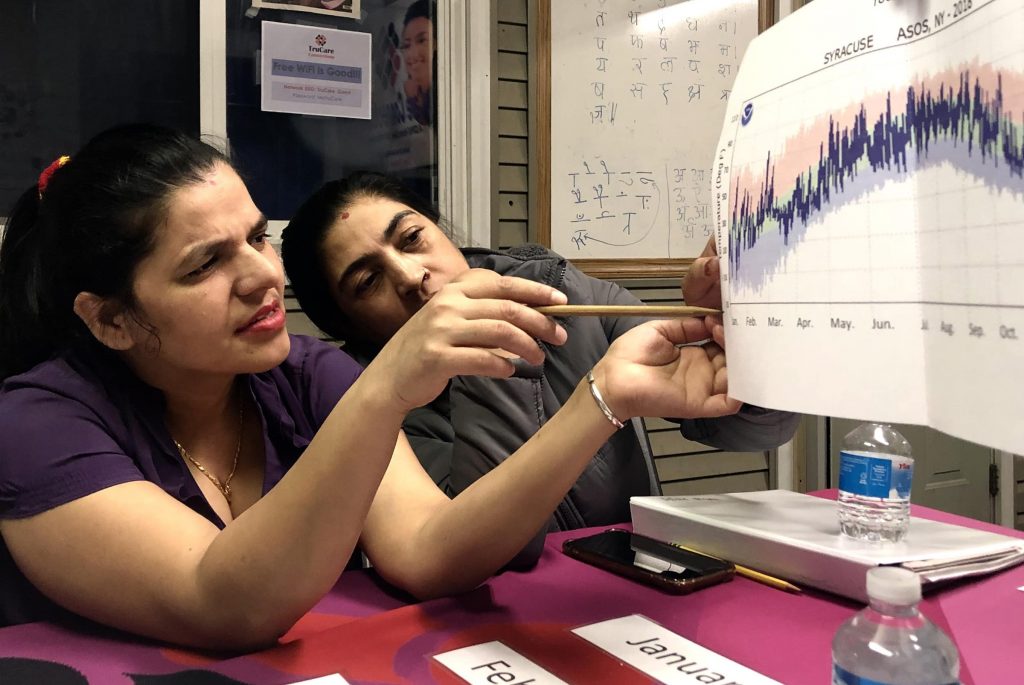

One of these organizations was Syracuse’s Refugee and Immigrant Self-Empowerment (RISE), which aims to provide employment, education and social support for refugees and immigrants in Onondaga County, NY. The Syracuse RAPP program, funded by the grant, takes participants through English, business and marketing classes, all the while educating refugees about seasons, irrigation and plant varieties and terminology specific to American farm production — one class, for instance, is devoted to teaching them which parts of the plant are connected with potassium, nitrogen and phosphorous production, respectively. The same class teaches them about planting like seeds in rows — “one bed, one family.”

“One of the challenges refugees face is that they come from much warmer climates than Syracuse and so they don’t really understand how the seasons change and what happens to the crops,” says Brandy Colebrook, the Syracuse RAPP coordinator. “So we have to explain to them that ‘this is what you need to plant at this time’ and that’s really a big thing with them.”

Each year, the farmers get a slightly bigger plot on which to grow their plants and by the end of the three years, the hope is that the farmers either have full-fledged businesses or simply a reliable means to feed their families and neighborhoods.

Gautam had visited Salt City Harvest Farm’s community garden in 2014, but began formally farming there in 2017 with 15 other refugees, armed with a little more bookkeeping, business knowledge, and English. In 2018, she planted rice, beans, cucumbers, tomatoes, spicy white radish and lentils, each of which was turned into dal, saag, curry and pickle. She calls spicy white radish moola, chuckling that “people no mostly like.” At the mention of cucumbers and tomatoes, Gautam’s second daughter Usha squeals in delight — they are among her favorite ingredients in the soups that her mother makes.

“All,” Gautam says quickly with a smile, when asked which of her Nepali dishes are favorites in the house.

Though Nepali homemade food still finds its mark, her kids all love “U.S. food” now, she says. Pasta is no stranger to Gautam’s kitchen.

Each year, over 70,000 refugees fleeing persecution take long flights across the world to the U.S. and emerge apprehensively into a world of paperwork, ESL classes and case workers. Refugees in America come from across cultures and countries — Somalia, Nepal, Bhutan, the Congo, Myanmar and Liberia, to name a few — but one thing tying a large portion of these refugees together is food and agriculture. For over a decade, farms and community gardens formally dedicated to refugee and immigrant agriculture have been mushrooming in states like California, Tennessee, Idaho and Ohio. The roots of refugee agriculture lie in a Tufts University initiative, the New Entry Sustainable Farming Project, to increase food security for multi-cultural farmers and help them grow food specific to their home countries. A 2013 survey by the Project noted that the farms served the needs of 5,700 beginning and aspiring farmers in Massachusetts, over half of whom were refugees or immigrants. These farms devote themselves to vegetables, grains and fruit grown in refugees’ home countries: bitter melons, okra and mustard greens abound. Besides these native varieties, they also plant American staples: corn, tomatoes and varieties of lettuce and other greens.

Refugee-centered farms have significant successes: Eighty-five growers from 12 countries tended to the New Roots farm in San Diego in 2011. Farm sales at Ohio City Farm, operated by a refugee resettlement organization, totaled $177,000 in 2018. Salt City Harvest Farm in Syracuse produced over 14,000 pounds of produce for the refugees and immigrants of the city and over 1,000 pounds of produce for the Food Bank of Central New York in 2016. Just the RAPP participants in Syracuse alone harvested about 4,220 pounds of food and sold about $400 in August and $708 worth of it in the farmer’s market last year, says Colebrook.

“They [refugees] know that being outside and growing your own vegetables is healthy for you,” Colebrook says. “They’ve commented several times about how much they love being outside and being able to grow things on their own and have healthy food for their families. And they love the fact that they can provide the fresh food for their families.”

But refugee farms might be filling more gaps than just those in refugee welfare and empowerment: the number of full-time white farm operators dropped by 17 percent between 2002 and 2007, per the USDA census. As fewer Americans occupy farms, refugee and immigrant farmers — New Americans — can step in, according to Laura-Anne Minkoff-Zern, assistant professor of food studies at Syracuse University. Minkoff-Zern has studied the role of immigrant workers on farms of others for over eight years, most of whom come from agrarian backgrounds.

“People who grow our food can’t afford to get this food themselves,” she says. “But a surprising number are starting their own businesses. I say surprising because it’s difficult in the U.S. You need access to land, capital, markets and it’s very difficult to do when you have boundaries of literacy and language and inherent racial biases.”

The repercussions of this divide cannot be overstated: though refugee farmers have a wealth of knowledge, they think about it and apply it in several different languages. A dearth of translators for each language disrupts their move from the field to American markets. Literacy and language then become crucial for farming to become financially rewarding, says Jessi Lyons, a farm coordinator at Brady Faith Farm in Syracuse, one of the farms on which refugee farmers worked. Lyons teaches them how to grow for profit — she tells them if their goals are appropriate and exactly how to get there since a lot of the nuances in American groceries and markets are completely non-intuitive to New American farmers. “We can talk till we’re blue in the face about ‘don’t put out that squash, that radish is too big, nope, don’t do it,’ and they [the farmers] don’t believe us! Because that’s not intuitive,” Lyons says. “And they get out there and people are like ‘that’s a radish? No way I’m buying a radish that’s four inches long.’ And I’m like ‘told ya!’”

Lyons has helped them sell their produce at downtown and regional markets in Syracuse for the last two years and she remembers all too well the dejection they face when the rift between home country practices and American culture becomes painfully apparent. “It’s a little deflating and confusing,” she says. “They were all just very disappointed, you know, just when they walk away with a lot of produce and that was what they had for the week. But it also was valuable for helping them know what they care about because if they really want to make money, then they have to change what they’re doing.”

Despite these barriers, some refugee farmers have begun looking beyond feeding their own families and are attempting to start their own businesses. They have the agricultural know-how, they know what they want to grow and all they need now is the acreage and some logistical support, says Lyons.

Cultural idiosyncrasies like haggling and valuing quantity over quality — a trait Lyons has observed in the way farmers from African countries grow — aside, refugee farmer practices and work ethic have a high value in today’s farming environment, Lyons says, where many Americans shirk from farming because of the labor and hours involved. “Just having people share the spirit of doing this work makes the work a lot easier and enjoyable. It’s not like ‘what do you mean, I have to shovel compost for three hours?’”

Gautam echoes much the same sentiment — farming was a way of life for her and working with her hands was nothing new to Gautam, her family and her classmates.

“In my country, we also use hands because it’s easy,” she says.

Shoveling compost for three hours would be a short day for most refugee farmers, whose livelihood in their home countries depended on their small plots. Gautam’s family is no outlier: Beda Kharel and her mother, who moved to Syracuse in 2009 with a family of 15 from Nepal, spent eight hours on their farm every day. The two are among the third-year farmers alongside Gautam participating in the Syracuse RAPP.

“Back home, I take care of the cows, goats, and grow spinach, corn, maize and barley,” says Kharel, affectionately called “Beda didi” (“sister”) by the rest of her classmates. She has an 11-year-old daughter, a 5-year-old son and another 18-month old daughter. Dangly gold earrings shine from her lobes and her gentle smile is lined with bright pink lipstick, the same shade as her beanie hat. She pronounces the word “budget” as borjet. In the RISE RAPP classes, she writes in cursive, slowly and in an elegant manner, noting down plant names in one script and their English translations in another.

At Syracuse RISE classes on Saturdays, about 10 to 12 of the farmers meet to discuss a new aspect of the farming business. One weekend it would be budgets, the next it would be seasons and the next would be seeds. Classes are interactive and colorful: origami boxes of chits go around for games and it often gets boisterous with reciting and laughter. Every lesson takes twice as long, because the instructor conducts the class in English, and one of the farmers translates for the others in Nepali.

“In-come,” Kayo Green, the instructor, says and turns to Pashu, her translator.

“In-come,” he repeats and the word “income” bounces around the room before giving way to “Expense.”

“No word, no money!” warns Green, and once translated, giggles and laughs go around the room.

“I would say it’s helped improve their quality of life a lot because almost a 100 percent of farmers have agricultural experience in their home countries,” Colebrook says. “A lot of times, most of our farmers, even if they have tiny little yards because they’re renting, they’ll have buckets of plants growing on the side of their house or a little tiny piece of land that has all these plants on it. They want to farm, they want to grow things, but they just don’t have the land or resources to do it.”

Besides, providing fresh and healthy food for their families is a source of happiness and validation for many refugee farmers. Being able to grow with neighbors from the same countries is only an added bonus. At home, Gautam loves adding the seasonings she buys from the Nepali and Indian grocery stores (cumin, curry and dried mango powder among them) to her homegrown vegetables and cooking up a storm of lentil and meat curries. Her kitchen counters are overflowing with stainless-steel utensils and on the cabinets, stout spice canisters sit like sentinels, watching over the vessels.

The financial outcomes from these initiatives may swing one way or another in themselves — Colebrook says one woman saved $800 in groceries, thanks to her own farming — but the emotional rewards are no less significant, according to studies of refugee adjustment to their new homes. One 2014 study at Utah State University concluded that no farmer “named financial gain as the primary benefit from participating in the market farming program — though this was partly because the participants did not report learning large sums of money — but the effects of having space to farm seemed almost uniformly positive, for both material and emotional reasons.”

However, the warm nature of the classroom belies the challenges RISE faced in recruiting and retaining farmers for the program, which needs 20 farmers enrolled as part of the requirements. Colebrook remembers losing program managers (Green replaced a former instructor) and farm managers at Salt City Harvest Farm quitting. Moreover, the farmers themselves were initially reticent: four of them left the program because they weren’t sure what was in it for them.

“They were all like ‘why are we going to all these classes, it’s very time-consuming and we don’t have enough land to help support our families,’ so it’s hard for them to see the longer picture, the longer view of the benefits of the program,” she says. “But then moving into the second year, though, they saw that they were actually getting land, and so then they all stayed in the program because they were like ‘Wow! We do get land!’”

Bridging the gap between their agrarian knowledge and their hesitation to invest time in classes, especially when many of them have families to take care of and jobs to go to, posed an ever-present challenge. The weather turned sour? Class would get canceled. No transportation? Another obstacle to making it to class.

Manika Gautam with her son Ushan in her home in Syracuse.

Other unfortunate incidents could befall the program: Gautam fell sick the same time that she had her third child and couldn’t get out to the farm as much last year. Today, in a home crowded with bassinets, toys and formula, Gautam balances Ushan and his banana-peanut butter baby food on one arm, quiets Usha with sharp words and keeps an eye on the after-school snacks that Unisha is munching down, all in the same minute.

But patchy as it may be, the farmers’ attendance and commitment is looked upon with a more or less positive outlook. Whether they go on to start businesses or establish a flourishing backyard garden, the outcomes remain hopeful.

As April sets in and the snow begins to thaw, Gautam, Kharel, Pashu and the other farmers have begun considering the seeds they want to start and the crops they want to grow this year. They will have to wait for some time — the upstate chill won’t dissipate completely from the farms until early May. But the farmers have contingency plans already. If they can’t go to the farm, they now know enough to bring the farm to their homes.

Under dim yellow lights and surrounded by old dolls, clothes and jackets perched upon scratched suitcases — Gautam screws wires into sockets and places tiny overhead lights over the steel soil-laden beds. She flips the switch and the yellow light turned into harsh fluorescent rays that would nourish her seeds. Perfect! She smiles happily at this victory and at Usha playing with the water spray. The beds — crammed full of onions, garlic, mustard, coriander and tomato seeds — sit all over the house: three in the basement, and two in the kitchen, wherever there is enough light to soak up, real or artificial. Outside in the backyard, one 7-foot long wooden raised bed sits ready to take up the seedlings whenever they are ready to leave their little soil beds this spring.

Gautam has more good news coming this year not just from the farming, but also the U.S. government — she has just gained citizenship and is helping her first daughter, who was born in Nepal, with the process now.

“Many people telling so difficult, I am scared,” Gautam says about the process. “I apply, I got to English class, eight weeks go class. After that I am home, doing reading. It’s scary, but not difficult. I am very happy.”

She threw a party at her Northside home just a few weeks ago to celebrate her citizenship — the final step in establishing her new roots. Around nine or 10 people came along for her oath ceremony and twenty more folks put in an appearance at her party after the ceremony, enjoying the homemade rice, soup, goat meat and goat curry spread Gautam put out. Two friends — one from her RAPP class and one she met at Hopeprint, a refugee empowerment organization in Syracuse — even baked her a chocolate and vanilla cake in celebration.

By the time the party came around and as she planted her new roots in the U.S., bright green saplings had blossomed out of the soil-laden beds planted all across her home. She means to get all her necessities in order: care for the seedlings, nourish them with fertilizers and of course, adequate water.

“This year, good growth, I’m thinking,” she says with a smile.