The rise of senior food insecurity

The rise of senior food insecurity

The inside of Bruce Allen’s cabinets resembles a grocery store aisle. Cans of black beans, mixed vegetables, carrots, and evaporated milk are stacked perfectly on top of each other. But he only occasionally uses the food inside.

“Right now everything is filled,” he says. “Those are like emergencies. I haven’t touched those, I just keep them there for emergencies.”

A retired 66-year-old, Allen lives on a fixed income from Social Security. He moved to Syracuse, New York, from New Jersey in 2006 and lives alone in a two-bedroom apartment adorned with plants and photos of loved ones. He furnished the place with items from people who were moving or throwing away furniture — he bought his sectional for $20 and repurposed a headboard into a bookshelf for the living room. Allen spends most of his time in the kitchen, where everything is at his disposal: a TV, the fridge, and a window to look out into the parking lot and keep watch on the neighborhood. The chairs are adorned with “miracle cushions” he bought to try to help with lower back pain.

Allen grew up in New Jersey and worked for a sheriff’s department there for more than 20 years, but a series of injuries prevent him from working today. He is a slender man with a clean-shaven face and short dark hair, and when he walks, sometimes the bottom of his right hip will go out with no warning. The stairs leading to his apartment can be a struggle. He tried walking with a cane but it didn’t help. Allen gave his car to his son after college graduation, leaving him with few modes of transportation. For help accessing food, he turns to programs like Meals on Wheels.

He receives the meal delivery service three times a week. Each month, he gets $29 in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, $15 of which pays for Meals on Wheels. In addition to the $14 in remaining SNAP benefits, Allen sets aside about $20 of his monthly income to spend on food — typically breakfast items, bread, chocolate milk, and anything else he is craving.

“I calculate everything in my life to the penny,” Allen says.

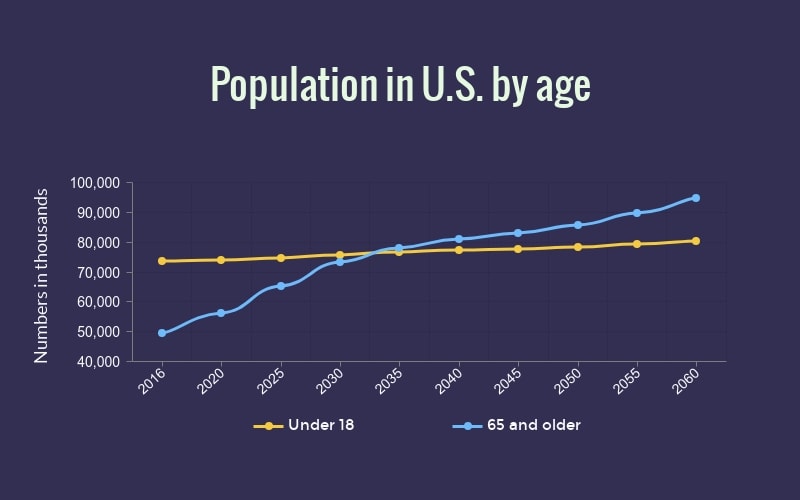

Allen is a member of the baby boomer generation. The baby boomers are aging into seniors, and by 2035, for the first time in U.S. history, the number of older adults is projected to outnumber children. Ten thousand people will turn 65 in the U.S. every day for the next 11 years.

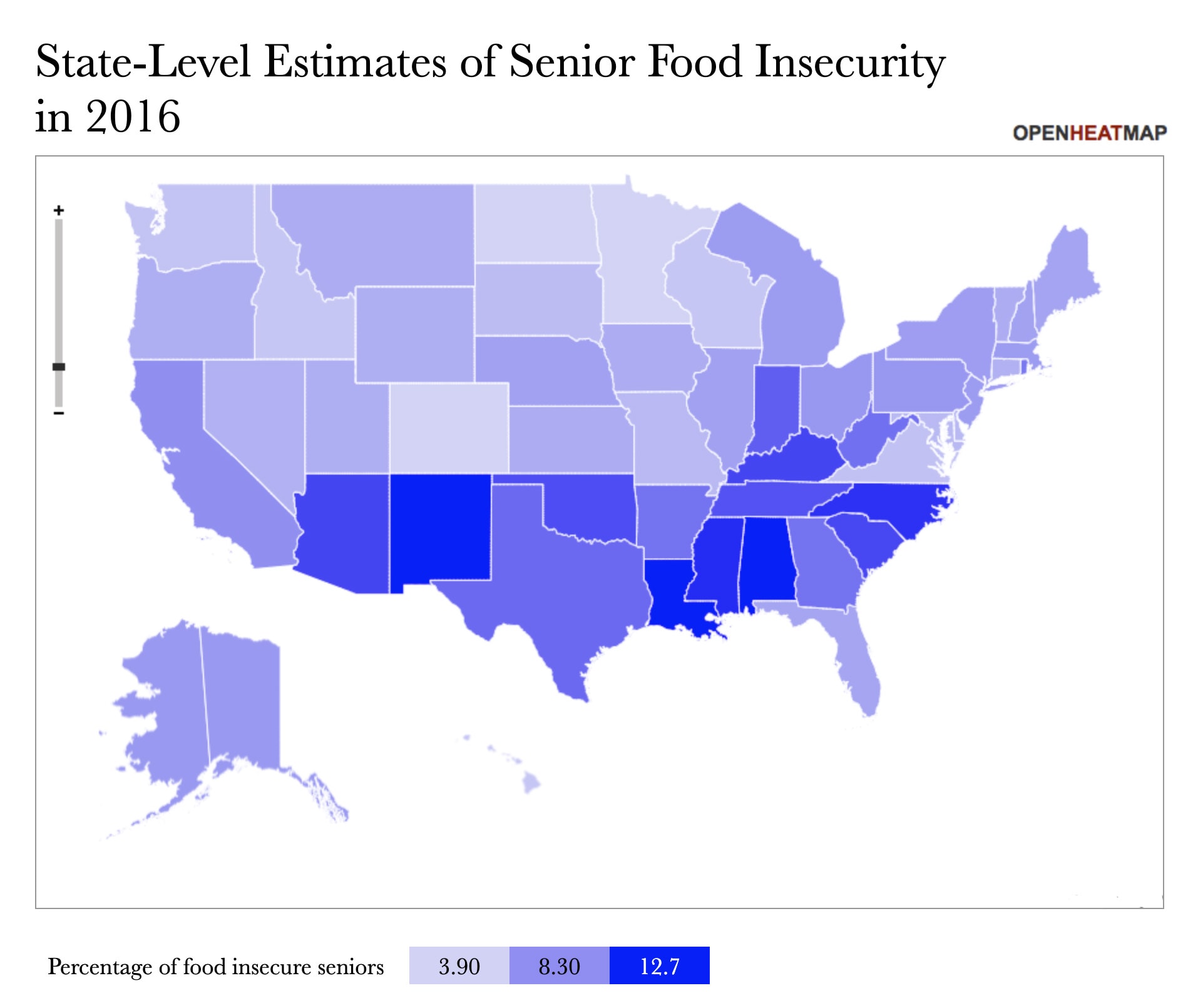

Experts predict that as the population ages, the number of seniors experiencing food insecurity will likely increase, too. Feeding America defines food insecurity as the lack of consistent access to enough food to sustain a healthy, active life. Nearly 5 million seniors were food insecure in 2016, and the organization projects that number to exceed eight million by 2050, based on population increase alone and assuming the rate of food insecurity remains the same. High rates of food insecurity among seniors are associated with poor health, which could lead to increased pressure on the already-burdened U.S. health care system.

Craig Gundersen, a professor at the University of Illinois, conducted research on senior food insecurity and notes there are health consequences associated with it. “Those are serious, we want to address them,” he says. “They can also make increases in healthcare costs.”

Local and national groups are working to help older adults gain access to enough nutritious food. Although it’s clear the problem will grow, experts are optimistic that there are solutions — but those solutions aren’t clear yet.

Food insecurity can’t be solved with just food, says Hollie Baker-Lutz, program manager for senior hunger at Feeding America. As someone who works with a network of 200 food banks on programs that serve seniors in their communities, Baker-Lutz recognizes that there are a number of underlying issues that contribute to food insecurity, including poverty, social isolation, and mobility issues.

The city of Syracuse is one of the ten poorest places in the United States. Seniors made up 15 percent of the hungry population in central and northern New York in 2017, a 10 percent increase since 2010, according to the Food Bank of Central New York. Census data shows that in 2017, 14.7 percent of the senior population in Syracuse had income below the poverty level, up from 12.5 percent in 2010. Living below the poverty level is common among Meals on Wheels clients, says Beth Gagnon, a case manager with the program who has worked with Allen. “They are often left wondering, ‘Where am I going to get my next meal?’” she says.

Some people rely on SNAP for temporary assistance as their situation changes, but that may not be the case for older adults. Many seniors have worked their whole lives and now live on a fixed income, but retirement often doesn’t look like what they thought it would — they’ve had to work longer than expected and food, rent, and medicine are more expensive. One hundred dollars in March 1980 would go as far as $317 in March 2019, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The money it takes today to make ends meet is not the same as what some folks were saving, Baker-Lutz says.

The issue of food insecurity doesn’t exist in isolation from other household needs. Sixty-three percent of senior households served by Feeding America have to choose between food and medical care. To solve the larger issue, the ways people make tradeoffs within those needs must be explored and connected, Baker-Lutz says.

But poverty rates don’t reveal the full scope of the problem. “I think the government shutdown highlighted this quite well, that there are millions of Americans who are just on the cusp of needing food assistance,” Baker-Lutz says. “These are people who we wouldn’t think of as poor or in poverty or needing help, but so many of us are one disaster away from being in that position.” It could be the car someone relies on to get to work breaks down, or a medical incident blows their savings and prevents them from working — many people don’t have a safety net.

While Allen has food stocked in his cabinets, fridge, and freezer, he worries about medical expenses. From eyeglasses to colonoscopies to dental work, medical costs add up. “Food is easy for me,” Allen says. “The medical co-pays are gonna be a little big problem.”

The impact of social isolation on seniors is another factor receiving more attention lately, Baker-Lutz says. Older adults who don’t have a support system or socialization might not have access to the food assistance they need, and there are physical, mental, and healthcare costs to that.

For some seniors, hunger is not only physical, says Julie Gilbert, resource and referral specialist at the Samaritan Center, a group meal site in Syracuse. Some people can afford to cook a hot dog at home or eat pasta every day, but it’s not beneficial for their health or their heart. They want to feel like they’re part of something, especially if they lose a spouse or their kids move away. Hunger can feel lonely, Gilbert explains. “You might be able to get Meals on Wheels at a discount or pay for people to deliver that kind of thing to your house, but what does that mean to then go and have to eat alone?” she says.

Allen says he enjoys living alone and friends are always calling and visiting. But some seniors look for ways to get out of the house.

On a Friday afternoon in Syracuse, a group of about 20 seniors gathers at the Westcott Community Center for the Senior Nutrition Program. Lunch is served each weekday at noon, and the suggested donation is $3 per person, but they don’t turn anyone away. Pizza and side salads are delivered to tables where seniors are waiting. The film Hidden Figures is playing but most people aren’t paying attention. Chatter floats throughout the room. Bingo preceded lunch and dance classes were to start after the meal.

Olga Cepeda is seated with her back to a bright yellow wall adorned with framed drawings of different neighborhoods throughout the city. The 77-year-old has been attending the program for two and a half years. Originally from the Dominican Republic, she moved to Syracuse from Sacramento, California, in 2016 to be with her siblings, and loves the cold weather. If it weren’t for the Senior Nutrition Program, it’d be harder to access healthy food, she says. “When we get this age, we get tired to cook,” Cepeda says. “It was gonna be tough if we don’t get the help.”

Carolyn E. Wallace has been attending the lunch program a couple times a week for a few years. The 69-year-old relocated to Syracuse from Alabama 50 years ago to take care of a relative’s child. If she didn’t attend the program, she says she’d cut back on her spending at the grocery store. The center also serves as a social hub and, without it, she says some of the seniors would have no place to go during the day.

The center offers free transportation to and from the program each day — a key component since lack of mobility is often another factor that contributes to social isolation and food insecurity among older adults.

While Allen finds retirement to be relaxing, his injuries occasionally impact his mobility. In 1995, he was working a temporary weekend job at BJ’s Wholesale Club and was getting ready to leave for the day when he spotted a woman trying to load a large TV on a cart. Allen tried to help her but the TV slipped and hit him in the lower back. “That really is taking its toll on my body right now,” Allen says. He kept trying to work after his injury, and pushed it until 2001 when his body just couldn’t handle it anymore. Two basketball injuries contribute to his pain, too.

Allen doesn’t go grocery shopping, TymeSavers has helped him out with that for the last two years. Every other Sunday, he gives the employee his Visa card and a list of items he needs, and she’ll pick them up from stores like Price Rite and Aldi.

He signed up for food assistance via phone, but in some states people have to visit an office to apply for benefits, Baker-Lutz notes. “If you have to get to an office and you don’t drive or have transportation, it might as well be on Mars even if it’s one county over,” she says. Long waiting lines at the offices may be a physical barrier for some older adults, too.

Even if people have access to public transportation, it comes at a price, Gilbert says. “If you decide to go to a grocery store, you live on the North Side and you want to go to Wegmans on James Street, it’s a 20-minute bus ride all the way up James Street, $2 each way. Right there before you’ve even bought a single grocery, that’s $4 out of your pocket. That’s pretty substantial.”

Meals on Wheels confronts the obstacle of mobility, but under the Trump Administration, funding for the program has been uncertain. Without government funding for meals, people might end up in nursing homes, which would cost the government more, says Karen Douglass, senior case manager. If the government were to slash funding for the program, Meals on Wheels would be in tough shape. The program couldn’t do what they’re doing without the same level of funding, she says, which has yet to rise to match the climbing prices of food.

Douglass recalls an instance when she visited the home of a client who had a disability and he asked for his weekend meals to be placed in the refrigerator. She opened the fridge to find it completely empty. “It was startling,” Douglass says. “I can still to this day, five years later, see that refrigerator that had nothing in it, and if it wasn’t for us he wouldn’t be eating.”

It’s important for seniors to have access to healthy food, as food insecurity can lead to a decline in both physical and mental health. A Feeding America study found that, compared with food secure seniors, food insecure seniors are 60 percent more likely to experience depression, and more than 50 percent likely to report a heart attack and/or develop asthma.

If seniors don’t have an adequate supply of nutritious food, then they will typically end up in the hospital, says Heather Hudson, chief programs officer of the Food Bank of CNY. They could be dehydrated or malnourished, and if they have a chronic condition, it can be exacerbated. A 2015 study in the Annals of Emergency Medicine found that more than half of older adults admitted to an emergency department were malnourished or at risk for malnutrition.

There is a negative cyclical impact to health and food insecurity that can cost society a great deal of money, Baker-Lutz says. “When people are not eating enough or not eating enough of the right food for their health, that drives healthcare costs up for everyone,” she says. “And we are certainly seeing that.” There are a lot of costly interventions, she says, but sometimes a consistent diet of enough healthy foods can make those interventions unnecessary. For those who may not be able to provide a consistent, healthy diet for themselves, programs try to step in to help.

While organizations are working to help seniors, the older population is often the most resistant population, says Amalia Swan, director of outreach and child nutrition at the Food Bank of CNY. Some seniors can be prideful — they come from a time when everybody lived nearby and helped each other, but now family is further away, and they find themselves struggling, she says. Older adults who qualify for programs including SNAP are significantly less likely to participate than other demographics — only 42 percent of eligible seniors are enrolled and receiving SNAP benefits, compared to 83 percent for all eligible people, according to the United States Department of Agriculture.

Most people looking to apply for SNAP have to pass two income tests: gross and net. But those who are over 60 or disabled only have to pass the net test. This means if they pay any medical expenses out of pocket (supplemental insurance, prescriptions), it counts as a deduction. Seniors might not know about this deduction and think they aren’t eligible, Swan says. “And if we look at what they are paying in insurances, whether it be health insurance or supplemental insurance, anything in regard to health care, they pay a high amount,” Swan says. “And that is immediately deducted off their income.”

To reach the senior population and debunk myths about food assistance, the Food Bank of CNY visits places where seniors gather — community centers, health centers, senior housing — to talk about SNAP and how to use the program. New York state is working on a SNAP application to make it easier for the older population to apply, Swan says.

Another reason seniors might avoid food assistance programs is that they feel that other people need the resources more than they do, Hudson says. They don’t want to take away from somebody else, even though with many programs, that’s not the case.

The Samaritan Center in Syracuse works to provide nutritious meals to anyone in need, seven days a week, no questions asked. Located in a former church, the towering ceilings and stained glass windows provide an elegant setting for the group meals. A cafeteria-style line resides where an altar might have been, and instead of pews, tables and chairs occupy most of the room, where roughly 100 to 200 people attend each meal. Gilbert says the center sees many seniors using its services, especially those who live alone — seniors like Otto West.

West is a shorter man with grey hair who uses a walker to get around — the result of an injury he sustained in a car accident several years back. He has been visiting the Samaritan Center one to two times a day for a couple years. “I do all my eating here mostly,” West says. He lives across the street from the program and walks over during mealtimes. But this can prove to be a challenge for the 76-year-old, he says, between his walker and the traffic. “You think this is a picnic?” he says motioning to his walker. “You take a walk with it.”

West lives alone in his one-bedroom Syracuse apartment. His two sons aren’t in the area and his ex-wife lives in a different city. He doesn’t have cooking utensils, so it’s easier to eat at the Samaritan Center, he says. He visits for the company, too. “I get to meet people, talk with them, and share experiences,” he says. “That’s why I like coming here. I sit at a table with a guy, we sit there almost all the time together.”

He walks to a convenience store near his apartment if he needs to buy any groceries — usually milk and ice cream, a treat he was known to consume religiously as a boy, even in the winter months. If he has to eat outside of the center, he’ll have a sandwich or buy a hot dog or fast food. While it’s hard for him to have food at his apartment, he says he would make do if the program didn’t exist. “I would somehow get frying pans and cooking utensils and try to do the best I could,” West says. “I’d probably end up living on microwave dinners.”

The issue of food insecurity among seniors hasn’t received as much attention as other demographics, researcher Craig Gundersen says. To rectify this, the Food and Nutrition Service, an agency of the USDA, launched a grant program to encourage researchers to look at senior food insecurity, which Gundersen is part of. As the senior population grows, he thinks there will be more of an emphasis on the topic.

“Our hope is that the research we are commissioning will lead to new insights regarding food insecurity among seniors,” Gundersen says, which could contribute to the creation of better policies to mitigate the problem. “It’s going to take some creative solutions that are different perhaps from other segments of the population.”

The antiquated way of serving people in an uncomfortable, public manner — making them line up to receive a box of food that’s been pre-selected for them and is shelf-stable, or requiring loads of paperwork and personal information — is not what people want, Baker-Lutz says.

The problem can be solved locally and nationally if people listen to what older adults are saying about what food they’d like, how they want to receive it, and what else could ease any burdens on their household, Baker-Lutz says. “If we listen to that as younger people and enact that, we can absolutely solve the problem,” she says. “I am optimistic that by doing that, we can actually solve multiple problems at once, and improve our health as a nation as well.”

Allen looks around his kitchen as sunlight streams in through the maroon curtains. Leftover pasta perches on the top shelf of the fridge, next to bread, bottles of parmesan cheese and ranch dressing, and a half gallon of chocolate milk. Sometimes, he stretches the meals he gets from Meals on Wheels by mixing them with ingredients from his “warehouse” — the food in his fridge and cupboards. “Sometimes what they have, I can’t eat it at one time, but sometimes I’m like okay, got the dirty rice, I’ll mix it with some of my beans, red beans, they got the chicken, I’ll slice up peppers and make a cacciatore, I do all of that stuff,” he says. “I’m thinking about what I want to cook today. I don’t know if I want to cook or if I want to have a Meals on Wheels dinner.

“I have the option, I always have the option.”