The Good Parts

The Good Parts

Melisa Christ remembers the world ending. It was about 20 years ago, right after her family’s move to South Korea, where her husband had been stationed as a civil engineer. For the first few months, the only people she really spent time with were her children, who kept her company as she became accustomed to an entirely new culture.

In the afternoons, her older kids would go to the local convenience store for Korean snacks as she watched the ajumma in her neighborhood — a term of respect for an older Korean woman — sweep the snow off the sidewalks with a little straw broom. Some days, when Christ arrived in her taxi with groceries, the ajumma would help her carry her bags inside in exchange for a hot drink. A great act of kindness in a time when Christ felt like a spectator in her own life, numbly carried from place to place.

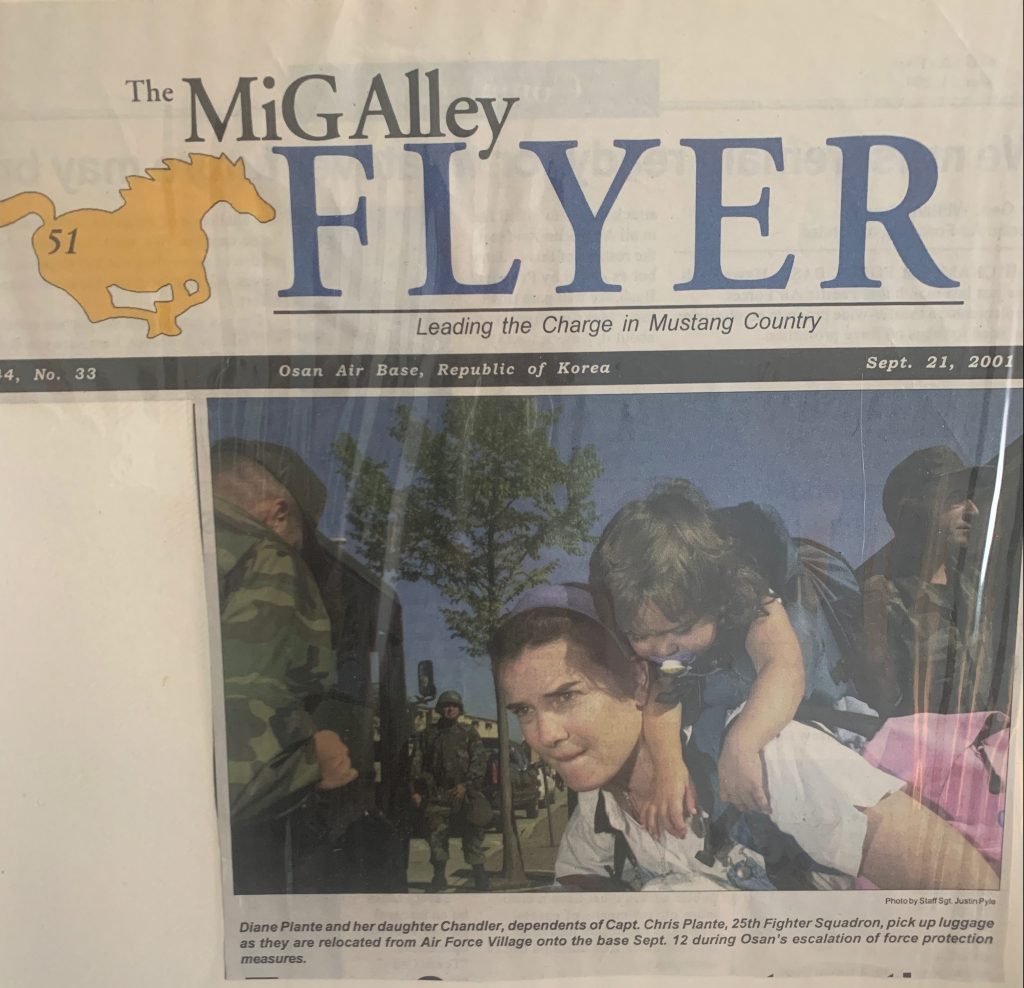

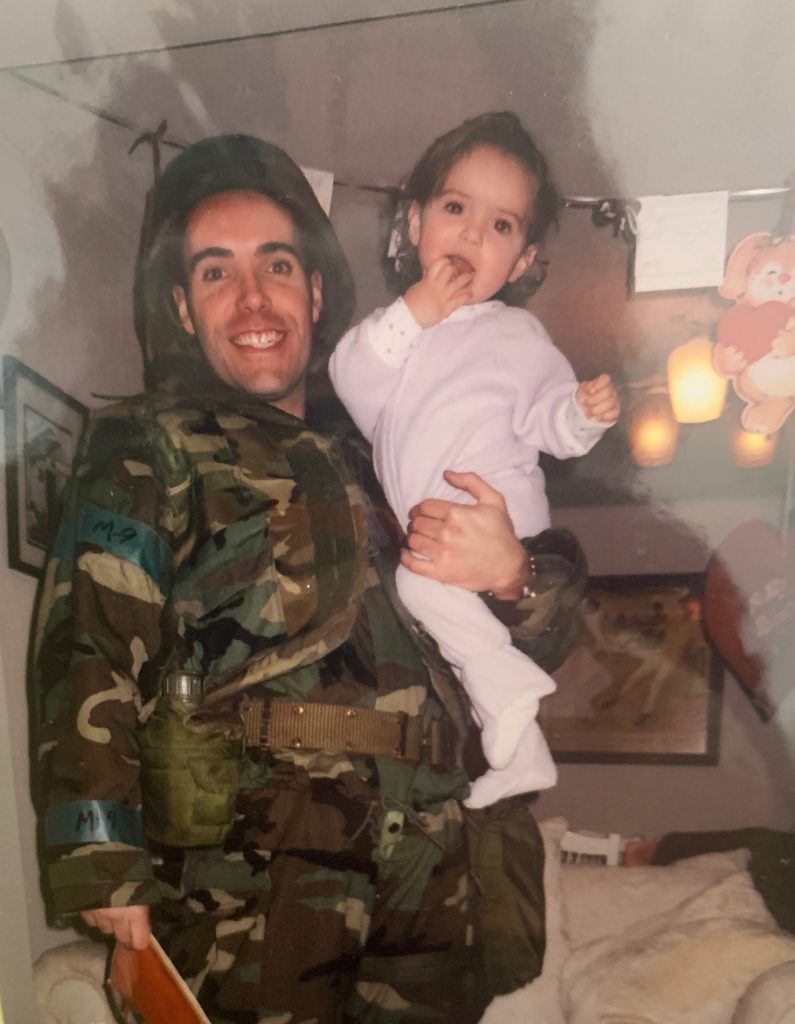

On Sept. 11 of the following year, Christ was woken by her husband to watch as two pixelated towers collapsed on their TV. A few hours later, all 50 military families living off base were packed up and taken to a high school gym far from their homes, riding through the town they had known in silence. No people roaming the street, no brooms scratching the pavement, no familiarity, no comfort.

When everyone arrived on base, their lives were separated only by the few inches of space left between the cots on the gymnasium floor. Each family was allowed one suitcase; everything else was left behind. Christ pauses in the middle of her story and I can hear her set the phone down to disguise the sound of her voice breaking. “They just showed up with busses and soldiers and machine guns,” she says. She never saw the ajumma again.

Beneath the Red, White and Blue

Most of the time, the military community makes wartime look easy. The people within it talk about families torn apart, emergency evacuations, and months of isolation as vague irritants, like running late to a meeting or watching someone chew with their mouth open. Having grown up in a military family myself, I’ve found that if you want to know the real stuff, not just stories about the unwavering joy of serving your country or the thankless honor of raising a family on your own, you’ll have to be prepared to scrape past layers of niceties and squadron barbecues. The kinds of emotional defenses that have developed over the years to make war, and military life in general, seem almost bearable.

The unpleasant reality that serving your country isn’t all that glamorous, is underlined by the sheer number of PTSD cases reported by veterans every year. Out of those who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, more than 500,000 troops have been diagnosed with PTSD, and even the statistics tying PTSD to Major Depressive Disorder with a comorbidity rate of 52% still don’t accurately depict the mental toll of war-related trauma. Then, there’s the rest of the military community to consider, with one study finding that partners of veterans with PTSD reported higher percentages of PTSD themselves. In fact, more than a third of female military spouses with at least one PTSD symptom themselves attributed their trauma either entirely or partially to their spouse’s military involvement.

Admittedly, the revelation that military life can cause trauma is not breaking news. But whether you’re going into battle yourself or supporting someone who is, the fear is non-negotiable; you either find a way to live with it, or it will find a way to break you. As Christ replays the morning after 9/11, the questions that keep tumbling out of my mouth are about how she did it, how she kept it together, how she made it past that day. Her answer is honest:

“Well, I mean, what else was there to do?”

In the years to come, when Christ saw bombs exploding on her social media feed, she’d go to bed hoping it wasn’t her spouse who had been in the wrong place at the wrong time. When her husband accompanied his friend’s remains back home, she remembered that his widowed spouse was no older than she was. And when she looks back at military life from where she is now, what she sees are these moments — the bad parts. It wasn’t until her husband retired that she finally told him she didn’t feel emotionally strong enough to go through wartime ever again.

Coping with the demands of the military is different for everyone. For Brett Waring, however, it mostly consists of creativity, distraction and a whole lot of paint. Waring is a pilot with the 47th fighter squadron in Tucson, Arizona, and an artist who paints A-10s in his free time. Even miles away, his passion for his work is obvious, and he speaks with the sincerity you would expect from a military man, talking about his work like he’s been waiting for someone to ask. Growing up, he wanted to fly planes, not paint them, but that didn’t stop him from keeping a book of aircraft nose art stashed away at the Air Force Academy.

During room inspections, one of his instructors, a former A-10 pilot himself, would grab the book and point out the jets he remembered based on the way they were painted. Inspired by these stories, Waring decided to bring his artistic talents to his own squadron, where he’s currently working on a series inspired by a WWII-era comic strip.

Waring admits that a fighter squadron might seem like a strange place for artistic expression, but he reminds me that nose art has historically been used to put young pilots at ease during wartime. “They’re worried that their lives are going to be cut short, so sometimes they translate those fears into what they produce on their airplane,” Waring says. Even if it just means sketching on a jet in grease pencil, this kind of art can be a coping mechanism.

“Death isn’t as scary when you make fun of it first,” he says.

Stacy Lanto works alongside Waring as an intelligence analyst in the same squadron, but out of the 641,639 military spouses of active duty members, she’s one of the 13% who have seen both sides of deployment.

After returning home from Afghanistan in early 2006, Lanto’s celebration was a simple one. She started the festivities by going through her apartment and flicking on every single light until the fluorescent glow threatened to engulf the entire space. After spending months in the darkness of her barracks hut, where the only brightness came from a small reading light by her bedside, she wished there were a thousand more bulbs.

Lanto peeled off her socks and heavy boots, standing barefoot for one of the first times since her deployment. Savoring the feeling of her toes sinking into the soft carpet, Lanto finally broke her silence, screaming as loudly as she could. She was glad to find that she could still produce such noise, the sound filling her up as though she had spent the past months underwater, only just now coming up for air. Her voice echoed throughout the empty rooms as she yelled, “I’m here, I’m here!” She didn’t care that no one was actually listening.

To Lanto, this moment was an indulgence. Just a few days before, her greatest luxury had been a few plastic drawers left behind by those who had lived there previously — a favor she returned by leaving a small rug and some scented body sprays for the women who would come after her. Items that wouldn’t be useful in combat, but that would help you feel a bit more yourself in a space predominantly made up of sweaty men.

But despite everything she went through overseas, Lanto swears that her role as a military spouse was much more difficult. Although being home still requires some of that survival instinct, it’s a much lonelier mission, she explains. Jessica Landgraf, another intel analyst with a military spouse, agrees that her most challenging deployment wasn’t her own. “It’s always harder being the one left at home to deal with the home life than it is to be the person who leaves,” she says.

Holding down the fort

As a former member of the National Guard, Kendra, who’s redacted her last name for privacy purposes, offers insight from a different branch of the military. When she was overseas, her demanding schedule helped to distract from the absurdity of her situation. But when Kendra’s husband was deployed, dealing with wartime became less about navigating the unknown and more about living the life she had always known under completely different circumstances.

To cope at home, every morning Kendra would accompany her kids to a jar of M&Ms, allowing her oldest to carefully extract a single piece to eat before breakfast. For her children, the crack of the candy coating was a sweet enough reward on its own, but they also knew that once each piece of chocolate was gone, it meant their dad would come home.

Christy McCoy also knows how hard it is to be the only one left with the kids when your partner is in the military. “You sometimes feel like you are failing at the stuff you know he would be better at in handling … but you can’t fail … because too many are relying on you,” she writes in an email.

Air Force spouse Jessica Gabriel can relate to this, remembering how difficult it was to help her kids through their dad’s deployment alone. “If you have kids, it is very stressful,” Gabriel says. “I didn’t really tell [my husband] any or very much of what was going on at home because he was already unhappy over there in the deployment.”

For some spouses, like Kristen, a Navy wife whose full name has also been redacted per request, the best way to keep your family sane during wartime is to keep pessimistic talk to a minimum. In fact, one of Kristen’s rules for when her spouse is away is to “speak nothing negative” to him, since he can’t do anything to make things at home better. To Kristen, the best way to deal with deployment is to keep the house running as if the spouse was there. But while preserving the usual structure can bring solace for some, being able to live unusually was what helped Marci McClain the most.

When her spouse was away, McClain vowed to avoid her normal habits as a way of lessening the pain. When her husband couldn’t make it home for her 50th birthday as she originally planned, McClain got dressed up and dug around her kitchen for peanut butter and jelly, which was the only thing she knew her husband would also have overseas. Together, the two Skyped in for a digital feast. It wasn’t the same, but creative solutions like those virtual PB&Js were what guided McClain through the stress of her spouse’s deployment.

God, Gals and Gardens

What’s consistent among a jar of M&Ms, a strict routine and a virtual birthday party is the personal comfort these strategies provide. When it comes to mental and spiritual relief, however, religion is what comes up the most. With about 70% of active-duty personnel identifying with some form of Christian faith in 2019, it makes sense that religion is a popular coping mechanism for many people within the military community, but it’s incredible just how powerful these beliefs can be.

“I would say the one thing that most helped me was my faith and trusting that we were doing what we were called to do,” says Gabriel. Similarly, throughout her husband’s 24 years of service, Susan Morrison says faith kept her fear at bay, and finding a church wherever her family ended up was always a priority. “That’s just part of our coping process,” she says. Outside of her church community, Morrison says that other military wives have also supported her, finally mentioning one of the things I’ve been eagerly waiting to talk about: the military spouse clubs.

This is where my years of training as a military brat come in handy. When I breach the topic of military spouse clubs, I’m often met with nervous giggles and reluctant half-answers. It becomes clear that no one really wants to be responsible for putting the controversy in words, but the unspoken truth is that a monthly coffee is not enough to make every single military spouse like each other.

“I always joke and say I’m probably the worst officer spouse ever,” says Shelly Hamm, a military spouse and former member of the Navy herself. Her words are carefully chosen, but she admits that it’s sometimes hard for spouses to avoid getting caught up in their partner’s job. This can lead to competition and some tension among the spouses.

Vicki, the wife of an officer in the Air Force whose last name has been redacted for privacy, confirms that the spouse clubs people are supposed to rely on are actually pretty competitive, which makes coping with wartime even harder. I ask her what’s generally required to be considered a good military spouse and she laughs, saying, “I don’t know because I never made it there!”

When the only people who can understand exactly what you’re going through don’t always have your best interest at heart, you find other support systems that will have your back. Vicki, for instance, found more refuge in her non-military friendships and Survivor marathons every Thursday night. For Lanto, it was Sex and the City and wine club with nine other trusted spouses. But for people like Christ, alone in an unfamiliar country, a lot of coping comes from learning how to be brave on your own.

Before Christ evacuated Korea, she got her Korean driver’s license so she could drive to Seoul to get flowers for what she describes as her bare, ugly yard. She and her English neighbor filled the back of Christ’s Dodge with flowers to plant, including a rainbow of soft impatiens and morning glories that snaked up the trees in rich watercolor tones. When the yard was finally complete, Korean bystanders walked back and forth between the two apartments with their hands behind their back, marveling at the crowded English gardens that had seemingly sprung up overnight.

There’s a certain tenderness in planting flowers where nothing blooms, painting cartoons on a jet known for its terrifying nose art, leaving a lamp behind in a place full of darkness — gentle reminders that humanity exists even within a community expected to act like heroes. Christ didn’t get to say goodbye to all the things that mattered to her throughout her time as a military spouse, but I have a feeling her garden is still out there. A cherished memory, a moment of strength and one of the good parts.

When a squadron gets approval to repaint their planes, their first step is choosing a theme capable of inspiring iconic designs and an appropriate amount of military humor. For Brett Waring’s squadron, the pilots landed on the Li’l Abner comic strip, with characters inspired by the fictional land of “Dogpatch, USA.” The following are the designs Waring has created and painted for the planes in his squadron, each of them a reflection of the pilot and a few beloved Dogpatchers.

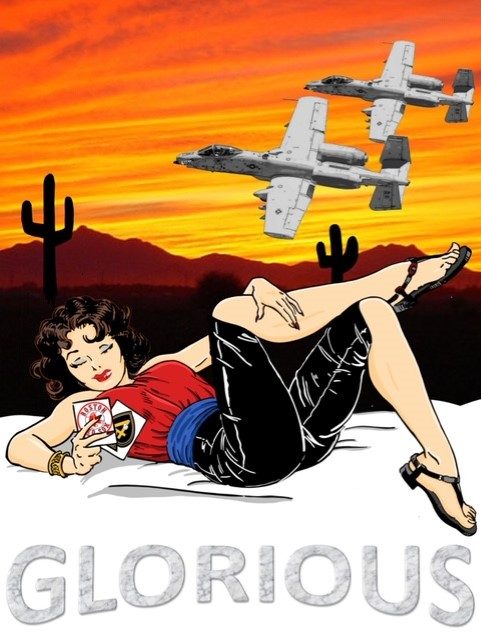

1. Glorious Gloria

This is the painting on my dad’s A-10, inspired by the Li’l Abner character “Gloria Van WelBilt” (say what you want, but my father is a man of class). Although the original comic shows her sifting through pictures of potential suitors, Waring changed these into cards representative of my dad’s favorite things: his squadron and the Boston Red Sox.

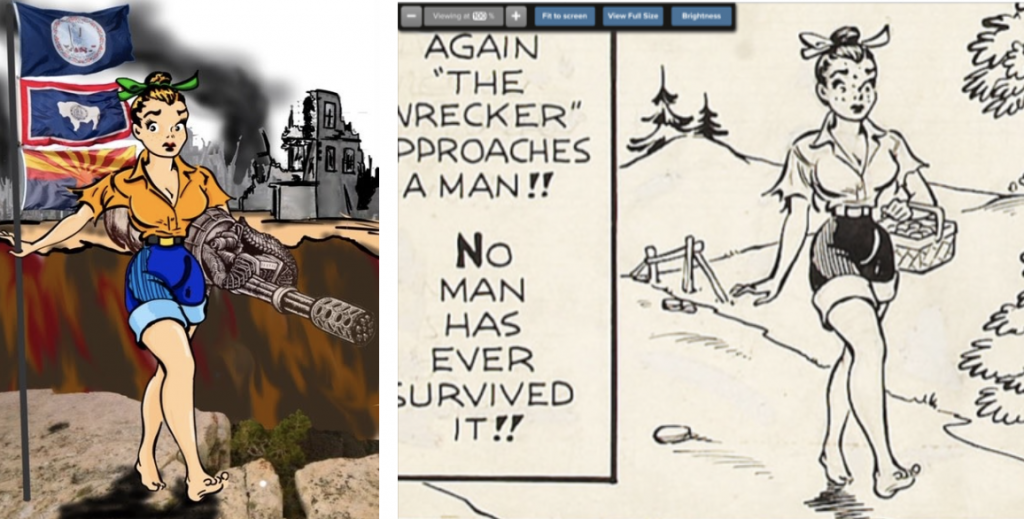

2. The Wrecker

This piece was a commission from one of Waring’s fellow pilots, featuring the actual Li’l Abner comic that inspired the final design. When creating the characters originally drawn by Al Capp, Waring digitally traces the artwork in an effort to retain the original look and history behind each sketch. In this case, the end result was a modernized version of the WWII-era cartoon, except with a miniature A-10 gun instead of a basket. Hey, times change.

3. Moonbeam McSwine

One of the more popular characters from the comic strip, Moonbeam McSwine was hand-painted onto this jet for its long-time pilot. To get the dimensions right, Waring projected his reference image onto the door, but did the rest of the details himself. The following show the progression of the artwork as it was painted onto the plane.

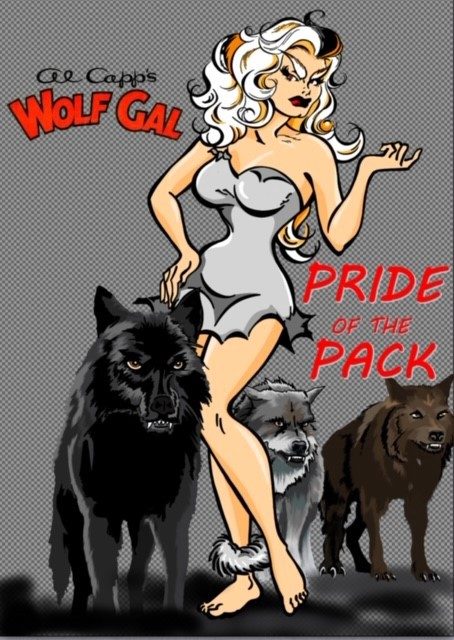

4. Wolf Gal

Waring’s own jet required him to merge two images from the comic. The wolves, on the other hand, were inspired by a Twilight movie poster. As Waring says, “I didn’t like those movies (vampires don’t glisten in the sun — they burn up!!!) but the wolves looked cool enough to get put on an A-10.”