Mother-daughter team goes for knockout in fight with Parkinson’s disease

Mother-daughter team goes for knockout in fight with Parkinson's

A heavy bag hangs from the ceiling of the brightly lit rehab center as twenty-four boxers snake between exercise machines rotating between stations in the makeshift boxing gym. ┬ĀKaren Cretaro, a 64-year-old grandmother with muscles rippling under a black tank top, circles the heavy bag and throws a series of crosses and jabs. Her short, dirty-blonde hair clings to the sweat on her forehead, and her bright, salmon-colored shoes shuffle in purposeful movements. With each punch, she hits words scribbled onto the bagŌĆÖs white canvas: ┬Āmuscle pain, no smile, slower than slow.

ŌĆ£I look at the words and I think, ŌĆśWho wrote that down?ŌĆÖŌĆØ Cretaro said. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs all the same things that we all hate about living with ParkinsonŌĆÖs.ŌĆØ

The heavy bag invites boxers to vent their frustrations and literally pummel the symptoms that make living with the neurodegenerative disorder difficult. Parkinson’s disease has no cure, but medications, exercise, and sometimes surgery help manage symptoms. Patients lose motor functions as the disease slowly maroons the body, isolating it from the functions of the mind. The neurological disorder affects one in 100 people over age 60, and there are nearly 1 million people living with ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease in the United States, according to The Michael J. Fox Foundation.

ŌĆ£ParkinsonŌĆÖs is the fastest growing neurological disorder in older adults,ŌĆØ said Dr. Jeff Bauer, a researcher currently studying ParkinsonŌĆÖs and a professor at SUNY-Cortland. ┬ĀŌĆ£We are passing Alzheimer’s, and several others because of its increased awareness.ŌĆØ

But four days a week, this soon-to-be-closing outpatient clinic treats no patients ŌĆö only trains boxers. It houses SyracuseŌĆÖs affiliate of Rock Steady Boxing. There are more than 500 Rock Steady Boxing affiliates around the world. The program began in 2006 in Indiana with only a few boxers and experienced exponential growth after it was featured on 60 Minutes in 2015. The non-contact boxing therapy targets the loss of motor skill functions associated with the disease.

"I understand it differently, because I live with it every day. So, I can see when people are struggling, and know exactly what they mean when they tell me about it." - Karen Cretaro

Ed Regan, a 69-year-old construction manager, said he loves the programŌĆÖs camaraderie and familial bond.

The local chapter celebrated its one year anniversary in February, and boasts 25 boxers who attend classes. But its current location at the Centers at St. Camillus outpatient clinic is closing as the facility downsizes. Coaches Patrick VanBeveren, Julie Lombardi and Karen Cretaro are working to make sure the program can continue in a new space. They are in current talks with potential host sites, but havenŌĆÖt secured a new location.

ŌĆ£We don’t want to lose this family that we have put together,ŌĆØ said Lombardi, a physical therapist who has worked extensively with ParkinsonŌĆÖs patients the last 20 years.

For Lombardi, those relationships represent more than the close-knit atmosphere of the clinic.Her mother, Cretaro, the boxer in salmon-colored kicks, is both coach and ParkinsonŌĆÖs patient. On this day, Cretaro finishes her station by walloping the punching bag on a single phrase, a single symptom that started her battle: CanŌĆÖt Write.

In the family

In September 2015, after hanging up a phone call at her family-owned auto body shop in North Syracuse, Cretaro checked the notes she just scribbled. The handwriting was cramped, all the letters bent into one another ŌĆö illegible. Over the course of that year before her diagnosis, more symptoms began to appear. Physical challenges that were familiar from conversations with both her physical therapist daughter and from her husband, whose father suffered from ParkinsonŌĆÖs. She began to try to hide these symptoms from her family, friends and customers for almost a year.

ŌĆ£I was always looking for signs in my husband, cramped handwriting being one of them,ŌĆØ Cretaro said. ŌĆ£I remember thinking, ŌĆśAm I so worried about my husband getting ParkinsonŌĆÖs, that IŌĆÖm talking myself into it?ŌĆØ

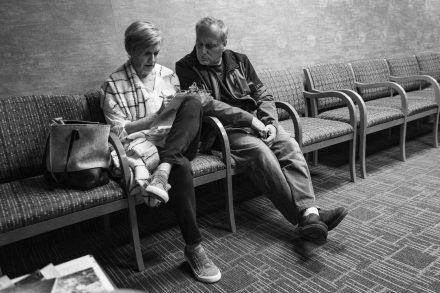

She went to specialists for her hoarse throat, made appointments to talk about her gait imbalance. Sitting in bed, she would convince herself that today would be the day that everything would be normal. She would will her arms to swing freely when she walked, she wouldnŌĆÖt feel like she was staggering drunk when walking in a straight line, and her body wouldnŌĆÖt feel so tired.

But ParkinsonŌĆÖs can be difficult to diagnose. ŌĆ£Parkinson’s is diagnosed by ruling out everything else: brain tumors, cancer, ŌĆØ said Bauer. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs unique to each patient. ItŌĆÖs nice to have a recipe, and ParkinsonŌĆÖs doesnŌĆÖt let you do that.ŌĆØ

Everyday, CretaroŌĆÖs symptoms became her new normal. She would find herself hunched over her kitchen counter, her left hand contorted as if she was about to cut an apple, and not know how or why she got there. As her symptoms worsened, she searched for answers. ŌĆ£I would find articles online that would say, ŌĆś10 common symptoms of Parkinson’s,ŌĆÖ and I remember going through one checklist and it said if you have experienced four or five of these symptoms you should see a neurologist,ŌĆØ Cretaro said. ŌĆ£I had checked seven of them.ŌĆØ

Finally, in the fall 2016, she decided to see a neurologist. But first she told her daughter, who struggled to understand how, after years of working with ParkinsonŌĆÖs patients, she missed the disease she knew so well in her own mother.

But soon after, she realized why her patients often take years to go to the doctors: a mix of fear, and a variety of different symptoms that can happen over a long period of time. ŌĆ£I think when you have a loved one who has a diagnosis like this you feel hopeless and you want to do something to help,ŌĆØ Lombardi said. ŌĆ£With this I have physical ways to help.ŌĆØ

Lombardi, 39, has been helping people with Parkinson’s since her time at Upstate Medical University. She doesnŌĆÖt know why, but she always felt drawn to people with the disease. Then her mother was diagnosed, and that connection deepened.

For Cretaro, ParkinsonŌĆÖs became another reason to question and understand why bad things happen to people ŌĆö people like her. When she was 14, her mother died. When she was in her 50s, she successfully battled breast cancer. And now in her early 60s, sheŌĆÖs working to combat ParkinsonŌĆÖs. ŌĆ£When something bad happens to you, you think, ŌĆśWhy? Why me?ŌĆÖ Maybe this is the reason.ŌĆØ Cretaro said. ŌĆ£Julie and I can make a difference in this community, or at least we are going try.ŌĆØ

In this corner: hope

On a January night, Cretaro coached the class. She walks over to a tall man frozen in front of a heavy bag. The boxer furrows his brow, and adjusts his white hair under his athletic headband. She offers soft words of encouragement, ŌĆ£You can do it.ŌĆØ

Ed ReganŌĆÖs hands barely smack the bag.

ŌĆ£What is that? You can do better than that,ŌĆØ Cretaro said, her voice raising to a goading shout.

In his head, he tells his gloved hands to smash against the bagŌĆÖs plush exterior. But they wonŌĆÖt. Then, between CretaroŌĆÖs encouragement and imploring, ReganŌĆÖs hands come alive, and he throws a series of hooks until the rest buzzer sounds. A smile creeps across his face, and his tall frame engulfs Cretaro in a hug.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs nice to have Karen as a coach, someone who knows what youŌĆÖre going through, someone who gets it,ŌĆØ said Regan, a 69-year-old construction manager. ŌĆØWhen you get diagnosed with something like this you can feel pretty lonely, but here thereŌĆÖs a real sense of camaraderie.ŌĆØ

As the boxers stretch to cool down, they talk about their symptoms, and how theyŌĆÖre feeling that day, but often the conversations quickly turn away from the reason they gather in this room. They talk about the music playing on the bluetooth speakers, check in about one anotherŌĆÖs kids, and often crack lewd jokes that send the room into fits of laughter.

ŌĆ£They come here, they find people that are experiencing the exact same thing,ŌĆØ said Patrick VanBeveren, Rock Steady Boxing coach. ŌĆ£Today, everyone was laughing. You have ParkinsonŌĆÖs, and you’re sitting at home alone, you donŌĆÖt laugh, itŌĆÖs not funny. They come here that changes.ŌĆØ

The coaches hope that Syracuse Rock Steady Boxing will continue to expand, and find a new home.

VanBeveren also hopes to bring the price point down, currently at $75 for a month of classes that meet twice a week, and make it more affordable for people to get the help they need. He wants to hold fundraisers where people sponsor boxers to bolster the program. Lombardi wants to help boxers enroll in research studies that could both benefit them and the larger ParkinsonŌĆÖs community.

ŌĆ£People come here lost and afraid. But when they walk through these doors, they have hope,ŌĆØ Cretaro said, wiping tears from the corners of her eyes. ŌĆ£I have hope.ŌĆØ

At the end of this Monday night practice, Cretaro is the last boxer to leave. She shuts off the lights and walks past a framed poster with a similar message: ŌĆ£In this corner ŌĆ” HOPE.ŌĆØ