Keeping the peace

Keeping the peace

With one swift blow on the cobalt blue harmonica she wears around her neck, Suzanne Phillips, a first-grade teacher at Dr. King Elementary School in Syracuse, can turn a chaotic room of screaming kids into a silent room of scholars.

A rainbow of multicolored posters covers the walls of room A-236. Phrases like “Welcome to Noun Town” and “Keep on Reading” grace the posters in bold letters. Words of encouragement and positive affirmation surround the primarily African-American class of 20. Phillips, a tall, brunette Caucasian woman has worked in the Syracuse City School District for 17 years, exercises gentle-but-firm control over her class.

“Look at all these PAX leaders!” Phillips said as she walks her class to the lunchroom. First-grader-sized fingers spring into the air, forming peace signs, as the students descend to the cafeteria

The peace signs, the harmonica, and the term “PAX leader” all act as integral elements of a behavioral practice that the school and the district implemented this year. The PAX Good Behavior Game is a 50-year-old restorative behavioral practice that many districts around the United States and Canada use, often times, to combat high suspension rates.

PAX, which means “peace” in Latin, is designed to encourage students to self-regulate. Created in part by Dennis Embry, a developmental psychologist and president of the PAXIS Institute in Tucson, Arizona. As part of the PAX Good Behavior Game, a form of preventative science, teachers positively reinforce the absence of bad behaviors rather than praise students for good behaviors.

“Those are two separate mechanisms in the brain,” Embry explained. “Most people don’t understand that.”

Restorative practices often involve mediations or open dialogues that help foster closer relationships between teachers and students. These practices integrate mental health awareness into discipline management and teacher-student relationships. Strengthening these relationships inherently decreases student misbehaviors, said Ondine Gross, a school psychologist and author of “Restore the Respect: How to Mediate School Conflicts and Keep Students Learning.”

Some iterations of these practices operate through a trauma-informed lens, such as in the case of PAX. Through this lens, teachers must take a child’s traumatic experiences into account when practicing discipline. If a child’s basic needs such as adequate food and rest are not met, they are not ready to learn, said Tiffany Williams, a first-grade teacher at Dr. King. Practices like PAX aim to dissipate the wall that often forms between teachers and students — a wall of ignorance, misunderstanding, and biases from both sides.

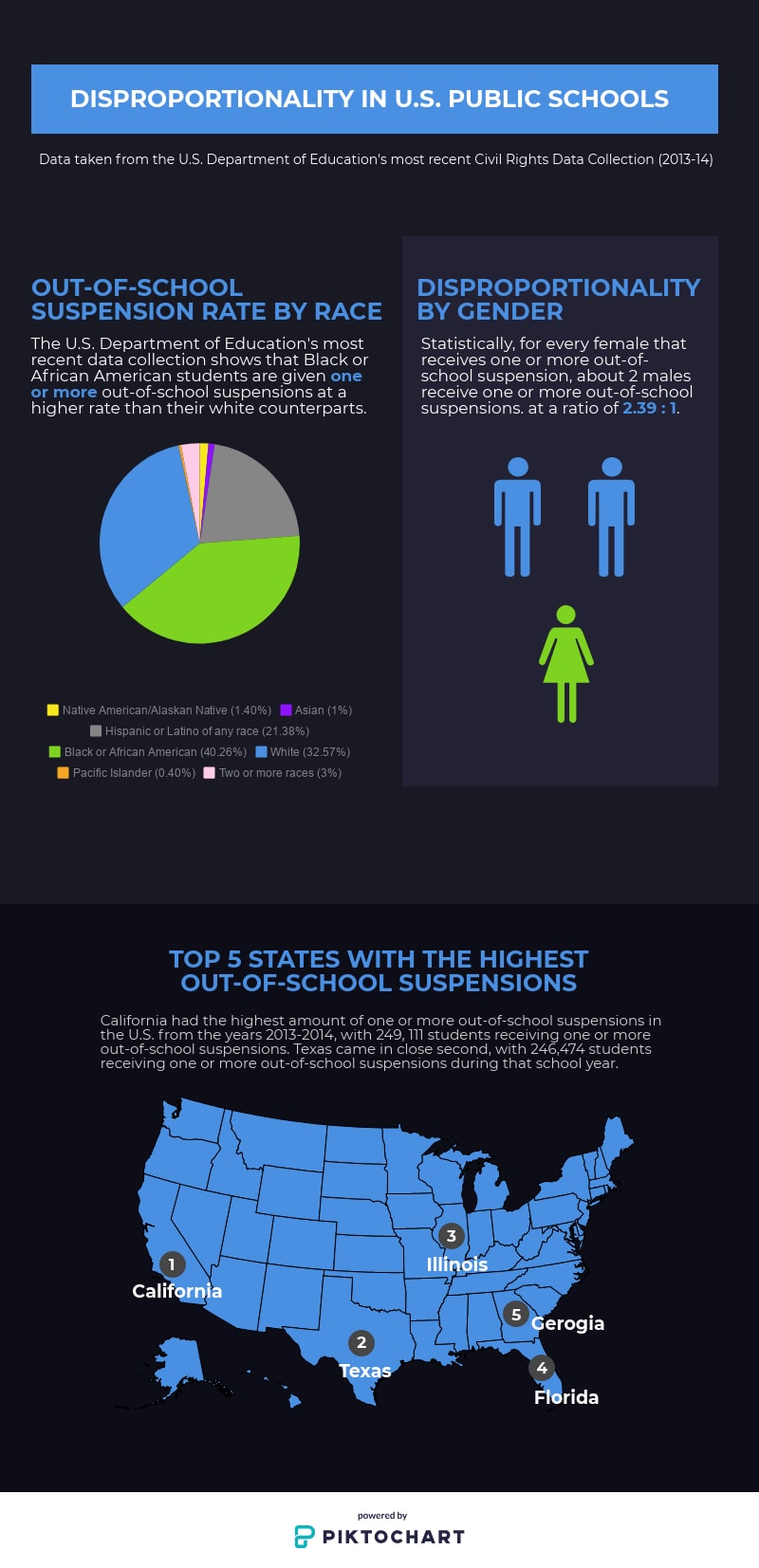

Recent suspension rates trending downward

About 2,635,743 public school students received one or more out-of-school suspensions during the 2013-2014 school year, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s most recent data analysis. This figure showed a 17 percent decrease from the previous school year, depicting a downward trend in suspension rates. This trend is reflected in Syracuse’s school district. The district’s suspension rate dropped from 45 percent during the 2013-2014 school year to 11 percent during 2015-2016. Rates continue to trend downward this year due to the district’s implementation of the PAX Good Behavior Game, according to Julia Yeatts, a Syracuse University Literacy Corps supervisor in the district.

But it would be unrealistic to claim that improved student behavior is the sole cause of the statistical plummet, Suzanne Phillips said. It could be the school’s resistance to give out suspensions.

“I think (the administration) is afraid to suspend because of the recent backlash that we’ve gotten for high suspension rates,” Phillips said. This is a problem because some students who should be suspended are not, she said.

Sometimes suspension is necessary for students who threaten the safety of their peers and teachers, Phillips added. However, it varies case-by-case. One of Phillips’ current students accumulated the majority of her 19 office discipline referrals this year, a number she has never reached this early in the school year. From a social-emotional standpoint, he needs resources beyond what the school can provide, Phillips said. In this case, a suspension would be counter-intuitive.

Because of students like him, some psychologists and researchers view suspension in a negative light, as removing kids from the classroom hinders their educational and social growth. In many schools, the same 10 to 15 percent of kids repeatedly misbehave, according to Ondine Gross. This fosters self-fulfilling prophecies. Students expect to be punished. Teachers become the enemy and students shut down on them, Gross said. An important component of this often negative teacher-student dynamic is an implicit bias that creates systemic disproportionality where, according to national data, black students are punished and suspended more than white students.

Disproportionality and implicit bias

Black or African-American students receive one or more out-of-school suspensions — about 7 percent more times than white students, according to U.S. Department of Education data from the 2013-2014 school year.

This disparity among black and white student suspensions increased by 3 percent from two years prior. Implicit bias plays a major role in this ongoing systemic problem, said Joe Horan, creator of a young men’s mentorship program in Syracuse known as Building Men.

“We have young men of color (who go) through their whole career being taught by white women,” Horan argued. This is where implicit bias can skew the teacher’s ability to properly discipline. Alternatively, the student’s implicit bias can foster an attitude of disrespect toward their white teacher, to whom they cannot relate.

Some argue that disproportionality is best analyzed on a school-by-school basis, as many urban schools teach to a primarily black student body.

“You can’t make that statement and say that we’re suspending African Americans at a disproportionate rate when we are mainly teaching to African Americans,” Phillips said.

While her statement holds valid reasoning, it suggests a deeper systemic problem that the schools giving out high numbers of suspensions are those that teach primarily to students of color. But teachers also hold implicit biases that can heavily influence their interactions with students. At a Syracuse University Literacy Corps event, professor of religion Biko Mandela Gray argued that classrooms are structured based on behavioral and learning standards of white people. Students are expected to operate and learn in silence, he said.

But some students learn best by talking and socializing with others—by making noise. Forcing kids into a mold that does not fit their learning style or a behavioral standard that isn’t consistent with that of their standards at home is going to incite misbehavior, Gray said.

“Specifically for black folks, our standard of learning is noise,” Gray explained. “The problem is not what is happening outside of the classroom. The problem is how the teachers are normatively structuring their classrooms.”

Restorative practices and relationship-building

Although disproportionality is still evident in the United States education system, many schools are aware of it and are actively trying to fix it through restorative practices. Texas principal Christopher Eckford explained that in many Texas schools, homeroom has been replaced with a restorative period. Students circle up and talk about whatever is on their mind, at their own discretion. Creating this safe space for students to express themselves allows teachers to become aware of their students’ personal struggles. This information is then passed down to administrators, so that if a kid is acting out, certain disciplinary actions may be scaled back to accommodate the child’s personal needs, Eckford explained. All of this comes down to a simple yet highly important component of teaching: building relationships with students.

“We cry on each other’s shoulders. [My students] mess up my shirts and my suits,” Eckford said. “Kids don’t work for people they don’t like.”

Things like remembering their birthdays or going to their soccer games help form relationships that can completely change students’ attitudes and motivation in school, Eckford argues. Many students are not intrinsically motivated to work diligently in school, so teacher-student relationships can provide an incentive for them.

Whether a school utilizes a structured behavioral management program, such as PAX, or simply fosters positive teacher-student relationships, restorative practices are present all over the nation. Teachers and administrators know that traditional punitive behavioral methods are not always effective, but implementing restorative practices with fidelity is not an easy task. There is only so much that can be done in school. Often times, there are pieces outside of school that must be resolved.

“There’s a small percentage (of parents) that just throw everything on to the city schools and want us to fix everything when we’re just one part. They need to fulfill their part,” Suzanne Phillips said. “Because they’re not willing to play their part, we’re stuck with a scholar that comes back in the classroom with no social or emotional needs met.”