Animal hospitals are understaffed amid a local high pet population

Understaffed animal hospitals struggle to aid local pet population

Previous SPCA Humane Education Director Dee Schaefer spent her Monday in July answering calls at the front desk due to a staff shortage. A pitbull roamed the lobby and a white cat lain on the chair next to the reception desk while she worked.

At the SPCA, there is one vet who is on call 24/7 responsible for 200 animals, Schaefer said.

The workload is just as intense at the Liverpool Village Animal Hospital as they are receiving 1,000 calls a day, the hospital’s owner said. Vets at the Fayetteville Veterinary Hospital are working more than a usual 40-hour work week, one vet said.

Syracuse Veterinary offices have been struggling for some time to find staff. Dr. Douglas Wojcik, one of the vets at Liverpool Village Animal Hospital, explains that a lack of veterinary professionals combined with a growing number of clients caused a backup of appointments.

The problem is now self-perpetuating. Without sufficient vet services, there are fewer neutering and spaying surgeries. This means more puppies and kittens, and it all leads to more burnout among the staff, Schaefer said. It’s all happening as fewer people are graduating from veterinary school, Wojcik and others said.

“It is a huge issue right now. What a lot of people don’t realize is animal welfare is in crisis right now,” Schaefer said. “There’s not enough vets, there’s not enough shelter workers, there’s not enough fosters.”

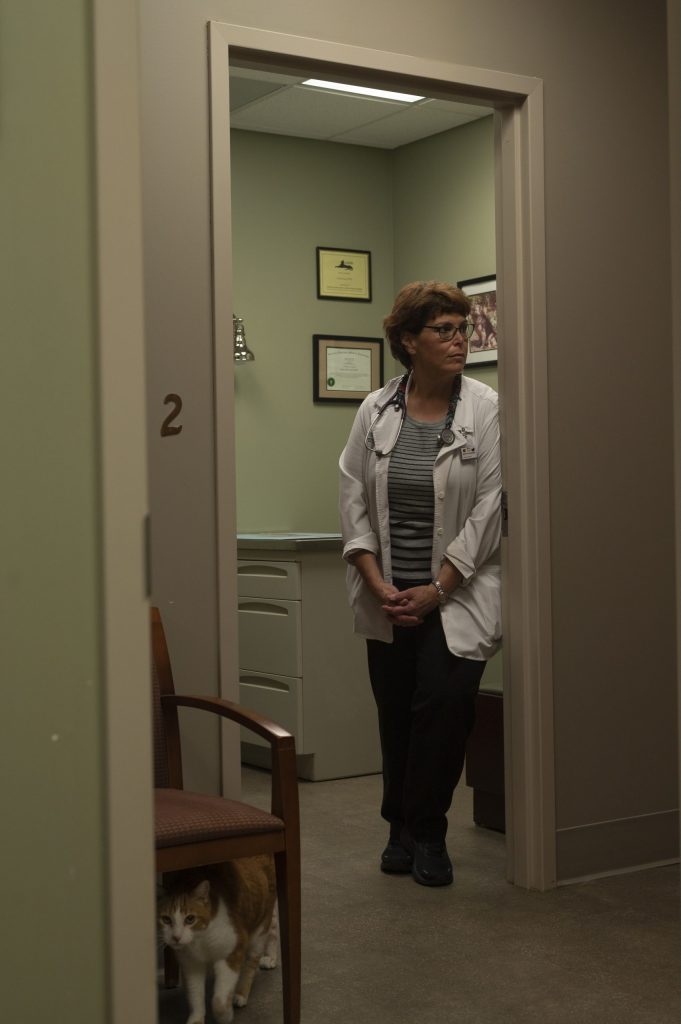

Ziegler-Alexander does a routine body examination on a cat.

Ziegler-Alexander looks outside of the examination room at another vet.

Right now, there are only 146 veterinarians who live in Onondaga County treating an estimated 200,000 cats and dogs. While no one has a complete count on the number of dogs and cats, one estimate puts the number at around 200,000, based on Census data and calculations by the American Vet Medical Association.

Meanwhile, there are 7,163 veterinarians licensed in the entire state treating an estimated 6.5 million cats and dogs, according to the NYS Boards for Medicine and Veterinary Medicine and the American Vet Medical Association’s analyses.

Liverpool Village Animal Hospital is one clinic in the area that is having trouble finding new vets. For three months, the hospital received no response for the two vet applications, Wojcik said. While the hospital is still in the process of interviews, Wojcik reports that there have been few replies overall.

As one of the largest practices in the area, Liverpool staffs 13 vets who are able to take clients quicker than other vets in the area. However, the wait time is still over a month for nonurgent patients. Pets and owners are often forced to wait for an appointment since the hospital can only squeeze in urgent patients, Wojcik said.

The hospital isn’t turning away urgent patients, Wojcik said, but accommodating every case is not easy.

“We’re all trying very hard, but be patient with us, please,” Wojcik said.

At the SPCA there’s an adopted sign hanging on the crate of a white and gray dog named Matt. The seven-year-old arrived on July 25 and is already set to be adopted, along with two-month-old brown tiger kitten Parsley. Yet Parsley’s orange companion and roommate, another two-month-old kitten Peppermint, has not been adopted.

While there has consistently been a shortage of vets, the problem increased due to the pandemic, when there was a surge in pet adoptions. The Central New York Cat Coalition tallied a record high of 1,000 adoptions in cats alone in 2020, almost 200 more adoptions than in previous years.

With increased adoptions and the pandemic, new and existing patients couldn’t get an appointment during the coronavirus restrictions in New York, Schaefer said, which has only compounded the backlog.

Vets are overworked with the volume of animals coming in. More animals to treat lead to more hours and potential for vet burnout, Wojcik said. One vet is seeing at almost 20 animals a day, a significantly high volume of patients, according to Wojcik.

Even places that don’t have trouble finding new vets are still working outside of their 40 hours a week. At the Fayetteville Veterinary Hospital, one of the veterinarians explains that four vets are working 50 hours a week, and sometimes on their days off, to respond to client follow-ups and calls, Dr. Mike Bunnell said.

COVID-19 has also affected the mental health of the veterinary staff. Especially since the pandemic started, veterinarians and vet technicians have experienced burnout, Schaefer said.

This is more often known in the medical field as compassion fatigue, Wojcik said.

Burnout or compassion fatigue can come from stress or being overworked. A vet tech at the SPCA left the field during the pandemic due to burnout, Schaefer said.

“It’s an unsustainable level of stress at the current level we are dealing with,” Wojcik said.

Vets have an increased suicide risk, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Women veterinarians are 3.5 times more likely to die by suicide and men are 2.1 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population, the CDC said.

However, the shortage of vets isn’t only because of the pandemic and burnout. This also has to do with the number of veterinarians that are graduating from college, Wojcik said.

Only 1,432 people in New York have entered the veterinary profession in the last 10 years, according to the New York State Boards for Medicine and Veterinary Medicine. In 2021, only 432 people received veterinary licenses in New York State, according to the NYSBoards for Medicine and Veterinary Medicine.

Rachel Qiao graduated from Cornell in 2021 and is on track to becoming a veterinarian. The rigorous classes, extensive schooling and cost of tuition often deters students from becoming veterinarians, Qiao said.

Many students have to take out loans, Qiao said. The average debt for veterinary students in 2020 was estimated to be $157,146, according to AVMA.

The cost of tuition is steep, but graduates are almost guaranteed to get a job after school, Wojcik and other vets said.

While veterinarians and staff in the field are aware of the shortage, there isn’t an easy fix, Schaefer said.

“I wish I knew what the answer was,” Schaefer said. “I wish I knew how to make it better. But I don’t.”

Within the past month after speaking with Schaefer, she resigned as the SPCA Humane Education Director.

She is no longer at the shelter due to stress, Schaefer said.