The American Dream hides somewhere along the U.S.-Mexico border

The American Dream hides somewhere along the U.S.-Mexico border

Before the COVID-19 pandemic and the gruesome murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police showed us the true depths to which this country could sink, America seemed to be a nation reaching the peak of its division. The DNC-led House of Representatives voted to impeach the president before ultimately seeing the motion quashed by the GOP-led Senate. The Democratic Party faced an identity crisis as its members toyed with the idea of moving further left under the lead of Bernie Sanders before ultimately choosing the establishment favorite in Joe Biden. And all the while, the stock market set record highs whilst the gap between the rich and poor reached its highest level in over 50 years.

In the midst of these events, millions of immigrants journeyed to the U.S.-Mexico border in search of newfound freedom, only to find themselves arrested upon entry or, should they be fortunate enough to make it through, subjected to violence at the hands of disempowered White bigots seeking power in a country they felt had left them behind. Despite being a nation built off the promises of freedom and opportunity, America seemed to be a place that had lost its Dream.

In January, I decided to set out to the border itself, the place where those still seeking The American Dream first land their feet, to explore whatever semblance of The American Dream might be left. While today’s problems and injustices leave little optimism and room for such abstract adventures, I invite you on this adventure so that you may see and decide for yourself what version of The American Dream still exists. With migrants being one of the populations most vulnerable to both systemic racism the inequalities brought on by COVID-19, those seeking newfound freedom in our country remain a group as important as any as we move forward in rebuilding an American society that belongs to all people. — A.J.R.

In January, I decided to set out to the border itself, the place where those still seeking The American Dream first land their feet, to explore whatever semblance of The American Dream might be left. While today’s problems and injustices leave little optimism and room for such abstract adventures, I invite you on this adventure so that you may see and decide for yourself what version of The American Dream still exists. With migrants being one of the populations most vulnerable to both systemic racism the inequalities brought on by COVID-19, those seeking newfound freedom in our country remain a group as important as any as we move forward in rebuilding an American society that belongs to all people. — A.J.R.

The afternoon sun hung low over the lonely gravel paths and lush, green shrubs that dotted Border Field State Park in the Tijuana River Valley near the most western part of the California-Mexico border. A thousand feet of murky, green water stood between me and The Wall — the projected 2,000-mile row of steel spikes that serves as a political dog whistle, a metaphor for American muscle, and a tempestuous siren for those escaping misery and violence. I saw only two ways around the green cesspool — a gravel path on the left and a gravel path on the right. I chose left. It hadn’t rained in San Diego in more than seven days, but the standing water looked like it’d been rotting for weeks. About 300 feet into the path, it became clear I chose the wrong way as the mud gave way to green water. But hell, I thought, someone who needed to cross the border wouldn’t stop for a little water. Why should I?

Wobbling on one leg, I removed my white, now brown, Stan Smiths and sunk my bare feet into the mushy gunk below. The trench became deeper, and the water hit my calves. Step after step, spiky swamp plants jabbed at my soles. The water stank like a septic tank, and the number of sewer gnats swarming the area justified my concerns over the questionable ecology swimming below. After 20 minutes of wading, I transitioned from water to olive-colored mud, hoping to find my feet free of open wounds. And after walking about a hundred more feet through sticky clay, I made it to The Wall. I reached inside my bag for my camera, and two white Chevy border trucks rushed in from both sides.

One van hung back; the other pulled up next to me. A white-haired border agent with arms like a middle-aged Schwarzenegger and the demeanor of Stephen Lang’s Avatar character stared me down.

“What’re you up to here?” he asked. “You know you can’t get too close to the fence. It’s federal land.” Doing my best innocent traveler impression, I said something like, “I just wanted to get close to take some pictures. I’m a journalist searching for The American Dream.” That seemed to satisfy him, and he started to pull away.

“I just walked through that horrible swamp back there. Do you think you’d be able to give me a ride to my car?” I asked.

“Can’t for liability reasons,” he replied. “But you shouldn’t go in that water. It’s from Mexico, and they dump all kinds of stuff in there.”

Then he pulled away, leaving a cloud of dust in his wake. I snapped a few pictures of the rust-colored slats keeping the city of Tijuana separated from The Union. It looked like a scar on the skin of the land. The slats extended high into the air, blocking any clear view of the buildings on the other side. While I expected it to be imposing, I didn’t expect it to look so natural, as if it somehow belonged here.

After staring into the heavens trying to grasp the physical size of the barrier, I hobbled, still barefoot, to the other van. “Hello sir, I’m writing a story about border culture and The American Dream,” I said with a smile that maybe offered maybe a bit too much teeth. “I was wondering if I could ask you a few questions.”

This guy sported a big, jolly stomach and a crooked grin. I sensed he’d be a bit more open to questions than his grizzled counterpart. He looked at my bare feet and my mud-stained, purple gingham buttoned-down shirt with amusement. “Geez, I don’t know. I could get in trouble for something like that,” he said in a fashion that seemed obligatory.

I quickly shot back: “I don’t need to use your name.” That did it. “I really shouldn’t, but okay,” he said.

Then, he explained that winter slows his work as a border agent. In February and March, when the need for seasonal labor increases, he might catch 25 to 30 migrants in a day, but during these months he only gets around eight to 10.

“Did Trump’s election change any of that?” I asked.

During the first few months of Trump’s presidency, he said crossings slowed even more than usual, but then they started ramping back up. However, he added that since The Wall came to the River Valley patrol started catching a lot more crossers because “everything’s about time.” The few extra minutes it takes to cross this wall apparently make a huge difference when it comes to apprehending crossers, he said. I asked how he felt about stopping people from entering the country after they’d risked everything to come over. “I saw a dad running with his eight-month-old son, and you do feel sympathy for that,” he said with an intense look on his face. “But I’ve caught murderers and rapists, and there’s no sympathy for that.”

I pushed my luck and ask for a ride back to my car.

“I really shouldn’t, but get in,” he said. “But knock the dirt off those shoes first.”

He dropped me off just outside the nearly empty parking lot, avoiding any potential encounter with a superior. I thanked him and sat down at a nearby rock to brush off as much mud as possible before hopping into my rented, electric blue Mustang convertible, a treat incomparable to the old Nissan Altima I shared with my brother and sister back home. As I rode down the dusty path away from the sun, anticipating a much-needed shower, a police cruiser pulled up in front of me.

Shouting through his lowered side window, he asked: “Coming or going?”

“Going,” I responded.

“Good, because they’re blocking the road off with poo water.”

I can’t say I expected to walk barefoot through “poo water” when I decided to devote a week of my senior year of college to traveling 750 miles along the U.S.-Mexico border in search of some kind of truth about this constant campaign reference point, this national obsession, this eternal frame of my homeland’s success and failure — The American Dream. But maybe I should have expected it. When I think about it, dirty water seemed like a common backdrop in the images and rhetoric of this place — an unclear, unknown part of America, present enough to disrupt a narrative of perfection, hazy enough to foster superstition, inspiration, and fear. I definitely didn’t expect the blue Mustang though. But that was easier to explain: I was a middle-class kid on school break, about to graduate with a journalism degree from a private university in the Northeast. With my university’s financial assets north of $2 billion and their annual cost of attendance more than $70,000, I hardly felt swayed to forgo the chance to ride in style simply to save a couple hundred dollars in research cash that would otherwise go unused and end up back in the navy-gloved hands of Otto the Orange. So, with visions of Hunter S. Thompson in my mind and a thirst for seeking out whatever truths may lie in the Southwest on my agenda, I made my way to a part of this country which I heard so much about, yet knew so little of, prepared for inevitable enlightenment.

But before ever coming up with the idea to take such a journey, I had been thinking a lot about The American Dream. Like many in my generation, the professional future waiting for me seems bleaker than the one my parents knew. And the world itself seems to also be bleaker as well.

When Thompson set out for his search for The American Dream in Las Vegas in 1971, the U.S. was in transition. At the start of the Nixon presidency, America seemed to be in a state of backlash, a swift conservative rebuttal to the social awakening of the 1960s countercultures. Despite this, through the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s, America saw the end of the Vietnam War, the Disability Rights Movement, Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Movement, second-wave feminism, and the continued pursuit of Civil Rights issues through the Black Power Movement. And while the era had its issues, by the end of the Cold War things seemed promising. By the latter half of the ‘90s, the U.S. GDP grew by an average of 4.1% each year. Between ’93 and ’99 the median household income increased by roughly $8,000. And the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed above 10,000 for the first time ever. Fast forward to 9/11, and the world lurched, changed, darkened.

My generation only knows an era of terror; we’ve lived through the nation’s longest war for most of our existence. Doom is a familiar backdrop for us, living in an era of global warming. Today, violence exists as the norm, and anxiety is expected. Amongst Generation Z, those born between 1997 and 2012, just over one in four people will report fair to poor mental health. Three out of four experienced stress over mass shootings, and almost three out of five were stressed over global warming. With the internet increasingly taking over all aspects of life, we live life constantly connected, always exposed to pressures and new information. We stare at screens seeking escape and connection. We came of age bent over computer screens, being prepared by adults for the “digital world,” which we understand more about.

For a time, it seemed as if America was heading in a brighter, more welcoming direction. Same-sex unions were legalized, an African American man won election and lead our nation, and the issue of global warming seemed at the forefront of everyone’s minds. But today, the nation stands divided, ever at odds over right, wrong, and reasonable. Immigrants in general and the border in particular serve as a lightning rod for much of this divisiveness, and yet much of America knows nothing about its day-to-day realities — including me, someone being trained for a future in accurate and thoughtful reporting. With almost 60% of my generation reporting stress over the deportation and separation of immigrants and migrant families, I needed to better understand the realities of border life. So, I came to this place ready to learn from those who live closest to it.

At the border, I joined a legion of fellow travelers. In 2019 alone, people crossed the U.S.-Mexico border over 275 million times. For some of them, the trip consisted of a five-minute walk, but for others, their journey held things much worse than a sewage-water trench. However, despite the legal and bodily risks facing those pilgrims, the number of individuals crossing the southern border continues to rise as migrants seek out the promise of a better life ingrained in our country’s brand. And while we hear in the news their reasons for refuge and are taught in school about America’s history as the Land of Opportunity, for me, it’s difficult to imagine America as a place of dreams.

In my homeland, the top 1% control close to 40% of the nation’s wealth. Here, nearly a million and a half people celebrate their birthdays behind bars. In America, 15,000 people lost their lives to gun violence in the past year alone. A trip to the hospital after a heart attack costs an average of $20,000. And in those hospitals, Black women are three to four times more likely than White women to experience a pregnancy-related death — even if they have the same levels of income and education. Take all these factors and add an increasingly polarized government, and this country feels like a pretty grim place. And in fact, today, less than 50% of U.S. citizens say they’re extremely proud to be American. Today, the idea of The American Dream seems to be as elusive as Bigfoot, el Chupacabra, or the Loch Ness Monster — a thing of lore claimed to be seen by some, but not many. Stepping off the plane into the borderlands of San Diego, I wondered what glimpses of this elusive ethos I might see, my curiosity serving as my guide as I set off on this journey.

A dust storm must have swept through here and things never got cleaned up, I thought as I drove into Calexico, California, a city of about 40,000 on the border that connects economically with Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican state of Baja California. The buildings, which mostly stand one to two stories in shades of beige, tan and light mustard, seem built to be layered in dust. I find myself in this town on the day of the Christian Sabbath. With America’s founding engrained in religious freedom, the church always plays a role in policymaking, whether people notice or not. Churches also offer free provisions and services such as shelter, food, or legal counsel, affording individuals the access to exercise their rights. So, whether I felt liking singing hymns or not, I knew I needed to start my morning at Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church.

On my way, I saw maybe less than 15 people walking down one of the major commercial boulevards. Similar to the evening of my arrival, Calexico was 70 degrees and sunny; however, along with the pleasant news of sunshine, my iPhone weather app read: “unhealthy air quality for sensitive groups.” If the elderly fall into this sensitive group, then iPhone weather holds no sway. As I walked in and received a bulletin from an elderly gentleman in a white robe, I saw about 200 people sitting in the church’s 25 rows of pews, two-thirds of them looking well beyond 65. While the attendance seemed sizable for a 21st century religious institution, this service, the only one entirely in English, was only one of Guadalupe’s five Sunday masses.

The service began with a Latino man in a dark polo giving a speech about the “genocide of abortion,” asking members to pray for the “hundreds of babies who lose their lives in our nation.” After this, he directed us to stand as we welcomed Father Manuel Sanahuja. The church band started playing a hymn, and the man in the white robe slowly walked toward the pulpit, flanked by two young acolytes. He started his sermon with a reading from Isaiah on the love and wealth expected to come to Israel when the messiah returns. He went on to say that this wealth isn’t just for Jews, but all people, regardless of culture, language, race, nation or civilization, adding that anyone can be Christian when they meet Christ and offer their love. “God does not understand borders,” he said. “All at this table welcome immigrants.” After Father Sanahuja read the closing prayer, the band closed the service with “Joy to the World” before everyone dispersed back out into the dusty streets.

After church, I wanted to speak to the Father about his message. “God doesn’t recognize borders and for some people that disturbs them, but it’s true,” he said. Father Sanahuja, who immigrated to the U.S. from Barcelona, preached in Los Angeles for 49 years until last year when his superior asked him to make a change. “Here, it’s almost like a rural community, where religion is experienced in a different way,” he said. “They are not so sophisticated (like those in L.A.) to think of questions against religion…They tend to be much happier with themselves, more tolerant about certain things, more conservative about other things.”

Before I left, I asked Father Sanahuja about his thoughts on the current state of The American Dream. “The American Dream is a great dream that can still attract many people to come,” he said. “(But), the fact that (some of those in office) are always ignoring asylum seekers, making sure that they don’t get in, to me is a treason to The American Dream.”

I left the church to walk down the block and grab a Sunday snack from a weary red and white building called Donut Avenue. Walking into the place, which looked like a ‘50s diner that hadn’t been updated, or repaired, since that decade, I found that the name Donut Avenue failed to convey the full range of items available. The store sold everything from torta sandwiches to cheeseburgers and boba tea. The Slurpee machine looked tempting, but the sweet aroma of baked goods proved too powerful to resist. To get the goods, I moved around five people dining-in to take my spot behind three more people waiting in line. This seemed to be a good indicator of the donuts’ worth. When I reached the front of the line, the cashier greeted me in Spanish but quickly realized from my mangled reply that the transaction needed to be in English. I ordered a glazed donut for a dollar and took a spot at the ancient lunch counter nearby. The donut’s diameter surpassed the size of my face, and its texture almost met the ideal ratio of chewy to airy, skewing chewy ever so slightly. Before leaving, I waited behind two more people to buy a cinnamon sugar for the road.

Two major streets over, I found myself right up against the border. Here, I saw almost more people than I’d seen in the rest of the entire town. Spanish dance music filled the area, and the sidewalks flowed with people bouncing from shop to shop, constantly moving up and down the sidewalk, their shopping bags contently full. The buildings here seemed to be brighter than the others, as if the force of capitalism swept the dust away. Many of the shops seemed to sell clothing with each window or storefront featuring a mannequin dressed in an outfit that popped in terms of both brand value and color. Overall, the street served as a shining example of consumerism. However, among the commerce and lively chatter loomed the presence of the massive, cement U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Center. Hundreds of people waited on the other side to cross in, and a steady stream of others waited to cross back over.

After taking in all the commerce I could handle, I decided to make a final stop at the Mexican Consulate before ending the day. A locked door smacked me in the face, nixing my plans for a compelling interview and a much-needed bathroom break. Dangerously close to pants-wetting territory, I went against my better judgment and ventured to a nearby public park bathroom and almost walked right into a hooded man dressed in black sitting in the doorway with a needle in his arm. Feeling the same way one does after unceremoniously barging into an occupied yet unlocked bathroom, I immediately turned around and started in the opposite direction, catching two other men entering the bathroom out of the corner of my eye. I started internally debating whether it’d be better to risk the guy overdosing or risk him getting stuck in the prison industrial complex. After a few minutes time, I ultimately decided to call 911 and anonymously asked that an ambulance be sent to the location, not the police.

When I arrived back at my hotel, I ran into the hotel manager, Rosa, and told her about the man in the restroom. She told me she wasn’t surprised, that she’d seen something like that “almost every day,” sometimes at the hotel. “It’s the homelessness,” she said. Before heading to my room, I asked her what she thought about of the state of The American Dream in Calexico. “It’s not here no more,” she said.

The border continues to earn headlines, and most of the stories I hear seem fueled by the intersection of immigration and racism. Yet, outside of issues concerning immigration, little else about the border seems to bubble to the national level. I see a major reason for this being attributed to the decay of the news business. As a journalism student, I sit in class reminded every day of the issues facing the profession and its practice — the closure of newspaper after newspaper, the corrosive role of fake news, and a president who enjoys mocking (and occasionally encouraging violence against) reporters. The digital age has not been kind to the newspaper’s sources of capital. In 2008, the newspaper industry took in $38 billion in advertising revenue, but in 2018 that number dropped to $14 billion, according to The Pew Research Center. In 2008, the newsrooms employed 71,000 people, but in 2018 that number dropped to 38,000. With the internet cementing the 24-hour news cycle launched by network television in the ‘80s, the industry became saturated with information to the point where 58% of people say staying well-informed is difficult with only 38% saying it’s easy. In a time I never knew, people read their newspaper that appeared on your doorstep for the news of the day and then they welcomed a few monthly magazines that offered in-depth takes on that current events and possibly some stories that spoke to an interest or hobby.

But with today’s fast information and free online content, almost 75% of those in my generation spend their free time online while only 25% devote their time to reading newspapers, magazines, and books. Most accept their information quickly and have been trained to respond fast, so much so that my generation’s average attention span clocks in at eight seconds. But for now, I remain optimistic about the information still being dispersed at the local papers. So, I decided to introduce myself to the town of Nogales by taking a trip to the Nogales International newspaper.

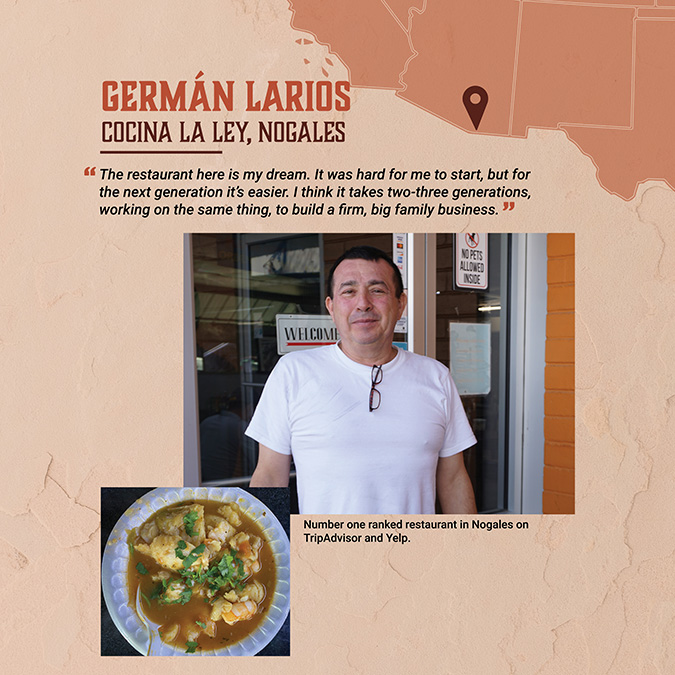

The paper sat in a strip mall on a side street off the main road. Through the glass door sat a few cubicles, stacks of paper, and two or three side officers. The space occupied less square footage than a two-bedroom apartment. A secretary introduced to me to the paper’s Managing Editor Jonathan Clark, a tall, middle-aged man with white hair, who agreed to fill me in on the area.

I learned that Nogales is a town of roughly 20,000, but its sister city south of the border, also named Nogales, boasts a population of about 230,000. The town’s unemployment rate ranks much higher than the rest of the country at 9%, and almost a third of the population live below the poverty line. Despite the economic challenges, Clark said crime is pretty low and that last year the city only experienced one homicide, a domestic violence situation. That event aside, he described the city as a family-oriented community. “There’s a lot of pride around Nogales High School,” he said. “You see, a lot of the people wearing the school colors, and the sports teams are popular.”

After we finished discussing the state of Nogales and the local press, Clark showed me around the office, where I saw more cubicles in the back and a wall of awards. He introduced me to Genesis Lara, one of the paper’s reporters who grew up in Nogales. I asked her what it was like growing up on the border, and she said that’s a question she gets a lot. “One thing that I always think is very different from everyone else’s childhood or upbringing is that you literally cross to another country every single day if you have family,” she said. Growing up, she and her friends would spend time partying and shopping across the border. “It’s very fluid,” she said, adding that oftentimes people cross with just their driver’s license. Shocked, I asked her how that was possible, assuming U.S. Customs would never allow such a thing. “It’s not really an issue here in Nogales,” she said. She knows several people who’ve never had a passport and yet cross back and forth often with just a driver’s license. I asked Clark if he knew people who crossed that easily, and he said he did, sharing some of Lara’s amusement at my shock. I guess The Wall was a little more porous than I had thought.

“You should go across,” he suggested. “Might add something to the story.”

Sounded like good advice from an editor. So, I took it. And in a minute’s time, I walked through the metal detector, across the turnstile, and stepped straight into Mexico. “¡Bienvenido!” an official said as I entered. Quick would be an understatement to describe the process of getting through, and it could have been even quicker if I hadn’t entered behind an elderly woman who might have thought she was walking across a catwalk in her fuchsia tracksuit. The vibrancy of Mexican Nogales stood unmatched to the dust-covered neutral colors of other spots I’d visited. The buildings, painted in eye-catching colors like pink, yellow, and turquoise, stood twice as tall as their American counterparts. The foot traffic outnumbered that of Calexico and American Nogales combined, and the density of automobiles substantiated Mexican Nogales’ claim as a border metropolis.

The first businesses I saw were three clearly labeled dentist offices and more than three clearly labeled farmacias. While the American side greets visitors with capitalism, the Mexican side greets them with pain relief. As I walked through the worn, cement streets I saw people dressed in light colors waving to each other and shouting friendly greetings from rooftop balconies to those below. The scene provided an aura of friendliness that you only find in a rural town or a ‘50s sitcom. Not far into my walk, the side street started filling up with tin sculptures of horses, rabbits, deer, and other animals. A fast-moving shopkeeper with a goatee and a rattail, dressed in blue jeans, a rosary and a black calf skin vest, sped toward me with a greeting. It didn’t take the man, who called himself Simon, long to switch from Spanish to English when he heard my reply. Eager to sell, but also eager to chat, Simon enquired about my visit to Mexican Nogales and soon learned about my mission to find The American Dream. Amused by my curiosity in the border, Simon, who said he was in his 50s but didn’t look it, told me that in all his years, he never needed documentation to cross into the U.S. When he wanted to visit America, he simply traveled to a section of The Wall at the top of a nearby hill, jumped over, hung out with family, then hopped on back. He said he’s been using this method for 40 years and has had no issues. I pushed him a bit, asking if he was serious, but he stood his ground, adding that if he lived near El Paso, then it might be a different story.

After caving and purchasing a $13 silver chain, I moved toward the heart of Mexican Nogales and happened upon a towering gray, perhaps once white, Catholic church. A shopkeeper told me that many of the tired, weary people dressed in coats and denim sitting inside the building and standing around it were refugees from the Northern Triangle, a reference to three Central American countries (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador), seeking refuge as they wait to cross into America. Trying and failing to communicate with them in Spanish, I moved on and came across three young girls, each younger than 13, who noticed my camera and asked for a picture. A couple then joined us, and the husband asked me to take a picture with his wife. While Nogales, as a border town, likely receives a flow of White American travelers, I seemed to stick out on that particular day based on the giggles and stares I received. Between my camera, Aviators, and powder-blue oxford, I understood their reactions. So, I decided to embrace my visitor status and paid two dollars to sit on a donkey standing outside the market as a photo prop for tourists. His keeper told me his name was Obama and he wore a straw hat. Just before taking my photo, the keeper placed a sombrero on my head and a few locals passing by laughed at me.

After dismounting Obama, I made my way closer back toward The Wall, searching for people willing to share their stories of immigration. I ran into a talkative, but not pushy, street merchant who told me a group of asylum seekers waiting to enter the U.S. were arrested by Mexican authorities a few hours earlier. When I got to the place where they’d been arrested, I saw a young couple dressed in layers holding two suitcases flanked by two young boys and two young girls, all of whom looked younger than 10. I tried speaking to them in Spanish, but once again failed. Fortunately, the merchant agreed to translate.

The couple told me they fled from the Mexican state of Guerrero, an area my translator said is incredibly dangerous and the U.S. lists as a “Do Not Travel” zone, in the same category as Syria and Afghanistan. The man said that back in Guerrero he worked on a ranch until the local cartel demanded he work for them by sabotaging certain roads so they could sell weapons with greater ease. Left with the options of death, a life of crime, or fleeing the state, the man chose the latter, uprooting his family to seek a new life in the United States. The family planned to cross the U.S. border through customs; however, they’d been waiting a few days and were still unable to declare asylum.

After hearing their story and expressing my hope for their safe passage, I left, walking through the entrance to U.S. customs right next to them, carrying much guilt. Within 10 minutes, I stood in front of a White border official who asked why I’d visited Mexican Nogales and to see my passport. I told him my reason for visiting and said I’d forgotten my passport but had my driver’s license. And like that, without official identification, I returned to American Nogales and walked back to the hotel.

But I struggled to shake that family from my mind. It seemed so unfair that they had to sit there, waiting while others could cross over in a matter of minutes. It made me think about the privileges of U.S. citizenship. Even if they possessed the means to travel more efficiently and lavishly, by virtue of being Mexican citizens they could only travel to 158 countries visa-free, while I could travel to 184. Yet with their passports, they’re in a much better situation than someone born in Ethiopia. An Ethiopian passport only affords entry into 43 countries visa-free. And while Americans may think our country provides the best of everything, we can’t say we have the best passport. Japan tops that list, ensuring access into 191 countries visa-free. While the meaning of freedom could be debated, only someone wanting to lose said debate would argue that movement isn’t a part of freedom, and some country’s citizens, by virtue of birth, get to be freer.

So, as I waltzed past that family into the U.S. feeling guilty, looking back, that guilt came from my abundance of freedom to the point of recklessness, and their lack of freedom to the point of captivity. And perhaps this sense of freedom, associated with movement, informs our sympathy for displaced refugees. As a privileged individual in a wealthy country, I control my movement while that family cannot. And that is just one of the many reasons why I, have things better than they do — by virtue of birth, something I did nothing to deserve at all.

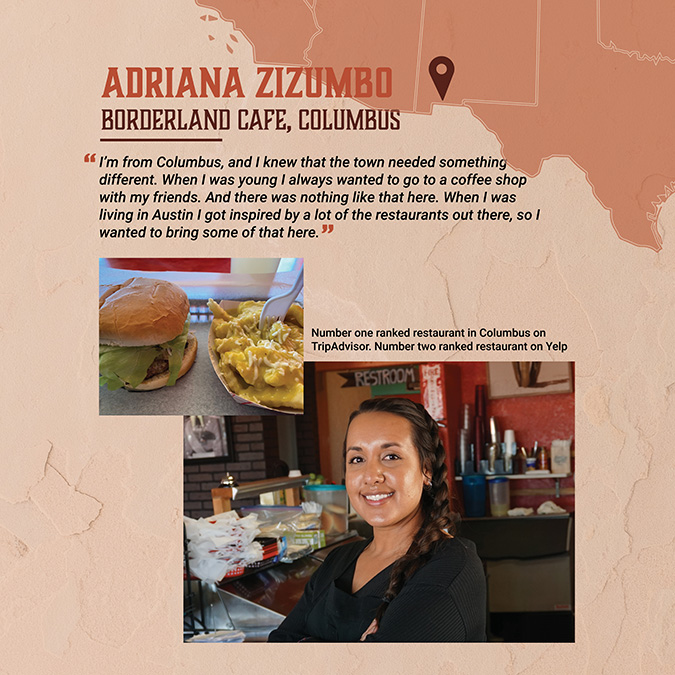

When I created my itinerary, it seemed important to stop in a town named after the man who “discovered” America. In the spirit of its name, I imagined Columbus, New Mexico would offer at least a few things for me to “discover.” Whether that be a new insight into America’s relationship with Mexico, or a different perception of The American Dream, I was eager to learn.

Of all 50 states, New Mexico ranks in the top five poorest, making it the only state on the Southern border to crack the top 15. Here, I sought to explore the vitality of American exceptionalism in a place all but forgotten.

While I expected the town to be small, I didn’t realize how truly “small” could be until I arrived. The center of Columbus seemed to be comprised of roughly 20 short, stucco buildings painted in shades of tan, white and yellow. Most of the road I drove on was paved, but some side streets were dirt. When the GPS finally alerted me of my arrival at Los Milagros Hotel, I saw a two-story rectangular building, painted deep mustard on the front and blue on the sides. A yellow school bus sat parked in the big, empty lot to the building’s left, and five parked cars lined the building’s font.

As soon as I walked through the door of the hotel, the hotel’s owner Philip Skinner introduced himself. Philip, dressed in flannel, jeans, and a baseball cap, stood around 5 feet 7 inches, walked with a slight hunch, and could’ve been anywhere in his mid-70s to late 80s. He quickly gave me the key to my room and started showing me around the homey hotel whose detailed western décor made it feel more like staying at a relative’s place than a hotel. Philip asked what’d brought me to Columbus. I told him I was a journalist on a hunt for The American Dream and returned the question by asking him what types of guests usually stayed at Milagros. “It’s very eclectic,” he said. “We have construction guys working on The Wall, it’s a two-year project, 50 miles of a wall. We have you and then a lady bicycling across the country. We get people going from the United States visiting family down in Mexico. We get Mexicans coming up here visiting family in the States, we get business people, it’s just very eclectic.”

The next morning, after a night of driving through the neighboring Mexican town Puerto Palomas with Philip as part of his quest to flip a 65-inch Roku TV, I woke up to fresh yet dusty morning air. The sun shone overhead, warming the desert to 65 degrees.

As I headed toward the main commercial street, a few cars passed by, but I saw no people. Walking down the main street of Columbus, Broadway felt like walking through a portal back in time. The buildings included the Tumbleweed Theater, a saloon painted a vibrant blue, a community center, and a library. According to Philip, the library is one of the hippest places in town. The Friends of the Library club and a robust array of rentable movies make it a social hub. Just down from the business strip sits the town hall where I met Columbus’ Mayor, Esequiel Salas.

Salas was an earnest-looking man with a rosy-cheeked face and piercing dark eyes. He wore a white wide-brimmed panama hat, a red shirt, and gray blazer, an outfit fitting of a man of his stature. I discovered that Columbus is a town of about 1,600. The unemployment rate stands at about 12%, and almost half the town lives below the poverty line. Speaking toward these issues, Mayor Salas said the town struggles most with infrastructure. “This little village has been forgotten and neglected for decades,” he told me. “But we have rolled up our sleeves, we are getting to work, and we’re not waiting for anybody to come and do anything.”

When I asked what The American Dream looked like in his town, Mayor Salas said it was similar to most other towns along the border: “People just want to live better lives, make a good living, and take care of their families.” Before I left, Mayor Salas mentioned that though Columbus is small, with a total area just under three square miles, it boasts a big history — in 1916, Pancho Villa raided the town in what would be known as the Battle of Columbus. Villa’s raid on the town led President Woodrow Wilson to send 10,000 troops to the area, launching the search for Villa known as the Pancho Villa Expedition. The U.S. army ultimately failed to catch Villa, and the town of Columbus began its decline.

After walking through the whole town, I decided to spend the remainder of my day south of the border. Like Nogales, I crossed the border in minutes, walking out to the town’s small square with a tall, silver statue of a rearing horse at its center. In daylight, Palomas, population 4,700, looked even more vibrant. Cars and motorbikes passed up and down the streets, and a few dogs trotted along looking for food. Some of the first buildings I saw sold liquor, offered dental services, and sold medications. In the light, I saw a range of colored buildings: purples, oranges, greens and blues. Unlike the main street, residential streets lacked pavement. Most of the houses looked like they held less than four rooms, featured gray or faded white exteriors, and sat under tin roofs. Shoeless children ran up and down the streets. Eventually, I stopped aimlessly walking and headed to the Pink Store, a place Philip pointed out the night before, for an early dinner.

An impressive array of Mexican liquor and knick-knacks — sombreros, cactus statues, multicolored parrot statues — crowded the front of the store. I resisted a powerful souvenir urge and headed to the restaurant, where a smiley maître d’ quickly sat me down and a waiter immediately arrived with a basket of chips and three types of salsa. Noticing the menu’s prices meant I could afford a steak dinner, I ordered ribeye al ajo de porfirio with fries and a Mezcal margarita, all for less than $20.

As I sat enjoying the power of the American dollar and the frailty of the Mexican peso, my mind drifted to the purpose of my journey. Here I was, as a privileged glutton, taking advantage of my country’s economic power, while people along this same border risked their lives to enter the country I call home. I thought about how back in San Diego I met a tiny woman named Maria Merida who used to work as a housekeeper in Guatemala. She fled her country after her daughter was abducted and killed. She’d been forced to leave after those who took her daughter later threatened to also take her son, Fernando. When I met her, she waited in line at a food bank. As an undocumented citizen, she was not allowed to work and made her living selling drinks on the sidewalk. For Merida, The American Dream meant survival.

I thought about the children of the father and mother from Guerrero with the four little kids. If they earned refuge in the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave, I doubted that the couple would ever have access to the privileges most Americans enjoy. Like Merida, their days would probably be spent just trying to survive. But those children — maybe they would have the chance to aspire for more. And I suppose for a parent that’s a dream in itself.

As the sun retreated, I returned to Los Milagros with a tallboy Dos Equis in hand, grabbed a seat on the common room couch and struck up a conversation with the two men working on Trump’s Wall. The two guys — both identifying as Mexican in heritage and living in Tucson — had been staying at Philip’s hotel for more than three months. One of the guys, named Marco Lopez (goatee, about 5’10″, dressed in a khaki shirt and blue jeans), worked as a welder. His shift each day lasted from 6:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. Before working, Marco and the guys, who he said were almost all Mexican, did a few stretches and listened to a safety speech. Then, they crafted around 35 panels before the end of their shift.

Before working on The Wall, Marco worked for 14 years in a Tucson mine where he made half of his current salary. “I’m not with it politically,” Marco said. “But it’s a job.” And while he expressed doubt about The Wall’s effectiveness in keeping people from entering the country, he said it’ll serve as a better deterrent than the Czech hedgehog barriers The Wall replaces. Eventually, our conversation turned to journalism, Mexico, and the Peyote Way Church of God, and we slowly transitioned to the dining room where two middle-aged, all-American truckers sat enjoying a bottle of whiskey.

The truckers, Matt and Arnold, exuded a huntin’ and fishin’ type of manhood. And they shared some memorable stories of their wildlife takedowns to back up said masculinity. Matt, who wore a black T-shirt, black cap, blue jeans and suspenders, sported a silver beard and carried about 300 pounds on his 6’2” frame. Arnold, dressed in khakis, boots and a bright orange shirt, had a mustache, stood taller and weighed about 60 pounds less than his friend. The truckers said they too were working on the wall and complained that they got paid by the load, not by the hour. So, when they worked, it was a race against time to deliver as many truckloads of supplies to The Wall’s building site as possible.

Like the welders, they’d also been calling Los Milagros home for the past few months, bringing their own grills and decking out their campers parked in the back. As we chatted about the border, politics, and Trump, whom the truckers respected in a manner quite differently from the welders, Matt pulled out a handle of Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Fire and offered us all a drink. Glasses full, all drawn to this place in one way or another by Trump, we facetiously toasted “to The Wall” before choking down the flaming cinnamon. While each of us were from different generations, lifestyles, and backgrounds, we all sat in that tiny Columbus Hotel because of one thing — Trump’s Wall. And, support it or not, that in itself was pretty phenomenal. Soon, the conversation turned from politics to workplace minutia, and I remembered my morning started at 6 a.m. Sipping the last of the whiskey, I thanked the crew and headed to bed.

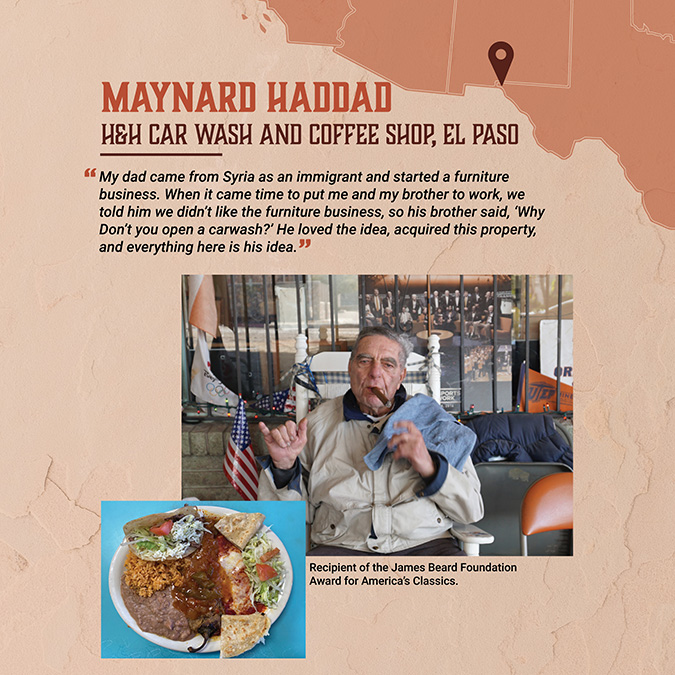

As I headed into El Paso, my flight back to the Northeast looming, I decided to take things back to where they started — The Wall. Though roughly 750 miles away from the section of wall set behind the sewer trench, the same ominous presence presided over the 30-foot tall metal slats separating El Paso from Juarez. Aside from the white patrol vans looming in the distance,

The Wall stood at least a five-minute drive from any nearby life, giving it a reigning presence over the area it inhabited. As I walked closer, long shadows reached beyond the slats, extending over me. Plastic cups, crumpled papers, and sheets of metal littered the area at the base of the beams, and as I drew closer, I heard a rooster crowing in the distance. I worked my way close enough to stick my hand through, and as I did, I peered into Mexico and saw two barefoot children — a boy, dressed in black, and a girl, dressed in pink — throwing a ball and running around the nearby Juarez neighborhood. I thought about how odd it must be to have The Wall in your backyard. I wondered if they knew the meaning the structure possessed, if they ever thought about crossing, if their parents wanted to cross. Like the children from Guerrero and little Fernando, their futures seem to rest in the hands of those whose compassion and empathy has long been skewed from the blissful tolerance only found in a child. I’d spent 10 days searching for The American Dream and saw it everywhere I went, and simultaneously nowhere at all. I waved to the kids, and they waved back. Then, after a pause, they returned to their game. I continued to look for moment then turned back to the Mustang, hopped in, and drove away.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Lucinda Stroll for the travel dish card illustrations and Tanner Hogan for the location header illustration featured in this project, Brooke Kato for copy editing, and Zoe Davis for photo guidance. Also, thank you to Melissa Chessher for overseeing this project from start to finish, Jon Glass for production guidance, Jack Radford for being the first reader, and Diane Weiner for providing extensive feedback. Lastly, thank you to the Reneé Crown Honors Program for funding this opportunity.