“Do you even know how smart I am in [native tongue]?”

“Do you even know how smart I am in [native tongue]?”

Students shed light on the diverse and often unseen challenges in the pursuit of academic success with language barriers.

Syracuse University is the home to about 4,000 international students, about 14% of the student population.

All of these students have varying degrees of proficiency when it comes to speaking English. But an even bigger shocker can be the barriers they face to understanding American jargon.

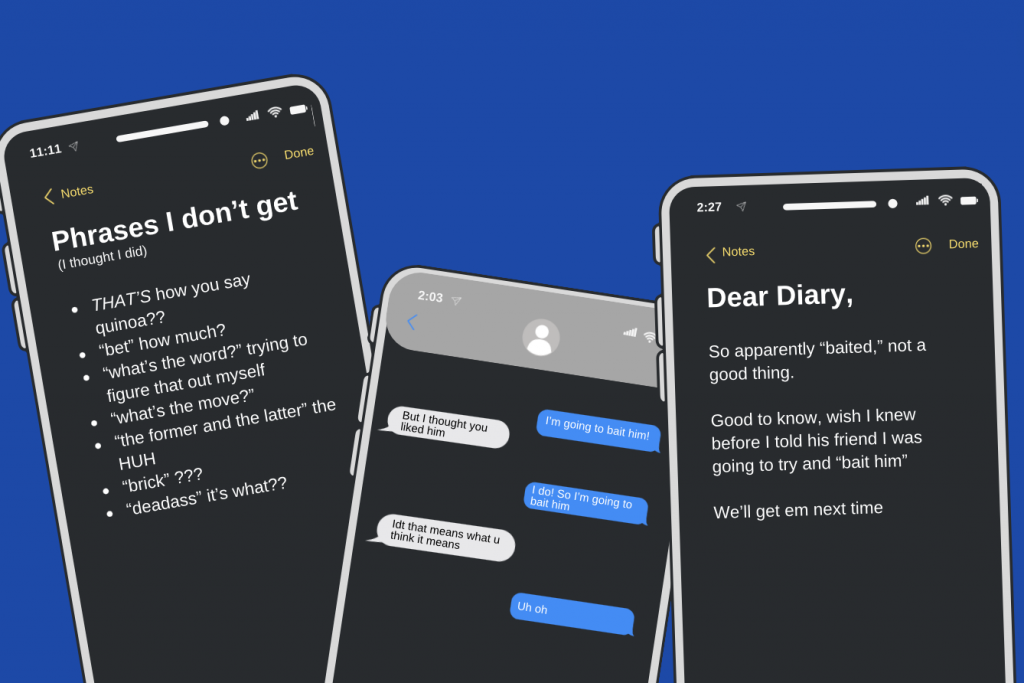

Language barriers go beyond the four walls of a classroom and into daily life. International students are prone to struggling when engaging in informal conversations and navigating the subtleties of social interactions. The American vernacular, in all its glory, can be a challenge even to those with a strongest foundation in English.

Connecting to a community completely foreign and achieving acceptance has many layers to it. As a generation, we have composed a web of obscure jokes, carefully curated niches and extensive slang. This causes trouble for those who aren’t up to date on these in regular social interaction.

Lisa Wolkers, a magazine, news and digital journalism junior from the Netherlands who is currently studying abroad at SU, found it particularly difficult when it came to classes.

It’s become apparent that a person whose first language isn’t English will face a good amount of trouble learning American journalism and English grammar. Wolkers feels like she’s struggling to catch up and turn in work that’s up to par with her peers. She is current in a copy editing class where she has struggled.

“The professor will tell me my work shows English isn’t my first language,” Wolkers said. “I’m trying, but she’s right, it’s not.”

Expert Voice

Çisem Arda, a SU Fulbright Scholar and Turkish language instructor, has been an English tutor since 2019. Arda observes language hardships students face both inside and outside the classroom.

“They [international students] felt like their writing and speech looked and sounded childish,” Arda said. “They were kind of ashamed of their writing and speaking at the same time because even though they had lots of ideas in their own mother language, they couldn’t transmit it.”

Arda said she found most international graduate students feel as though their vocabulary is not that of a graduate student but of a high-school student. Often, instructors suggest they go to writing centers.

“Even though they benefit from going to writing centers, they find them a bit superficial because they just give them general feedback,” Arda said. “Most students don’t find this help that meaningful. Some are ashamed of going because they’re graduate students.”

She continues saying that some instructors were not very accommodating and would tell students to go back to these writing centers, though they’d already gone. She believes that instructors could be a lot more understanding of these circumstances.

“The United States is a top destination for international students to study on a graduate level,” she said.

International students should have the intention to pursue help from the mental health service. Schools could employ some bilingual psychiatrists to help international students better open their hearts. Schools can also carry out some lectures, emphasizing the importance of pursuing help with mental health care by students themselves. Research suggests that, compared with domestic students, international students are less likely to pursue psychological care.

Data Talk

The 2021 issue of The Journal of American College Health reported that international students who are aware they need mental support are 17.6% lower than domestic students.

Up to 50% of domestic students had considered mental consulting, while only 1% of international students thought of counseling support. In reality, more than 30% of domestic students have accepted mental health services. Less than 17% had accepted mental services.

“For international students, opening up to people or mental health professionals is completely different from American students,” says Zenith Tandukar, Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota, who came to the U.S. from Nepal in 2009 as an undergraduate student.

“At least from my country, we are very private people. We do not really like talking about our problems.” Tandukar believes that mental health supporters should be aware that more “people who we are comfortable talking to” providing mental health services are needed.

Academically, language barriers can stand in a student’s way in more ways than one. Speaking, as Arda came to realize, is one of the biggest hardships a multilingual student faces.

Most classes, in any field, calculate a participation grade at the end of the school year, but does participation equal engagement? Participating in class discussions can be a formidable challenge for students whose first language isn’t English, often impacting their participation grade.

The language barrier introduces a layer of difficulty for an otherwise simple task, as these students grapple with expressing their thoughts and ideas in a language that they’re not native to.

According to the Atlantis Press on Mental Problems of “Language Gap” for International Students. “This makes it hard for them to understand the study tasks and the office hours with their professors…International students did not have confidence in oral English and faced many serious learning problems.”

Fear of making linguistic errors, combined with the anxiety of being misunderstood, can create a significant boulder that stands between them and active class engagement. These students may possess a profound understanding of the subject matter but find articulating their insights verbally to be a difficult task.

“Some students get shy because they fear mispronunciation. They think they cannot pronounce words that clearly and this makes them feel ashamed of speaking and sharing their opinions,” Arda said. “The pressure to communicate fluently in real-time can evoke nervousness and self-doubt, inhibiting their willingness to speak up in class.”

Pronunciation is a significant struggle when learning English in “another country, through textbooks,” Arda says. She expresses that there is a difference between learning a language by reading it and hearing it. She claims if the first time a person hears certain pronunciations and accents is in action, it will be harder for them to pick up what’s being said and register the accent.

Being bilingual has many benefits, according to the National Institutes of Health. Being bilingual, the brain’s executive functions are enriched, these functions encompass concepts like working memory, emotion regulation, focus, self-monitoring, etc. The benefits could easily outweigh the disadvantages, in theory, but students still have a bit to say on the challenges.

Adriana Albizu is a junior at Syracuse University who was born and raised in Puerto Rico. “I wouldn’t have it any other way, but I think knowing two languages, they scramble together sometimes in my mind. I swear, for a second, I can’t speak either properly.”

“I feel like I am smarter in Spanish, but people here don’t know that, my professors don’t know that. I’m never giving my 100% because that would mean speaking Spanish,” Albizu said.

We proceeded to briefly discuss a monologue once said in the TV sitcom, Modern Family, by a Latina character, Gloria Delgado-Pritchett: “Do you know how frustrating it is to have to translate everything in my head before I say it? To have people laugh in my face because I’m struggling to find the words? Do you even know how smart I am in Spanish?”

Arda argues that this issue not only affects one’s social life but mental health as well.

“You feel like you’re using your brain on maximum,” she said. “They feel like they’re constantly missing something, some important information that they are not aware of.”

She recalls a six-week activity in a class where she had to teach English to Colombian adult students. Arda was matched with two native speakers in her group who spoke English. She felt like she had an extra task of understanding her teammates’ English when they’d use phrases she didn’t understand.

She used “drop the ball” as an example. “I was trying to understand them, I was trying to understand their opinions, while trying to give them my ideas and reflect on their opinions. Also taking notes at the same time to write lesson plans later on.”

“Because of our language barrier, some classmates don’t want to work with us,” she said. “They don’t socialize with us after class unless they’re really willing to understand the culture.”

Struggling with the English language can cause both educational and social shortcomings for a student. To connect with people, there’s slang and jokes one must know. Like a secret language, some keywords act as a pitch only some with the cheat sheet hear. Every generation has a unique mental dictionary that makes it harder for outsiders to infiltrate successfully.

There’s a sort of comedic relief in hearing phrases and feeling like you’re being pranked, and more so knowing you’re not the only one.