Experts worry attack ads distort truth without lying

Negative political spots can help voters better understand candidates, but some stray into disinformation and undermine democracy.

man with a cane gets punched in the face and falls to the ground. Another man gets shot at point-blank range in front of young children. Masked robbers smash a shop window with sledgehammers.

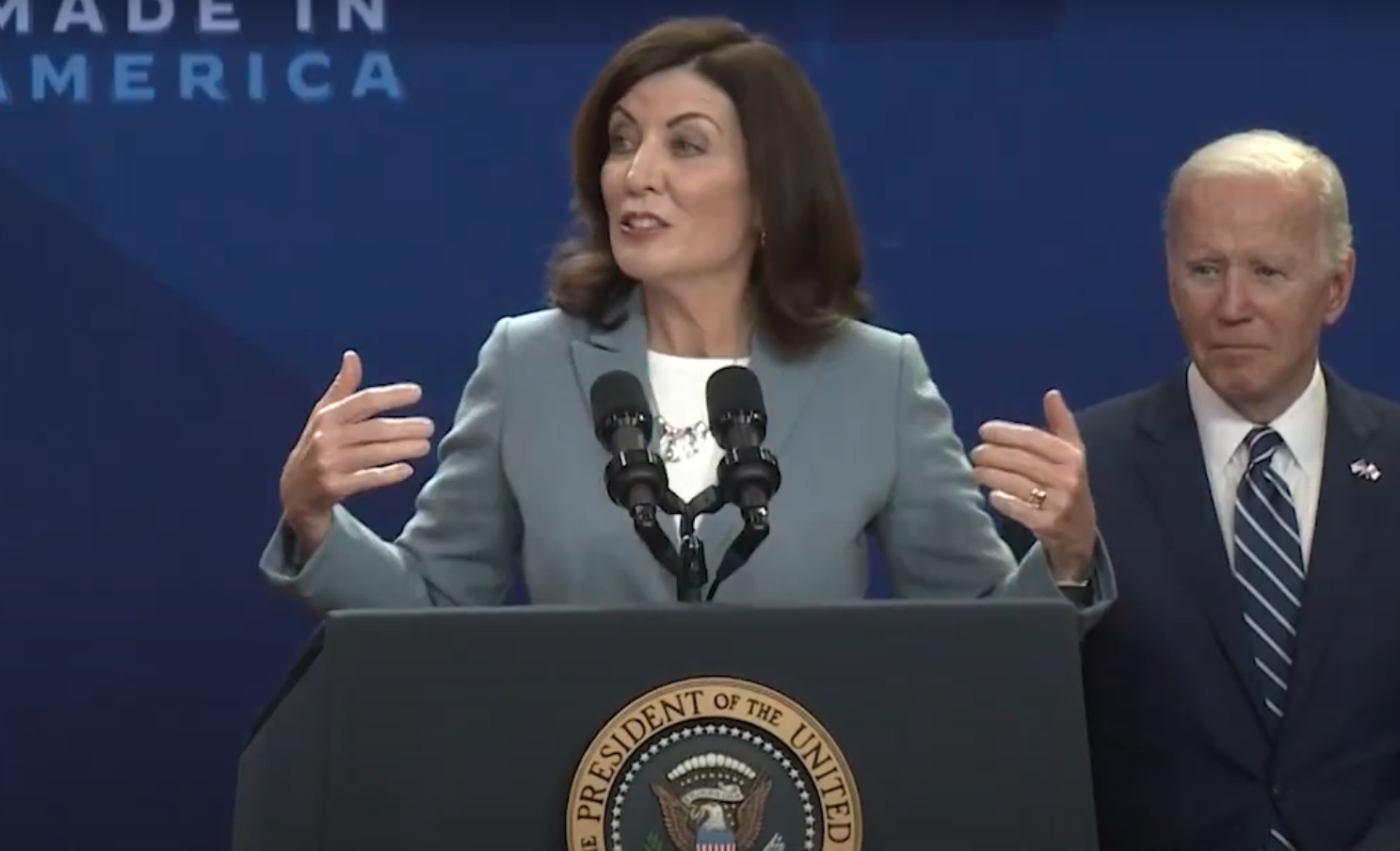

The attack ad against Gov. Kathy Hochul has been running on repeat throughout New York this fall. A montage of violence, the ad lays the blame for higher crime rates in the state squarely on Hochul and her support of controversial policies such as bail reform.

The ad, which contains enough violence that YouTube requires viewers to verify their age before watching, at once asserts facts while also creating a misimpression that bail reform is the sole driver of crime rates in New York, say experts like political scientist Grant Reeher.

“It’s true that crime went up, but the question is how much can you point to this specific policy as a cause of that?” said Reeher, a professor at Syracuse University and director of the Campbell Public Affairs Institute.

As the national debate rages over the “big lie” and what counts as legitimate political discourse, the ad against Hochul and ones like it beg the question: are attack ads spreading misinformation and harming democracy, or helping inform voters?

The answer, it turns out, depends on who you ask. Another expert at Syracuse University, Reeher’s colleague Emily Thorson, said negative ads are good for democracy because they help voters understand the downsides of voting for a candidate.

“Often negative ads are actually very informative,” Thorson said. “They tell people about the candidate’s position including unpopular policies, and that’s what people need to know. You can make an extremely negative ad about a candidate that is still very informative about them.”

But Reeher says attack ads can go too far and become disinformation. He pointed to an advertisement that attacks Hochul’s opponent in Tuesday’s election, Republican Lee Zeldin. The ad correctly states the congressman’s support of policies at the federal level that would make it illegal for women to get abortions even in circumstances of rape or incest. It then concludes Zeldin is “dangerous and extreme” and ignores his statements that he would not outlaw abortion in New York if elected governor.

“What the Hochul campaign is focusing in on is what his beliefs are about abortion,” Reeher said. “Now, that’s fair to talk about because when you run for office, what you think is important. Where I think the ad gets into disinformation is making the leap from that to explicitly asserting something that Zeldin has said he doesn’t want to do, which is to change state law.”

On the streets of Syracuse, nine citizens spoke to The NewsHouse and said they were sick of the negative ads.

“I appreciate them all but they are a bit much at this point,” said Kathy Sims-McDaniels, who was visiting Syracuse from Atlanta. “I see one after another after another. It tends to be a lot.”

Sims-McDaniels isn’t the only one who has noticed the sheer volume of political advertisements, thanks to a record-breaking spending spree by candidates and their proxies. The two parties will spend an estimated $9.7 billion on ads this election cycle, according to the nonpartisan firm, AdImpact.

“There’s a tremendous amount of money that is influencing elections,” said SU professor and legal expert Nina Brown. “It allows for this distortion of the marketplace of ideas.”

Another distorting factor is that, in the typical 30-second ad spot, campaigns go for bold rather than any sort of nuanced discussion that accurately portrays the world. Zeldin’s ad against Hochul, for instance, contains at least one clip of violence fact-checkers say actually took place in California.

Should misrepresentations such as linking New York to a crime that happened in California be out-of-bounds? Perhaps, but the FCC does not fact-check political ads for accuracy like they do for commercial ads. The Communications Act of 1934 determined broadcast channels have “no power of censorship” over “legally qualified candidates” for office.

Brown, who teaches communication law at the Newhouse School, says there is good reason to have an open marketplace of ideas. “One of the reasons why we protect false political speech is this idea that the marketplace of ideas is going to correct false statements, and that the truth is going to emerge,” she said.

But she added it is less clear this approach works in 2022 when you combine the obscene amount of money fueling these ad blitzes and newer, more targeted communication channels on platforms like Facebook.

“When you create echo chambers on social media, you essentially create mini marketplaces where there’s not an exchange of ideas.”

“When you create echo chambers on social media, you essentially create mini marketplaces where there’s not an exchange of ideas,” she said. “There’s just a reinforcement of one idea, and social media algorithms are designed to create these mini-echo chambers.”

Researchers from New York University and a university in Belgium found that an alarming number of political advertisements on Facebook contain false information, despite Facebook’s claim that it has new systems in place to prevent the spread of political disinformation on its platform.

“It was quite concerning that Facebook makes a lot of errors in classifying these political ads,” said Victor Le Pochat, the lead author of the study, which Facebook has criticized. “We saw more ads that were missed than actually caught by Facebook systems.”

The consequences of misleading political advertising get ratcheted up even further now that the very foundations of the electoral system are being challenged by candidates who reject the outcome of the 2020 presidential election.

“The election denial movements, while akin to negative advertising, is taking it to another level,” said Dustin Czarny, Onondaga County Democratic election commissioner. “I think that’s what scares me the most.”

Proposals like the Honest Ads Act might help the landscape of political advertising, but thus far the bill has failed to gain traction since it was first introduced in 2019. That leaves voters to fend for themselves as they try to determine what’s true, what’s misleading, and what’s a flat-out lie.

All nine voters say they prefer advertisements that focus on a candidate’s strengths and qualifications rather than negative attack ads like the ones dominating the 2022 election cycle. Syracuse resident Alex Silver says he also finds qualification-based ads easier to fact-check.

“I dig a list of accomplishments, stuff I can actually check,” he said. “I know people do things wrong, but the positive ones I can actually check and see if they are right.”

But Reeher says the goal of negative ads isn’t to inform but rather to discourage people from voting. “The overall effect is going to be more people (saying) ‘the hell with the whole thing. I’m not voting. This is disgusting. I am not participating in this,’” he said.

“The problem with the attack ads,” Reeher added, “is that the ultimate effect is just to make people turn away from politics in general, … and that does not serve our democracy well.”