The Digital Cyber Mule

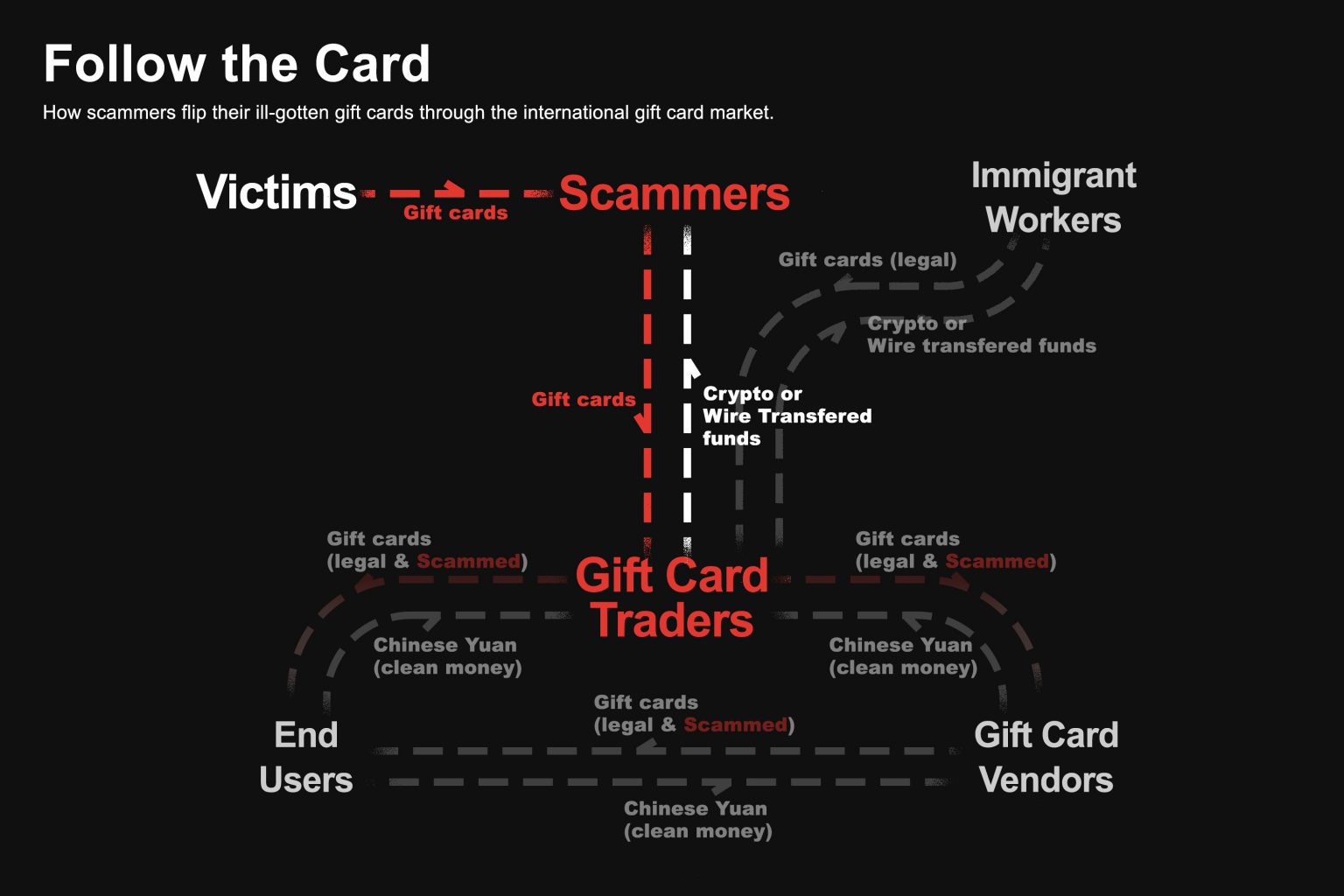

Gift cards play a key role in the scam economy, providing both a target for theft and a mechanism to turn ill-begotten gains into cash.

cammers’ ability to cash in stolen gift cards relies on a complex global market that also includes Chinese gamers and migrant workers sending money home.

China banned Google services in 2014. But with VPNs to hide their location and Google Play store gift cards to purchase games and apps, many Chinese users find ways around the restrictions.

It’s not always easy. In 2021, gamers with user names like “ultramancliub” found that they could no longer redeem their gift cards, even though they bought them from Taobao, an online Chinese retailer sometimes compared to Amazon.

“It warns me the balance can only be used within the U.S,” ultramancliub wrote on the virtual private server forum, hostloc.com. “My balance is locked.”

Another user chimed in: A recent change meant the cards had to appear as if they were being used inside the United States. “The rules are stringent these days,” user “jqbaobao” remarked.

Chinese mobile game enthusiasts have long purchased gift cards from third-party vendors to replenish their Google Play credit. It allows them to buy games without owning international credit cards. Workarounds like this are necessary for the unconventional Chinese market after Google stopped offering services in China, first in 2010, and then sporadically until China banned the service in 2014.

Since then, Chinese users have been forced to adopt dodgy methods to bypass the country’s rigid internet control. VPNs, or “ladders” as Chinese netizens call them, are a must to breach the Great Firewall. The VPN allows users in China to appear as if they’re in the U.S. The method is far from fail-proof, but it allows many Chinese gamers to get their hand on a functional Google Account and access to the Play Store’s huge library of mobile gaming titles.

What these gamers didn’t realize in 2021 was that in an effort to confront an entirely different type of user – the scammer – Google was about to “geolocation lock” its gift cards. The new controls would make it far more difficult, although not impossible, for Chinese users to use their gift cards. The changes also helped expose the gamers’ unwitting role in helping scammers turn gift cards into cash, and shed light on the difficulties of preventing money laundering when the transactions are digital and global.

Getting rich trading gift cards

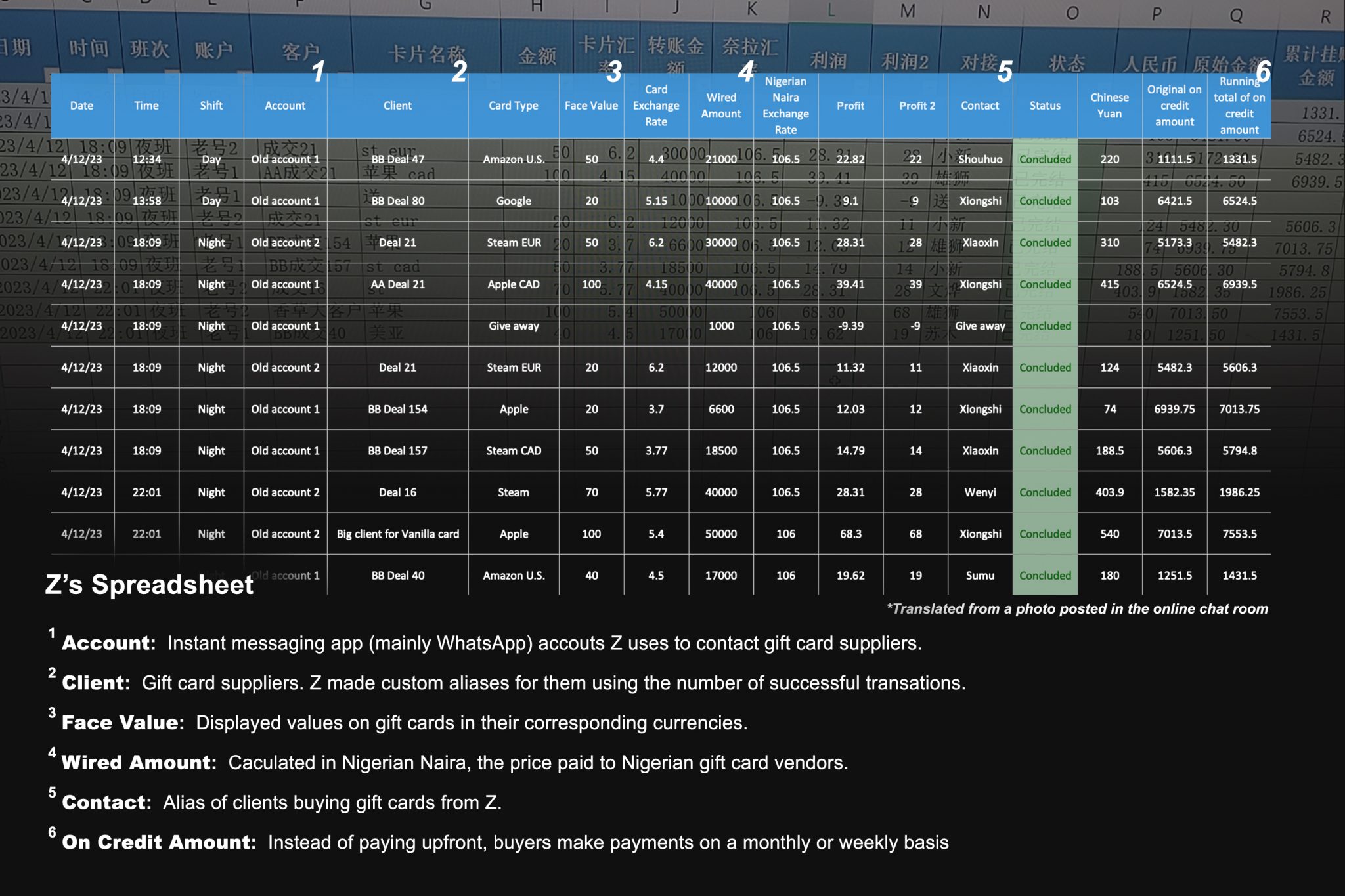

Gift card trading, in essence, is a simple “buy low, sell high” business. Brokers like Z source low-priced cards from gray markets like Paxful or directly from oversea sellers and sell them to Taobao vendors who then pass them on to consumers.

Finding stable suppliers for low-priced gift cards is the tricky part and requires, oddly enough, a commodity in short supply in the age of the scam: trust.

Attracting attention from those foreigners and convincing them to sell you cards is the hardest,” explained Z. “I’ve tried to pay to advertise myself but ended up with little effect. It’s all down to reaching out to each of them individually.”

Finding vendors is easy, according to Z. “Card vendors take everything,” said the dealer. “They like Steam gift cards the most, but they take every other card from iTunes, Google Play, eBay, anything.”

An article on “Zhihu,” a popular Chinese Q&A forum, called gift card trading “small gold mines” that generate “long-term, stable profits.”

While not breaking the law themselves, gift card brokers like Z are likely providing a money-laundering channel for gift card scammers to flip their ill-gotten cards into cash.

Understanding the life cycle of a gift card, especially how it gets converted to cash, matters since that’s the moment the card gains its value in the scammer economy. And not all of them end up in the hands of Chinese gamers. In fact, some illegally sourced gift cards make it back to the U.S. before they’re used.

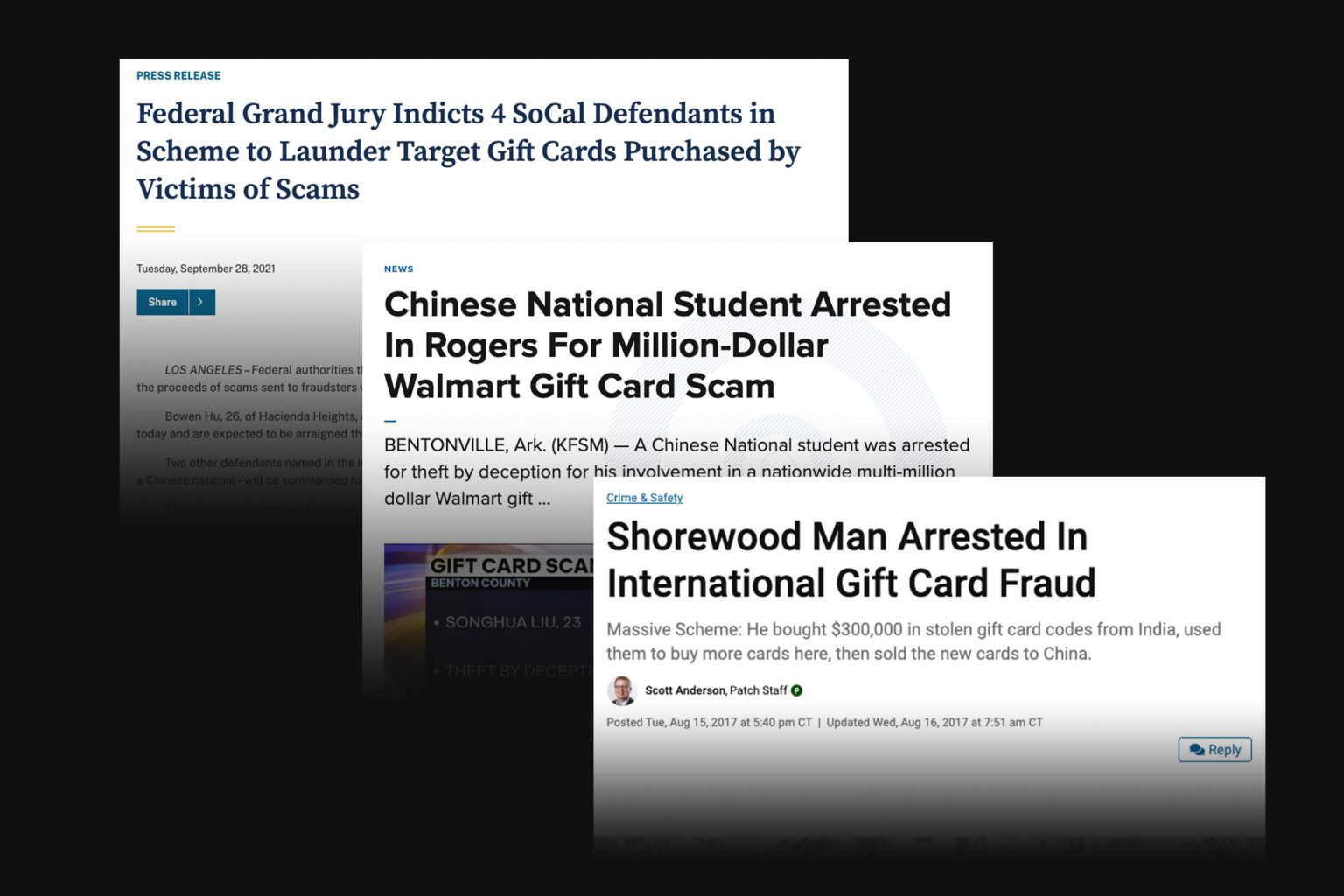

In 2021, a federal grand jury indicted four Californian-based individuals for their alleged attempt to use Target gift cards obtained via a transnational scam group for in-store purchases in stores across Los Angeles.

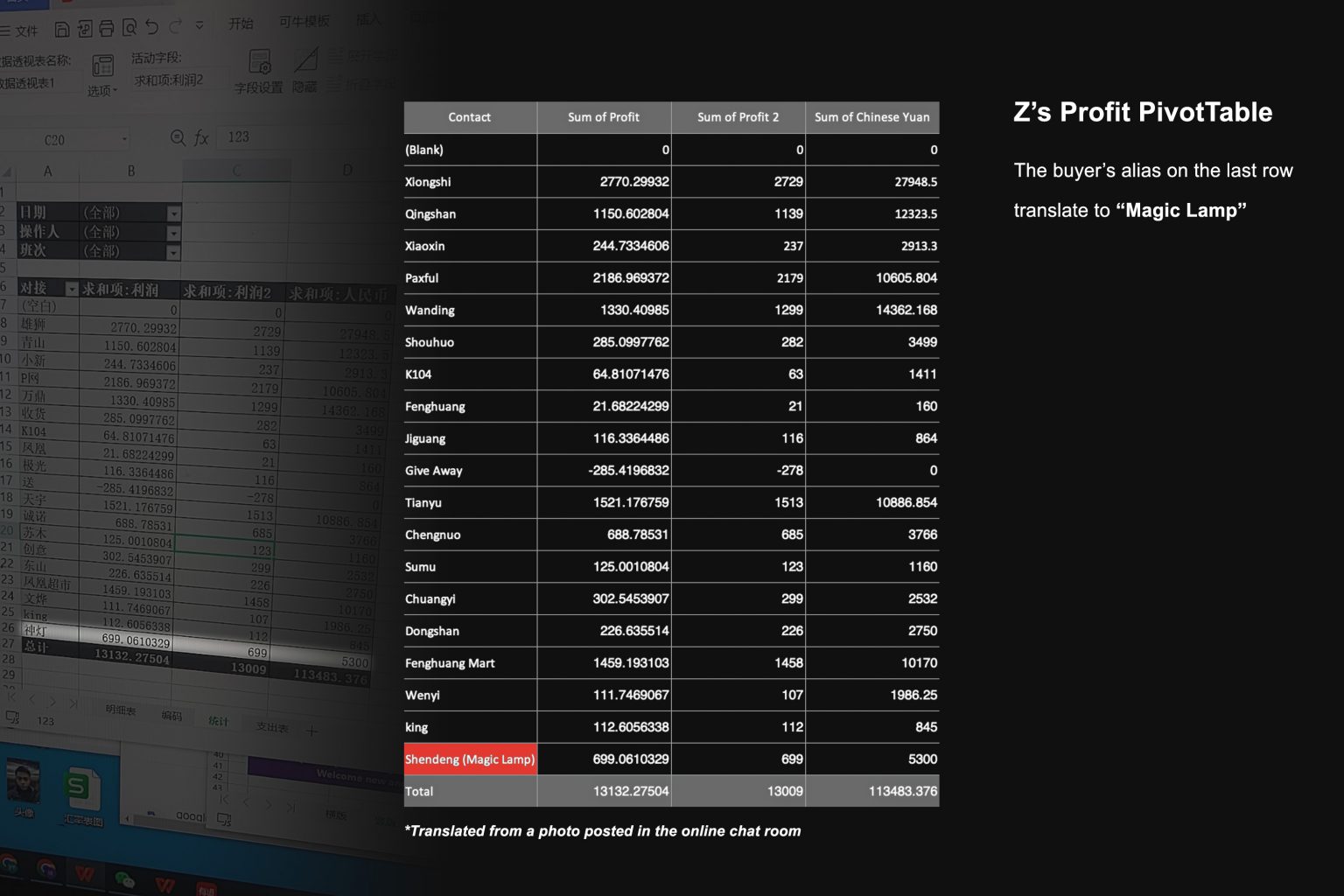

This group of four, consisting of three Chinese nationals and one U.S. citizen, allegedly bought over 5,000 gift cards from an online organization called “Magic Lamp,” which scammed gift cards by impersonating IRS officials. The indictment states that the accused helped Magic Lamp launder more than $2.5 million between June 2019 and November 2020.

The four were charged with “conspiracy to commit money laundering,” as they purchased ill-acquired gift cards from the scamming group and converted the stolen cards into goods and money.

This relatively recent federal indictment bears similarities with two earlier cases. In 2019, a Chinese national studying in the U.S. was arrested by the Benton County police for his use of Walmart gift cards acquired by scammers to purchase prepaid cash cards and other products across Arkansas, according to KFSM. In 2017 in Wisconsin, a doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee was arrested for using Target gift cards sourced from Indian personnel for purchasing Apple and Google gift cards that were then sold to buyers in China, Scott Anderson reported in Patch News.

All three cases involve Chinese nationals acquiring gift cards in large quantities from dubious sources and using them for commodities like gift cards for internet services, which can be converted into legal currencies.

Why China?

The Chinese internet is its own unique ecosphere. Since China erected the notorious “Great Firewall” in the early 2000s, the nation’s internet has gradually but effectively evicted all western service providers, which created space for indigenous tech firms to grow.

This “walled garden” has prompted some to seek what lies beyond its gates. VPN use is common for netizens of China to enjoy foreign entertainment. The worldwide “shopping craze” in the digital gaming sector also sees its ripple, or rather waves, in the Chinese market.

Yet, the country’s often conservative regime regards gaming as a youngster-corrupting “psychological opioid,” to quote Xinhua, a state-run media agency. Because of this, Chinese gamers need foreign gaming platforms to meet their entertainment needs.

This love of gaming by Chinese youth and the restrictive stance of the government creates the conditions for the booming gray market.

Although gift cards alone may not work for “ultramancliub” anymore, Taobao vendors are now offering in-app purchase proxy services: store staff can make purchases using the user’s game account, through a phone physically located in the U.S. to evade Google’s “geolocation lock.”

Purchase proxies on Taobao are thriving, with the platform’s stats for some vendors showing more than 100,000 monthly transactions. Steam, the hugely popular game distribution service from Valve, also has dollar-based account replenishment services on Taobao providing exchange rates far lower than the norm.

This market incentive created an almost infinite appetite from the gift card vendors, pushing card traders like Z’s profits to new levels. In a spreadsheet recording the recent transactions between Z and gift card vendors, the alias “神灯” appeared in the “client” field – “Magic Lamp” in Chinese. That’s the same group that sold 5,000 scammed gift cards to the alleged crime ring indicted in California.

Although Z’s connection to “Magic Lamp” is not conclusive based on the screenshot, he is open about his lack of ethical concerns regarding the origins of the cards he obtains. When asked if cards acquired through fraudulent means must be avoided, Z answered: “As long as it’s not an Amazon card, it should be fine.”

Amazon cards have protections that make them risker for scammers and platforms to trade in. In general, brokers prefer to use what they refer to as “white cards” obtained through legal sources. That makes it more likely the dealers and their customers will be able to redeem the card.

But these traders, like the rest of us, can never be certain of a card’s origin. So the traders factor some loss into their business models and try to use cards quickly before fraud protection can take effect.

“Some suppliers’ cards came from credit card fraud or calculated by some algorithms, which will be subjected to their value being canceled by the issuer,” the author of the Zhihu article warned. “Only buy them when you need them. Never stack them if you cannot immediately use them after the purchase.”

This resembles the behavior of some gift card sellers on Taobao. Many vendors noted the need to “contact the customer service agent in advance before purchasing” and ask the buyer to “use it immediately once purchased.”

According to another user in the chatroom, low-priced Steam cards almost entirely originate from an operation called “double transfer,” where scammers hack into people’s accounts and transfer the valuables out to a “zombie account” under the scammer’s control.

“You can almost guarantee 55% off when buying Steam balance from them,” said the user. “It’s all foreigners stealing and selling data to Chinese resellers.”

Professor Kristen Patel, a policy study professor at Syracuse University who spent the last 25 years identifying financial crimes for the federal government and some of the biggest international banks, says that what the user is describing is money laundering, plain and simple.

“The fraud happens between the victim and the scammer,” she said. “The scammer to the Chinese offloading is money laundering.”

The gift card trading operation is the “integration” part of the money laundering process, which, Patel explained, helps scammers “figure out how to get the money into the financial system” and “get that money back out.”

These cases can be hard to prosecute and require that the country where the scammer is based must act. For cases where the victim, the scammer, and the money launderers are each located in a different country, three jurisdictions must be involved.

“You’d need the Chinese government to go after the individuals who are the middlemen,” explained Patel. “That’s not an American thing because that’s where the money was going.”

Though nations do cooperate on cracking transnational financial crimes, getting results is often a lengthy process. “How countries implement those standards (established by Financial Action Task Force, FATF) are going to have variations,” Patel said. “That’s why it takes seven, eight years for a lot of money laundering cases.”

Why the gift card persists

Companies have been tightening their gift card policies, putting restrictions on redeeming locations, and prohibiting exchanges between card types. Yet the cards remain popular with both consumers and the companies issuing them.

Cash has long been considered the most liquid of assets as it is so easily used to purchase products without the need for a third party to enable it. But in a networked world, gift cards retain almost all characteristics of cash while also being digitally exchangeable.

And, like cash, gift cards are hard to track. After all, having the word “gift” in their name, the cards are designed to be easily transferable.

Companies are also reluctant to say ‘no’ to gift cards for the simple reason that they are profitable to issue, said Abhiruk Bhattacharyya, the author of a study for the crypto-exchange RocketFuel on how migrant workers use gift cards and cryptocurrencies to send money home.

“It’s almost like an interest-free loan for the company,” Bhattacharyya said. “You give me money even though I’m not really selling you anything.”

A lot of gift cards also end up unredeemed. A poll conducted last year by creditcards.com suggested 47% of U.S. adults claim to have unused gift card balances, averaging $175 per person, up from $116 in 2021.

“It’s almost like a win-win situation,” Bhattacharyya added. “For the company, issuing them, the person buying them, and ultimately, the person in the middle who … acts as a middleman.”

To Patel, the gift card is just another financial tool exploited by scammers. “Gift cards are the mechanism to move and store money. It’s not the scam itself,” Patel said. “The onus of responsibility is the individual who sends the money.”

While working at HSBC, Patel discussed the bank’s policies for preventing scams. “It’s really hard,” she recalled. “Is it the bank’s responsibility to reimburse that customer or not? Or is it the government’s responsibility to reimburse that customer when the customer actually was responsible for making that transfer?

“Is it the company’s fault? Who owns the gift cards?” she added. “So ultimately, the responsibility lies on the person who gave the money. … It’s ultimately about how do you stop people from falling for these scams.”