True crime or fake news?

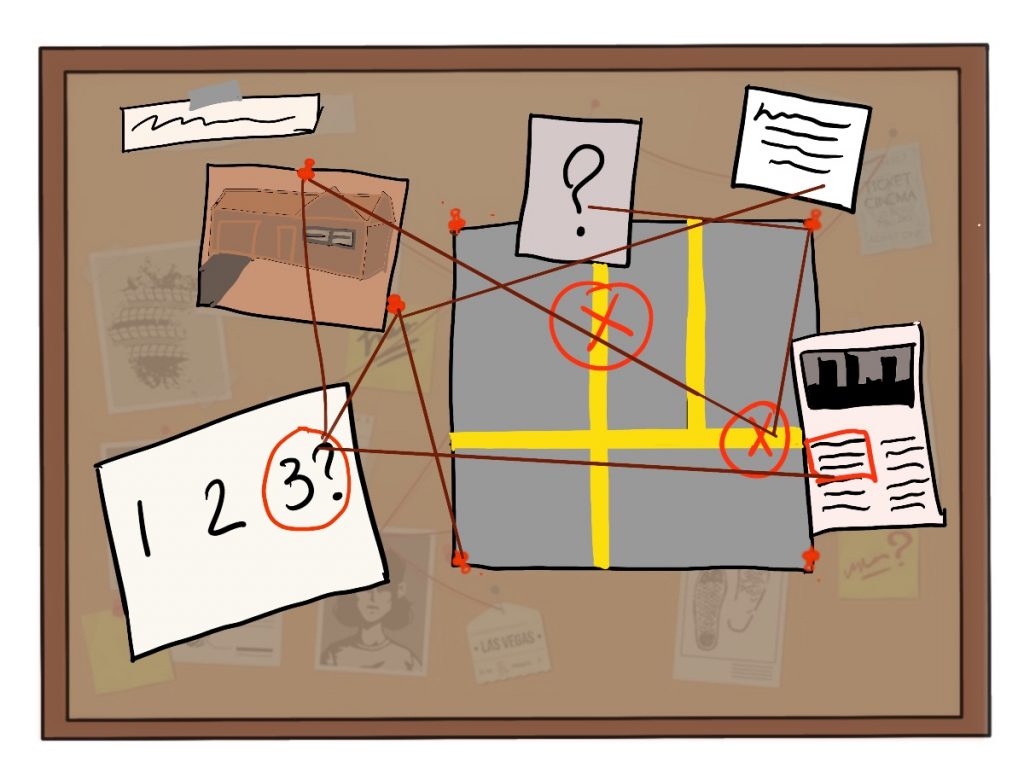

Despite its popularity, true crime media can sacrifice important nuances of crime for the sake of drama.

he title sequence begins with the unmistakable flashing of red and blue lights. The theme song “Bad Boys” plays in the background as different shots of police cars anticipate the episode. Then, a quick snippet of a forceful arrest. The suspect: a young Black man.

For the whole minute that the opening sequence plays, most of the short scenes exhibit a predominantly white police force arresting Black youth. Then, the sequence ends with the all-too-familiar declaration: “Cops is filmed on location as it happens.”

Cops is one in a plethora of true crime shows that claim to portray the realities of criminal activity. With its ever-growing popularity, true crime dominates various formats such as reality TV, docuseries, films, and podcasts. Even though the definition of true crime entails the evaluation of real crimes based on real people, experts say it is still common for certain media industry practices to taint these portrayals and skew reality.

True crime reality TV is an example of these industry practices, said Beth Adubato, an associate professor of criminal justice at Saint Peter’s University. The format of reality TV shows allows for a selective process that often alters or omits key details, she said.

“When it’s edited, it’s not the raw story,” Adubato said. “So obviously, they’re picking out certain stories that they want to include on the show right there. They’re also not really showing that the police know they’re on camera.”

Audiences can struggle to differentiate between fact and dramatization when presented with these types of shows, she said. Because of its reality-like, unscripted format, viewers interpret these shows as informational rather than framed for entertainment, Adubato said.

Other true crime formats, such as docuseries and films, utilize Hollywood strategies to portray a glamorized version of the realities of crime. Audiences criticized the recent Netflix show, Dahmer – Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story for romanticizing the serial killer’s crimes by choosing a conventionally attractive actor. Some viewers took to social media, claiming that casting actor Evan Peters as Dahmer rendered Dahmer a sex icon rather than a gruesome killer. At the same time, the show’s dramatized depiction of Dahmer’s cannibalism incited controversy for exploiting the grotesque realities of his crimes. But some audiences still interpret these kinds of shows solely as nonfiction.

A 2022 survey found that 45% of U.S. citizens somewhat agreed true crime provides a better understanding of the criminal justice system, demonstrating the educational value given to true crime entertainment.

At the same time, true crime formats allow for the withholding of information, painting misleading images of what criminal activity in America is like.

TV network A&E canceled reality show Live PD in 2020 for destroying unaired footage of a violent incident between police and a Black man who ultimately died in police custody. Bystander and security camera footage of George Floyd’s murder that same year sparked a global movement protesting racial injustice, demonstrating the possible power destroyed footage holds. In this way, show producers can manipulate the narrative about misconduct and injustice in law enforcement, evading accountability by omitting these clips from public view.

Media narratives also overrepresent certain racial groups as criminal perpetrators. News and entertainment media portrayals of criminality sustain the stereotype of the “Black criminal” — a narrative that can misinform audience perceptions of crime and justice, a 2004 study found. Young Black males accounted for a larger share of perceived offenders in violent crimes than their share of the U.S. population, according to a 2019 BJS survey. In 2020, Black juveniles made up only 32% of arrests in all offenses, while white juveniles comprised 64% of arrests in all offenses, according to data compiled by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Another misleading narrative arising from the true crime genre is that women are mostly victims of crime. The 2021 Criminal Victimization report found no statistical differences between the violent victimization of males and females. Yet, true crime formats portray women as victims more prominently than men and rarely as offenders. Women depicted as victims in true crime media often tend to be oversexualized and predominantly white.

The late PBS NewsHour anchor Gwen Ifill coined the term “Missing White Woman Syndrome” to describe this phenomenon. This syndrome suggests that mainstream media is fascinated with portraying cases of white female victims but still lacks attention for victims of color.

Frequent media victimization of women can also detract attention from the growing numbers of incarcerated women and the social programs necessary to deal with this issue, Adubato said.

“Women are the forgotten part of the criminal justice system,” Adubato said. “So if we continue to show fantasies, and people are getting their information from these fantasies, we are not showing the world what the world is really about.”

True crime media cultivates a space not just for misinformation, but also for disinformation to thrive. While disinformation involves deliberately spreading false information to tarnish the truth and cause harm, misinformation occurs regardless of intent.

Crime disinformation is especially harmful when it comes to the human aspects of crime. True crime disinformation about Maura Murray’s disappearance in 2004 generated false theories about the Murray family, said Julie Murray, whose sister Maura is still missing. One theory even went as far as falsely accusing Murray’s father of being an abuser who scared Maura into disappearing.

Murray said her family felt diminished by the negative media attention while still dealing with the grief of losing a family member.

“A lot of times in true crime, people approach it as if we’re characters in a story, and people lose sight of the humanity behind the actual humans left behind in the wake of these tragedies,” she said.

Murray, who now runs a TikTok page to reclaim the narrative about her sister’s disappearance, said true crime media has used strategies to distort the facts about the case while also tainting her sister’s and family’s name.

“Aside from my sister going missing, dealing with that aspect of true crime, that unethical side, where you take the most salacious, most sensationalized version of events, instead of taking the less sexy, the more fact-based version of events—has been the worst thing to happen in my family,” Murray said.

Kim Goldman, sister of Ron Goldman who was killed alongside Nicole Brown Simpson, O.J. Simpsons’ ex-wife, expressed a similar sentiment. Since her brother’s death, Goldman has become an advocate for victim’s rights and the media’s role in crime. The numerous theories that circulated about her brother were detrimental to Goldman’s family, she said.

“Hearing people talk negatively about him, obviously, is very upsetting,” Goldman said. “All of the rumors that he was a drug addict, that my brother was a drug dealer, that whole line of conspiracy theories are upsetting to me, because it’s so not who he was.”

Disinformation becomes memorialized online and forces victims to relive traumatic moments for years, she said.

“I am still dealing with this almost 30 years later, with people accusing me of accusing the wrong person and blaming the wrong person, and therefore, ‘I’m a bad human,’” Goldman said.

Consumers are able to turn off the media and continue with their days, but many victims don’t have that ability, she said. A single comment can change a victim’s whole day and their healing, she said.

“When there’s so much attention and media placed on family and their trauma, we don’t get to turn it off and walk away,” Goldman said.“We live with it, even if we didn’t want to worry about it that day.The disinformation being repeated over and over again with podcasts and books and movies, that moves further and further away from the actual evidence.”

Per a 2022 YouGov poll, one in three Americans consume true crime at least once a week. It is no surprise that the genre is one of the main perpetrators in spreading misinformation on crime. Regular news coverage can also spread misinformation, making it harder for audiences to isolate fake news from the reputable standing of news stations.

At the time of her sister’s disappearance, local news stations became the central source reporting on Maura’s case, Murray said. There was an incident where the police department found a letter in Maura’s dorm room and shared it with the local media as a “personal note” when it was just a printed email to her boyfriend, Murray said. Although the wording was later revised, the original framing of this information led to audiences believing Maura had left a suicide note, Murray said. The spread of this misleading piece of information hindered the case’s progress by removing public interest in its coverage, she said.

“Sometimes in smaller cases, like my sister’s, you’ve got one loud voice, and they become the authoritative source,” she said. “That’s how language is so important, especially early on.”

Although crime misinformation transpires throughout the media in varying ways, the result is always the same: a warped perception of how crime affects real people and real families. Kim Goldman offered some solace for those affected by misinformation in the media.

“Know your story, and understand what you want to share,” Goldman said. “Be patient with yourself as you go through the process, and give yourself the grace to heal.”