Reinventing ‘Officer Friendly’

How do SPD interns see Syracuse? The answer might depend on their required reading material.

Syracuse Police Department internship is placing Syracuse University students behind the public information desk to get to know the department and, along the way, try to repair community trust in Syracuse from the inside out.

The program is the product of a new internship partnership between SPD, the Onondaga County Sheriff’s and District Attorney’s Offices, SPD’s Police Athletic League and SU’s College of Arts and Sciences Advising Offices.

But SPD’s public safety communication internship is just one small part of SPD’s relationship with the community it polices — a part experts said may be misinformed by elements of this year’s required reading for SU-based interns.

Beyond the department’s public communications internship desk, experts and locals say there lies a whole world of nuanced, conflicting rhetoric on crime, public safety and the legacy of policing in America.

“Broadly speaking, (there are) a lot of long-held assumptions around policing people are starting to second guess or scrutinize,” said Libor Jany, a Los Angeles Times reporter who covers the Los Angeles Police Department. “It all depends on who you ask.”

From where SPD stands, interns may not fully get to see that nuanced world in the span of just 140 hours interning with the department.

Reading between the lines

For SPD interns from SU, an undisclosed SU alum has helped fund three $1,500 stipends for three students to complete the public safety communication internship, which is otherwise unpaid.

There’s just one catch: SU interns must read the 2015 nonfiction book “Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America.”

The book details the investigations of former Los Angeles Times reporter Jill Leovy as she shadows LA police detective John Skaggs on a murder investigation in the city’s South Central region. Through the lens of a 2007 murder case, the book explores the reasons behind LAPD’s low clearance rate for solving homicide cases in the South Central region.

Writing the book was a way for Leovy to highlight conversations about the future of policing and the disparate impacts of homicide on Black men in the U.S., she said.

“The missing piece, and the part that I think gets a lot less press, is the homicide ‘epidemic,’” Leovy said.

Homicide is the most precisely measured type of violent crime because it’s quantified by medical examiners’ reports, Leovy said, noting that Black men suffer disparate rates of homicide.

A 2021 study revealed that medical examiners did not accurately report more than half of fatal encounters with police between 1980 and 2018 as murders. Police violence, a leading cause of death for young men in the U.S., also disparately kills young Black men, a 2019 study found.

These findings don’t significantly change the overall picture of murder in America because police killings constitute a small fraction of homicides overall, said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist and former president of the American Society of Criminology.

Nationwide, U.S. homicide rates for all races sharply increased by nearly 30% in 2020 and continued rising at a slower pace in 2021, according to 2020 and 2021 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FBI, respectively.

Homicide rates fell again in 2022, but recent Gallup polls indicate that 56% of Americans, a record high, believe local crime is increasing. Another 78% of Americans believe crime is worsening across the U.S., according to the same poll.

Despite public perceptions about rampant crime across U.S. communities, violent crime rates overall have remained relatively static and low since 2010.

Homicide’s disparate victimization of Black men in the U.S. is a national emergency that some South Central residents told Leovy the media doesn’t seriously consider, Leovy said.

The book’s title and many of Leovy’s references to the region hail from a single word Skaggs said his colleague heard in passing from an alleged local gang member speaking about their neighborhood: “ghettoside.”

“The term captured the situation nicely, mixing geography and status with the hustler’s poetic precision and perverse conceit,” Leovy wrote in her book. “It was both a place and a predicament and gave name to that otherworldly seclusion that all the violent black pockets of the county had in common (…) There was a sameness to these places, and the policing that went on in them.”

In sum, she called her book a “very damning critique of police.”

The term “ghettoside” or “ghetto” traces back to racist policies which forcibly concentrated marginalized communities, including Black communities in the U.S., into neighborhoods with exit barriers and limited resources according to Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

While some scholars, including Rothstein, have argued in favor of keeping the phrase to study and describe neighborhoods like this, others have discarded it entirely for its inherent racism.

Leovy’s book also frequently references “Black-on-Black” violence as a key term at the epicenter of rising U.S. homicide rates which disproportionately impact Black men in America.

“It really was a different world then, and this sort of banning of terms had not gotten the engine that it has at the moment,” Leovy said of her decision to reference “Black-on-Black crime” in the book when she wrote it nearly 10 years ago. “I don’t mind that term, myself. And the people who I covered, who were Black, used it very often, very frequently, and we used it without intent except to draw attention to what they were concerned with.”

Historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad disagrees.

There is no way to use the phrase “Black-on-Black” violence in good faith because of the phrase’s racist origins, said Muhammad, a Harvard professor of history, race and public policy.

“‘Black-on-Black’ has become a trope to justify the assumption that Black people are exceptional in their violence, and that the sources of their violence are pathological, and that the problem of the high rates of violence within Black communities and among Black men is mostly a problem that Black people have to fix themselves,” he said.

The phrase also makes no sense since most homicides happen within groups, and all communities, not just Black communities, commit violence internally, he said.

Leovy’s book acknowledges homicide as an intimate crime, alongside recognition that white supremacy in the American legal system has, from the start, effectively created a criminal justice system that offers Black people little to no protection under the law.

“It might not seem self-evident that the impunity for white violence against blacks would engender black-on-black murder,” Leovy wrote. “But when people are stripped of legal protection and placed in desperate straits, they are more, not less, likely to turn on each other.”

The best way to hold space for crime’s disparate impacts on Black people is to simply describe the problem as is, without using the phrase “Black-on-Black,” Muhammad said.

“There’s no cultural or scientific value in the term,” he said. “The idea that you can only dramatize this by using the trope of ‘Black-on-Black’ crime or ‘Black-on-Black’ violence is just lazy.”

Calling attention to crime’s disparate impacts on Black men was important to Leovy and a decision she stands by as a journalist, she said.

Ignoring uncomfortable truths only generates harm, rather than avoiding it, she said.

“I can’t control how people interpret my book,” Leovy said. “But what I can try to do is get in very close, document as accurately as possible, and certainly, to show the reality in the world without an agenda.”

To junior Brooke Papillion, SPD officers have mostly existed in the background throughout her time at SU.

Papillion prefers SPD’s invisibility to her encounters with LAPD at home in South Central LA, which she’s never heard anyone refer to as “ghettoside,” she said. But the bleakness of Leovy’s book otherwise mostly holds true in Papillion’s experience of living in South Central her whole life, she said.

“I think my relationship and history with LAPD has affected how I view most police departments in America,” Papillion said. “I have low expectations anything’s actually going to get done or justice is actually going to be served.”

the internship

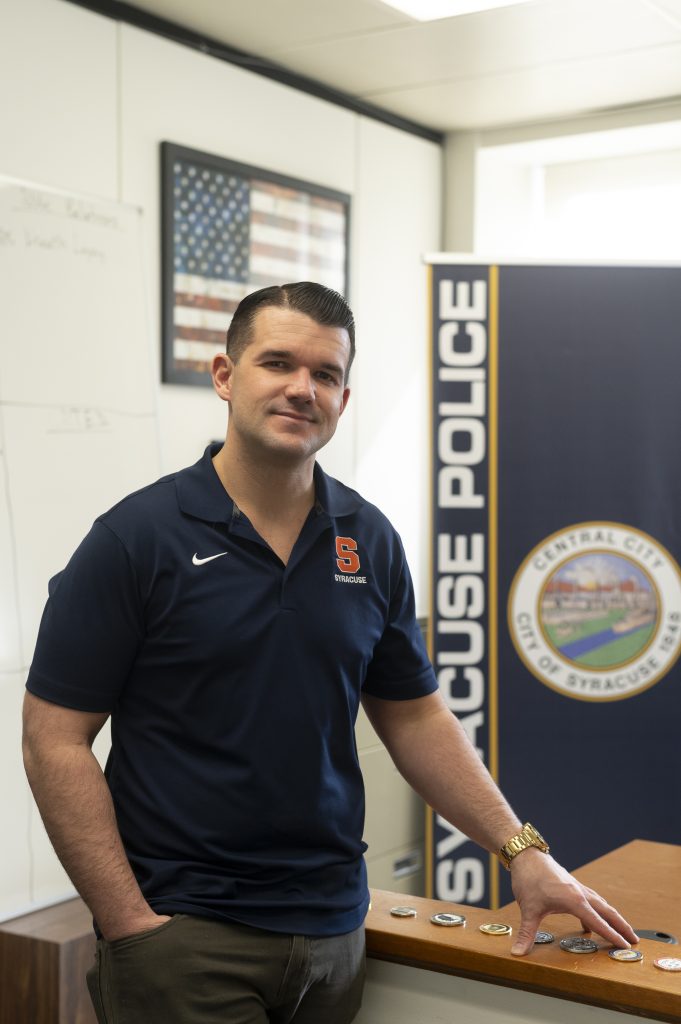

Lieutenant Matthew Malinowski has not read “Ghettoside.”

“It’s a very busy city,” said Malinowski, SPD’s public information officer who coordinates the public safety communication internship. “It’s hard for me to find time to read at the moment.”

All four of Malinowski’s interns have been SU students since the program’s start in 2021, Malinowski said.

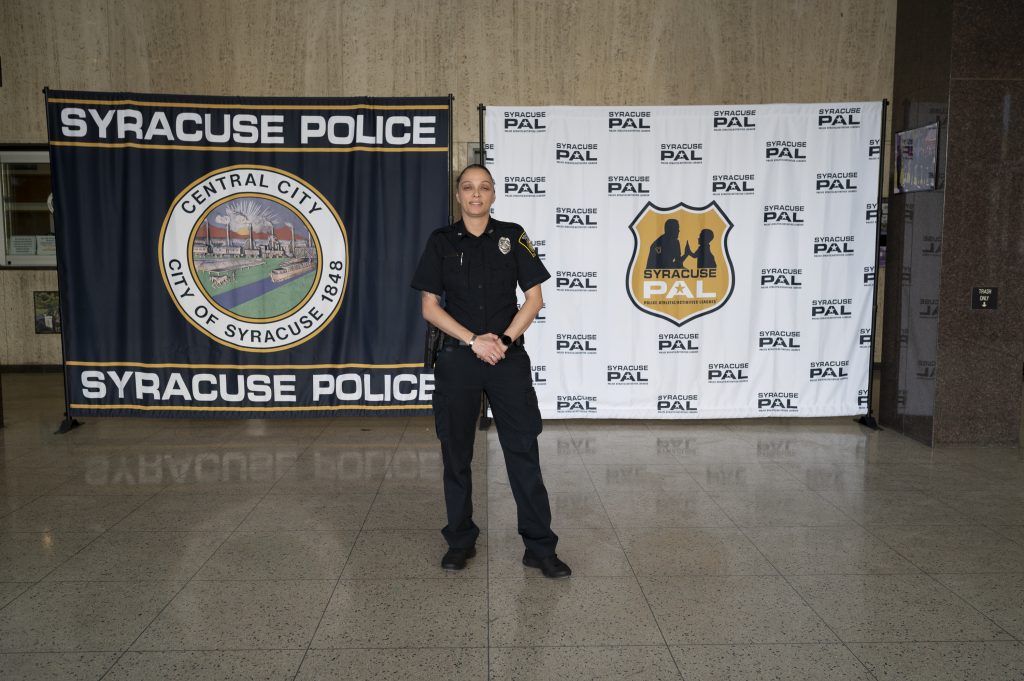

Although Syracuse residents may have negative views of SPD, interning with the department isn’t about persuading interns or the city at large to see SPD more favorably, said Officer Marlena Jackson of SPD’s community relations section.

The internship is about widening individual perspectives and serving the community, said Jackson, who supervises other interns in separate SPD internship programs.

“They don’t have to necessarily be in love with the police,” Malinowski said of incoming interns.

“It helps if you’re interested in law enforcement, but it’s more about representing an organization and the important work that public relations does, especially with the community,” Malinowski said, adding that through his work he’s aware that SPD has the least connection with Syracuse’s African American community. “In urban policing, we tend to have challenges with certain parts of our community, so that job is just that much more important.”

Former SPD intern Skylar Swart could easily see herself in a policing career.

“I’ve always liked the role of being a cop,” said Swart, a senior at SU. “Obviously, there’s some police officers that are corrupt (…) but I think as a whole they do more good for society than they do bad.”

Swart, who is majoring in political science and newspaper and online journalism, interned with SPD in fall of 2021. After graduation, Swart is considering law school, she said.

Swart initially missed the deadline to apply for the internship, but upon reaching out quickly found that SU Career Services had received no applications for the year. The internship did not require reading material at the time.

Swart interviewed immediately and began interning with SPD right away.

Swart was excited about the internship as a chance to see Syracuse up close like never before, she said.

“Obviously, the Syracuse community is different than other kinds of communities because they’re more underprivileged,” she said. “There’s more crime in the community. So I definitely saw a different side of things.”

Syracuse experiences higher levels of crime than other places in Onondaga County, but it’s hard to definitively say how Syracuse compares to other cities in the U.S., Malinowski said.

The idea that there is more crime in Syracuse than other spaces in Onondaga County is widespread among SPD officers, he said. SPD references comparative crime statistics of the city’s neighborhood divisions to inform policing strategies, he said.

Swart spent much of her SPD internship in the police station responding to journalists’ media requests, creating social media graphics and organizing police-community engagement events.

Apart from the occasional complaint that SPD had not responded to an incident quickly enough, Swart didn’t see negative encounters take place between Syracuse residents and SPD, she said.

As part of her internship, Swart participated in a nighttime ride-along with a female officer in a patrol unit.

Swart saw the officer respond to an argument between a mother and daughter, but there was not much the officer could do since neither person wanted to press charges, she said.

In another response scene, Swart followed the officer into a hospital where a babysitter had injured a baby in water that was too hot to bathe in.

“We ended up at the hospital a lot because there were so many stabbings and shootings,” Swart said, adding that the experience was scary but eye-opening to her.

Swart would recommend the internship to other students too, even if they were more skeptical of policing, she said.

“I think if I were somebody who had (negative perceptions of the police), it would have been pretty eye-opening because you see how dangerous their job is and how unpredictable it is,” she said.

SU Career Services will not provide SPD with intern candidates this year due to a lack of applications for the three open intern positions, said Jessica Smith, Director of Communications and Media Relations for Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs Office of the Dean.

Only two SU students applied for the internship this year, Smith said.

beyond the desk

In 2021, just four days after SPD officers stopped an 8-year-old boy who was accused of stealing a bag of Doritos, SPD officials revealed a yet-unknown, intimate detail of the encounter: the boy was no stranger to SPD.

Police said the commanding officer of his North Side neighborhood had visited the boy’s home a month before to gift commemorative police badges to him and his brothers, according to Syracuse.com. Mayor Ben Walsh also said he knew the boy and his siblings from playing with them in the Syracuse Police Athletic League.

The situation was not unlike many other children’s encounters with SPD, said Ranette Releford, administrator for the Syracuse Citizen Review Board.

The “potato chip case” was just another strand in the story of many residents’ strained relationship with the department starting from a young age, she said.

“I don’t believe it’s an isolated incident,” Releford said. “This one just got caught on camera.”

Releford’s days as Citizen Review Board administrator are filled with investigating residents’ complaints against SPD officers. CRB complaints run the gamut from complaints about slow police response times to complaints about excessive force, officer demeanor, racial profiling and harassment, Releford said.

Releford takes the CRB’s work in police accountability seriously, though it’s a job she believes is heavily burdened by underfunding and not enough staff — the same obstacles Jackson said get in the way of her community relations work with SPD.

Malinowski’s work as public information officer often converges and blends with the work of SPD’s public relations and community relations sections, he said.

With a total budget of more than $55 million, SPD dedicates $225,000 to its community relations team of four staff, which includes two civilian staff members, Malinowski said. The city will give more positions on the team to civilians in order to “free more police officers on the streets in patrol and to help reduce crime,” according to the city’s 2022-23 fiscal year budget report.

The CRB, staffed exclusively by Syracuse civilians, currently has four paid staff positions with a 2023 total budget of $264,938. The city approved adding Anthony Heard’s role as community engagement specialist to the CRB’s budget just last year.

Heard said he feels a deep sense of responsibility in his new role. As a community engagement specialist, Heard spends his time planning CRB community events in spaces like the Boys and Girls Club to teach kids about topics like levels of contact with police interactions and how to act more cautiously around officers to avoid confusion or escalating conflict, he said.

“Depending on the resource officer that they are involved with, or they have at their school, regular children’s behavior can turn into things that they didn’t anticipate,” Releford said. “That’s the parts that concern us the most.”

To create a police department more representative of Syracuse, the community needs to rebuild its trust in the police, Releford and Heard said.

That change starts with young people in Syracuse, Releford said.

“It takes more than the police,” Heard said. “It takes a community. Just like a family member will say ‘It takes a village to raise a child,’ it’s the same within the community. It doesn’t just take one person, one avenue, to create something great.”

Heard and Releford are not alone in their faith in community-driven change.

A 2022 study by the National Academies Committee on Law and Justice confirmed that measurably reducing inequalities in the criminal justice system could depend on community-based organizations more largely than government actors.

The study draws on 2017 research which shows “community-based organizations that fought against rising crime in the 1990s were responsible for a significant portion of the crime drop in subsequent years,” using tactics like creating youth programs, building community centers and cleaning neighborhood streets.

Instead of giving untrained police officers the authority to be everywhere at all times for children, shrinking the criminal justice system’s footprint is the definitive next step, said Muhammad, who produced the study as part of a panel of federal judges, sociologists, law professors and a former police chief.

Police social events like coffee meet-and-greets won’t produce meaningful levels of trust and change, Muhammad said.

“The same cop who is doing a Saturday program to deliver coffee to some kid may be the same kid who pulls over that kid’s parent or older sibling,” he said. “There’s no relationship between those two activities. None whatsoever.”

At the end of the day, police officers aren’t trained to mentor children, coach basketball games or build meaningful community relationships, Muhammad said.

“There’s no relationship between ‘Officer Friendly,’ who is within the constraints of a specific program on a Saturday afternoon with these joyous, delightful little kids, and how that same cop behaves when he or she shows up on a call for service at someone’s house in the projects,” he said.

different views from the hill

Thousands of miles away from her home in South Central, Papillion said she felt the same frustration with police returning to her doorstep in Syracuse in November 2022.

Papillion’s friend Rufus Sivaroshan, who uses they and them pronouns, told her they were racially profiled by two SPD officers while walking up to the steps of their off-campus apartment on Livingston Avenue in Syracuse.

SU junior Sivaroshan felt nothing out of the ordinary as they biked along Stratford Street on Nov. 17, their shoulder turned against the cold and a barely visible police car parked nearby in the dark.

They had pulled up to their apartment on the corner of Livingston and Stratford, bike in tow behind them, when Sivaroshan said two SPD officers suddenly appeared behind them with flashlights, demanding to see their ID.

Sivaroshan had not seen them coming.

“(The officers) asked for my ID and they said ‘You looked very suspicious. You were wearing a black jacket and you were zooming so fast,’” Sivaroshan said.

To hear that the two white, armed female SPD officers suspected Sivaroshan to be a burglar was at once devastating and terrifying, they said.

Sivaroshan called SPD to file a complaint over the phone immediately after the incident took place, but their faith in SPD is unmistakably shaken now, they said.

“After a search of records in the Syracuse Police Department, no reports were found,” a representative for the city of Syracuse said in response to a Freedom of Information Act records request for Sivaroshan’s complaint. “The requested incident was closed without a report being filed.”

Sivaroshan has never heard of SPD’s community engagement initiatives, but beyond charity events, real change is the only thing that could fully remedy the situation for them, they said.

“I just always fear that something’s bad,” they said. “Like, just everything that I’ve seen? I don’t want to be another case.”

Editor’s note: Skylar Swart, a source in this story, is also a member of the Infodemic project team.