Museum-goers encouraged to question the truth at MoMA’s “To look without fear”

Wolfgang Tillmans has included a table-based “Truth Study Center” at the core of most of his major exhibitions since 2005.

EW YORK CITY – Arranged and installed through a method that Wolfgang Tillmans has described as a “visual democracy,” photographic prints hang sprawled on the high-walled Museum of Modern Art space with white and silver clips, tape and thin white frames. As packs of viewers rapidly maneuver through the German artist’s 11-room career retrospective, “To look without fear,” they are encouraged to reflect on his vision of today’s humanity, captured by his camera lens.

Fans of Frank Ocean’s album “Blonde” pose for a photo op in front of the album’s cover art — Tillmans’ “Frank, in the shower” — and then continue their rapid pace through the crowded retrospective.

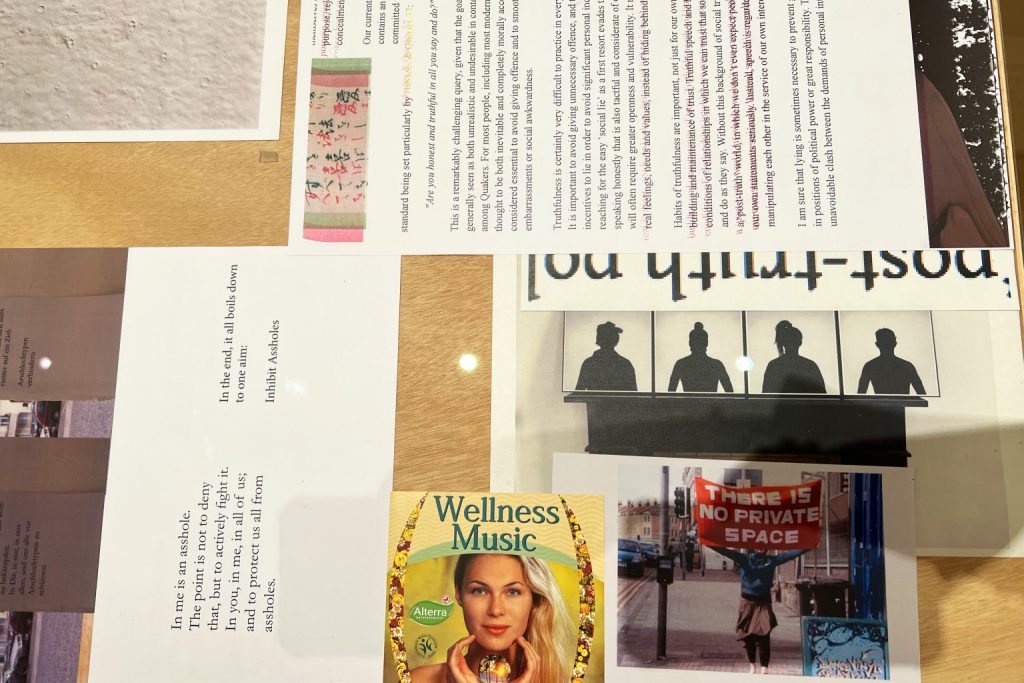

But the pace slows down dramatically as they reach the exhibition’s core, the “Truth Study Center” installation. The crowd weaves through the wooden tables unrushed, aware on some level that viewing an artist’s oeuvre via smartphone is never sufficient. Instead, with furrowed eyebrows, they examine each piece of Tillmans’s unconventional and informationally dense installation in silence.

“There’s just this mysterious aspect about it,” said ARTnews editor Alex Greenberger. “It’s definitely the interruption within a gallery.”

“Truth Study Center,” often used as the centerpiece of Tillmans’s solo exhibitions, invites viewers to reflect on certain claims of truth that have overwhelmed the media and polarized humankind. Instead of directly denouncing disinformation and highlighting factual truths, he fuses collected materials — newspaper clippings, photos and much more — into tabletop displays that let the viewers decide: Is what I believe actually the truth, or is it disinformation?

“I do think there are certain truths that are not negotiable, that some events and attitudes are wrong, and I am straightforward about that in the work, which I think is precisely what makes it interesting,” Tillmans said in a 2011 interview in conjunction with a New Museum exhibition. “It takes a moral stand on the one hand, but on the other is always aware of its absurdity and of its extreme limitations.”

Underneath the glass tabletop of each unvarnished wood table are clippings, printed articles, photos and even found materials like a paper doily or a cherry-patterned aluminum yogurt lid that Tillmans strategically places and overlaps. Some printed items are mangled by design, with warped drop caps and streaks of cyan, magenta and yellow that artistically smudge or permeate photocopies. Greenberger emphasized that it seems as if Tillmans distorts certain materials to prevent viewers from reading entire texts.

“Part of his work attempts to create this kind of chaos,” Greenberger said. “He’s giving you more information than you could possibly ever consume. And I think he intends to do that very much.”

Before starting this ongoing project, Tillmans — who calls himself a “newspaper junkie”— used newspapers as his medium in the 1999 series “Soldiers,” a critical study of ways the media portrayed soldiers in 1990s photographs. Tillmans has said the idea to lay out materials on a flat surface originated in 1995 when he displayed his magazine-published photos inside horizontal cabinets at Portikus in Frankfurt, Germany. Tillmans said he now feels that tables are the epicenter of his work as an artist.

“A table provides a space for a loose arrangement, where things are laid out in a certain way, but can be easily rearranged,” Tillmans said in 2011. “On a wall you have to pin or tape the stuff, but a table is more fluid. There is clarity and complete contingency at the same time.”

In the years after the 9/11 attacks, Tillmans said he began to feel that, as a means of justifying violence and war, the news transformed into a daily dispatch of truth claims.

“I realized that all the problems that the world faces right now arise from men claiming to possess absolute truths,” Tillmans said.

Since he exhibited the original, 24-table version of “Truth Study Center” in 2005 at Maureen Paley gallery in London, Tillmans has made nearly 300 tables, said Shahin Zarinbal, one of his studio assistants.

The 18 tables at MoMA examine themes like the 2016 election, the death penalty, AIDS denial, the search for other habitable planets, attitudes toward food, violence and video games — topics that Tillmans realizes are centered around extreme, opposing truths.

“Truth Study Center” has never been a fixed installation. While he does maintain certain subject groupings that he finds effective, Tillmans tailors it to each audience. He often updates tables into reconceptualized versions.

“There’s this openness to it,” said Greenberger of ARTnews. “I think he really does want to respond to the ways that he, and the world around him, and the people around him, change.”

Zarinbal said Tillmans created new, site-specific versions of “Truth Study Center” for each destination of “Fragile,” an exhibition that toured eight different African cities beginning in 2018.

Layered on top of a table at the far end of MoMA’s “Truth Study Center,” several slips of white paper toy with the objectivity of time with statements like “Now 1993 is as long ago as the Civil Rights Act was in 1993.” Underneath, Tillmans layers a few New York Times articles that discuss the Republican Party’s efforts to suppress the rights of historically marginalized people and disseminate election-related disinformation.

At a different table, newspaper clippings and photos related to events in Iraq are grouped with a slip of paper that reads, “The beginning of the Iraq War in 2003 is now 19 years ago. In 19 years it will be the year 2041.”

These tables, which he calls “Time Mirrored,” can be found scattered throughout the MoMA “Truth Study Center.”

“They confront us with how differently we perceive periods of the same time length, depending on where we stand,” Zarinbal said.

Greenberger said he likens “Truth Study Center ” to being immersed in an intense thread of Tillmans’s Google searches. The artist groups the objects and documents in a way that isn’t immediately obvious for the viewer, who must try to guess the reasoning he used for each table.

“I think these kinds of installations have that feel to me, where I want to reconstruct that logic, but can’t totally do it,” Greenberger said. “And I think that is actually a pro to them, not a con.”

Tillmans seems to be presenting his work as a form of journalism, Greenberger said, one created through synthesis rather than through reporting and writing. The installation represents Tillmans’s own informational study and suggests that everyone’s own personal archive will also develop differently. He isn’t claiming that “Truth Study Center” is the absolute method of seeking truth — but perhaps it could be.