Review: Third day of horror movie madness with Nightstream

Review: 3rd day of screams for Nightstream

With one more day of the Nightstream Film Festival to go, fans of the horror genre can still get their spooky film fix. The festival kicked off on Thursday, pleased our NewsHouse reviewers on Friday and brought more screams last night. With films like AV: The Hunt, Darkness, Bleed With Me, Rose Plays Julie and The Obituary of Tunde Johnson, Nightstream’s Saturday night movies covered many different bases.

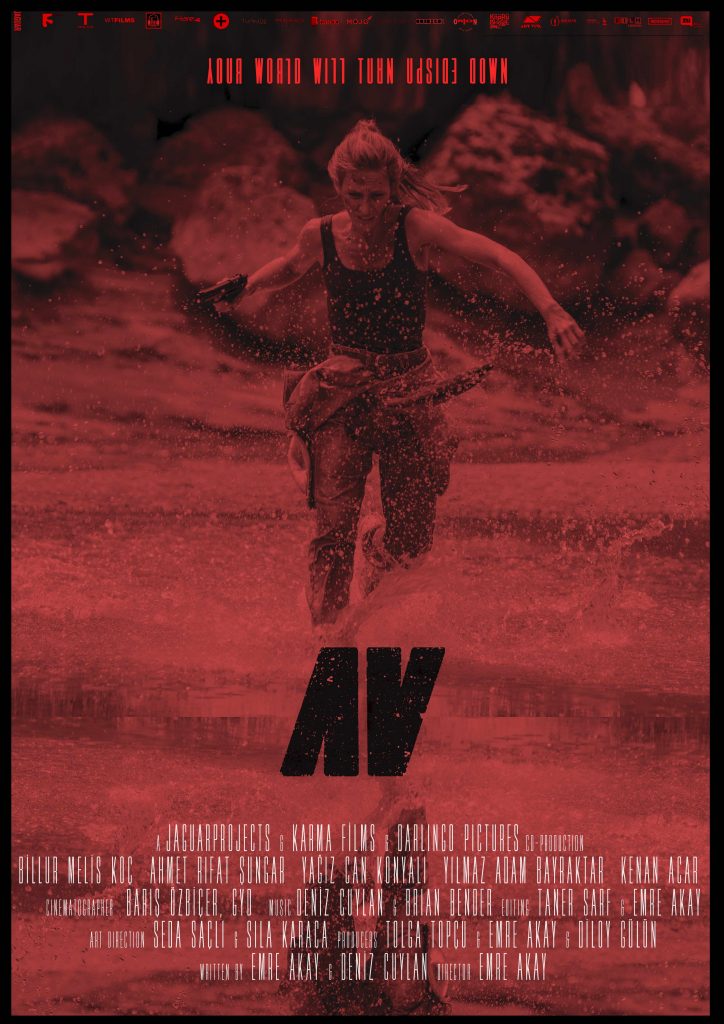

AV: The Hunt

AV: The Hunt is a Turkish survival thriller directed by Emre Akay. Leaving no time for exposition or explanation, the film opens with Ayse (Billur Melis Koç) and her lover in his apartment. Suddenly there is a banging on the door, and in walks Sedat (Ahmet Rifat Sungar). He quickly kills Ayse’s lover. Ayse jumps from the balcony to the street and begins to run.

The audience is left with more questions than it should be for this film’s first 10 minutes.

The audience later finds out that Sedat is her husband and that she has been in the process of trying to leave him, albeit unsuccessfully. The remainder of the film features Ayse attempting to make her way to Instanbul while Sedat and his cronies hunt her down.

The underlying thread of the patriarchal society Ayse is running from is exceptionally prominent. Her female friend and sister pity her situation but can do nothing to help lest they put themselves at risk. The males in her life, including her brother Ahmet (Adam Bay), treat her as chattel to be wrangled and returned to her rightful owner.

The Turkish wilderness creates a stunning backdrop for the beautifully crafted scenes. Every carefully chosen shot of the 86 minute film makes the audience feel as if they are both hunters and prey.

Although there are supposedly wild boar in the forest the majority of the film takes place in, the pig noises in the score do not add to the ambiance created. At certain points, they come off as comical and detract from the terrifying reality that AV: The Hunt demonstrates.

AV: The Hunt is a substantial addition to the survival thriller genre, perhaps made all the more terrifying by the patriarchal values it demonstrates. The film ends, leaving the audience with some significant questions and no answers, possibly setting up a sequel but more likely to continue the terror after the credits roll.

– Mackenzie Snell

The Obituary of Tunde Johnson

Tunde Johnson wakes up hyperventilating in his bed five times. Each morning is preceded by an unwarranted encounter with police and his death at their hands. He is living in a time loop and reliving his demise.

Ali Laroi’s The Obituary of Tunde Johnson follows Tunde Johnson (Steven Silver) — a lovesick, gay, Black 18-year-old as he relives coming out to his parents and getting killed by LAPD over and over again.

Despite his impending demise, there is an element of drama via a love triangle that involves him, Marley (Nicola Peltz), his prissy childhood best friend, and Soren (Spencer Neville), his secret lover. Tunde’s relationship with the latter — unbeknownst to Marley who is seemingly f–k buddies with Soren and wants to define the relationship — is implied in the opening scene, as he is editing a video reel of Soren, whose dreamy facial features resemble that of James Dean.

Interestingly enough, each day, Tunde is too preoccupied with making amends in his love life to even try to prevent the loss of his own. However, adding this teenage drama was a good move by Laroi because the film probably would have been boring otherwise considering we become privy to the time loop effect 32-minutes in. Tunde is still a teenager and Laroi reminds us of this by including school and love scenes. Society often ages Black children, robbing them of their innocence because of stereotypes. Getting a glimpse of Tunde’s bouts with his parents, love and therapy distracted from the infuriating moments to say the least.

While there are no traditional elements of horror like blood, gore and jump scares, The Obituary of Tunde Johnson is a horror film in its own right. The last encounter a Black person in this country wants to have is one that involves police. They have shown us time and time again their blatant disregard for Black lives through racial profiling and killing unarmed, innocent Black people all under the guise of “enforcing the law.” Tunde’s encounters with the police vary by time of day, setting and cause of death, but this doesn’t even matter because the outcomes are all the same.

Tunde Johnson just wants to be heard and seen, both as a Black boy and as a gay boy. He no longer wants to hide his relationship with Soren, and he doesn’t want to be dehumanized because of his skin color. In an emotional scene with his therapist, he says: “I’m Black and gay. And even those two hate each other. Which means, in the eyes of humanity, I’m like two degrees off human.”

The cyclical, albeit differing situations make for a more or less unpredictable and emotional sequence of events for Tunde Johnson. The use of the time loop was executed well, as this film raises the question of the extent to which we have control over our individual lives.

– Cydney Lee

Bleed With Me

Bleed With Me, a thriller that takes its audience on an unsettling journey from the beginning, proves to become more and more complicated with each passing minute. From the beginning scene, there is a sense of separation between couple Emily (Lauren Beatty) and Brendan (Aris Tyros), and Emily’s friend Rowan (Lee Marshall) whom they have invited along for a short getaway to Emily’s family’s cabin.

The dynamic between the three continues to be awkward, as the couple take turns criticizing and defending Rowan in different scenarios. It’s unclear at the beginning what this storyline could possibly be about, but as Rowan begins to have unsettling nightmares and what seems to be sleep paralysis, it becomes clear that there’s an obvious connection to her friend Emily who tries to convince her that she’s simply not feeling well and should rest.

The film keeps its audience engaged by delving in and out of Rowan’s continuous cycle of nightmares and confusion, and it feels as if there’s going to be a massive unexpected twist at the end to finally offer a clear answer to what’s been going on. There’s an uneasy but strong buildup throughout the film as certain pieces start connecting with one another, which can be traced back to the first night the three spend in the cabin when Rowan accidentally cuts her finger with a knife and Emily licks the blood off.

The ending provides little satisfaction in the way typical horror movies have a grand ending, and in this case, it requires the audience to piece the clues together themselves, which isn’t easy to do after a first viewing. It’s nearly impossible not to sympathize with Rowan throughout the film, but the attempted subtlety with no surprising climax didn’t work with the story line, and it would have benefitted from an ending that was more clear.

– Natasha Breu

Rose Plays Julie and Darkness

We often think of horror as those things that go bump in the night – the malevolent spirit in the abandoned old house, the knife wielding lunatic at the dark dead end – but what about the terrors in our own home? The tiny, frightening truths revealed by those closest to us can be, in the hands of the right storyteller, just as scary – and as deadly – as those chainsaw chasers and satan worshippers.

Familial horror, the evil lurking within our own ranks, is the territory explored by two of the best movies I screened at this year’s Nightstream Festival – the Irish psychological shocker Rose Plays Julie and the quiet, Italian chiller Darkness. Both films situate themselves in a slightly off color reality and play out as twisted fairy tales filmed with the drama of dread.

“Who are you?” That question reverberates throughout Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor’s Rose Plays Julie, which places sense of identity as an existential prerequisite – when adopted college veterinary student Rose (Ann Skelly) seeks out her birth mother Ellen (Orla Brady), a famous actress living in London, she is looking for a connection to a life she never knew. In Dublin, she feels like an outsider; she sleepwalks through classes, unable to shake the feeling that she was meant to be someone else entirely – at first, Ellen doesn’t want anything to do with Rose, who was named Julie at birth, but eventually the two form a bond – mother and daughter reunited after years of separation.

Rose’s father is another story altogether – a famous archeologist named Peter (Aidan Gillen) who raped Ellen, he is married to another woman and doesn’t even know that Rose exists. From here, Molloy and Lawlor examine these relationships with a creepy, archetypal remove; Ellen is an actress, disguising herself and her pain through years of impersonating other people, while Peter digs up bones and preserves the past while neglecting the horrors of his own. And Rose, spending her days in school euthanizing dogs and butchering cows, is searching for her truth yet finds something far worse than the lie she was living – she’s the product of violence, as alien to the people who created her as she is to herself.

Lies permeate throughout Emanuela Rossi’s Darkness as well, which follows Stella (Denise Tantucci), a young woman living with her father (Valerio Binasco) and sisters on the outskirts of an Italian city. Stella’s father is a doomsdayer who uses apocalyptic dogma to control her and her sisters –– teenage Luce (Gaia Bocce), and the even younger, mute Aria (Olimpia Toasatto). Windows are boarded up, the front door is zoned off with plastic tarps, and the girls’ days are strictly regimented. Stella takes the brunt of abuse from her father in order to protect her siblings –– their mother, it is revealed, died some time before, and it is heavily implied that he has been sexually abusing Stella.

The darkness of the title is both literal and figurative – while the girls are told that the sun has undergone some massive explosion and now is deadly to anyone who steps out unprotected, they are also subjected to medieval religious indoctrination. Women are evil, their father tells them, and if they don’t follow his ways they’ll end up damned like their mother. And so Stella’s coming of age is also a quiet rebellion – when her father goes missing she must venture out and find food for her sisters. The world is far more intact than the she suspects, and scenes of her at grocery stores or interacting with kids her own age play out with the same optimistic relief as the equivalent moments in Lenny Abrahamson’s Room – which makes the film’s shift back into the darkly traumatic finale all the more powerful.

Both of these films benefit greatly from the lead performances – in Rose Plays Julie, Skelly guides us through the film with an unnerving calm (the most taut sequence happens during a seemingly normal real estate open house), while Tantucci carries Darkness with a sympathetic sadness. It’s a wonder, too, that both films examine isolation as they do, in physical and metaphoric terms – perfect fodder for our closed-off world and digital film festivals. And fatherhood, as an instrument of creation as well as destruction, figures heavily in these stories –– though these are foreign films, they speak to a dynamic currently at play in our American lives. The men at the head of our societal family are as confusing as the fathers in these horror movies. We desire their presence, but proximity is dangerous – we want the truth, but at what cost? Violence begets violence, these films warn; but sometimes it’s the only way.

– Matthew Nerber