Inside the ‘Fyre’ flop: SU alum witnesses fiasco firsthand

SU alum witnesses 'Fyre' fiasco

Syracuse University alum and photographer Drew Osumi shot staple SU events like Juice Jam and Mayfest, but none of those prepared him mentally or emotionally for shooting the Fyre Festival.

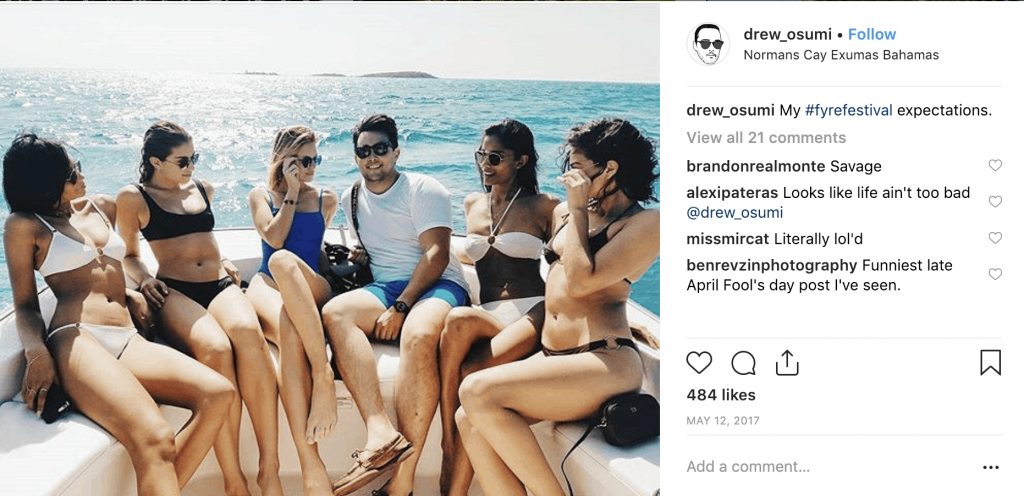

Osumi, 25, helped shoot the event’s promo as a “behind-the-scenes-slash-creative” photographer, at the infamous influencer-jammed promotional shoots that enticed about 5,000 people to spend between $900 to $250,000 on VIP packages and tickets for what was expected to be an elite, two-weekend music festival in April and May of 2017.

The whole thing was a well-documented fiasco that resulted in two exposé documentaries now airing on Netflix and Hulu and six years of prison time for its founder Billy McFarland. Osumi explained his experience being entangled in the doomed festival.

Osumi, who graduated from SU in 2016 with a major in photo illustration, was initially contacted about Fyre by Grant Margolin, a 2014 SU alum and the festival’s eventual chief marketing officer. The two knew each other at Syracuse since Osumi had photographed Phi Delta Theta fraternity events for Margolin.

Osumi photographed a tour during summer 2016 which Ja Rule and Ashanti staged to promote the Fyre music booking app. The app was supposed to operate somewhat like Uber for live musical acts: users could request to book an artist and the artist could approve or deny it, as well as set their own booking fees.

Through his connection with Margolin, Osumi pitched his portfolio to shoot promotional video and other material for Fyre Fest in the Bahamian island of Norman’s Cay. There were two trips, Osumi said, in November and December of 2016 that each lasted five days.

On both of those trips, Osumi shot pictures and video of influencers and models, taking abstract shots and photos of the models when they were free. One of them was supermodel and actress Emily Ratajkowski, who reposted a portrait he took of her to her Instagram. However, Osumi said the plans the production team had, who were in charge of shooting video, were frequently changed or cut.

Influencers on set during Bahamas promo shoot for Fyre Festival.

Influencers post on a yacht during Fyre Festival promo shoot.

“It felt like the management had this grand idea,” Osumi said. “But they weren’t willing to look bad in front of the models by making the models do things they didn’t want to do.”

Osumi said that he and the rest of the team originally scheduled a day to shoot footage of the models at sunset before founder McFarland had a different idea.

“Instead of that shot, we ended up following Billy into the middle of the ocean on three tiny boats,” Osumi said. “All boats were full, and he wanted us to get video footage of him swimming with sharks.”

The conditions were ultimately too rough for McFarland to even get into the water. And, by the time they got out to the ocean, it was too late for the planned sunset shoot. The footage they ended up taking was on a shoreline of another nearby island.

Osumi considered the vision behind Fyre Festival impressive, “but the execution was terrible,” he said.

“I think we did a pretty good job on selling this dream of this beautiful private island that you can come party on, and ‘Look at all these beautiful people you’ll be with’,” Osumi said.

But the expectations didn’t meet reality.

After the first shoot, Osumi said he told his parents over the phone that he would be surprised if the festival actually happened.

“I saw how management was running everything and it just seemed like they weren’t even prepared at all for what they were attempting to accomplish,” he said.

Days before the festival was set to fly in thousands of the attendees and several music acts (most of whom would back out last minute) including Blink-182, Migos and Major Lazer, the production company arranged for all its employees to relocate to the Bahamian island of Nassau. From there, Osumi watched the chaos unfold on Twitter.

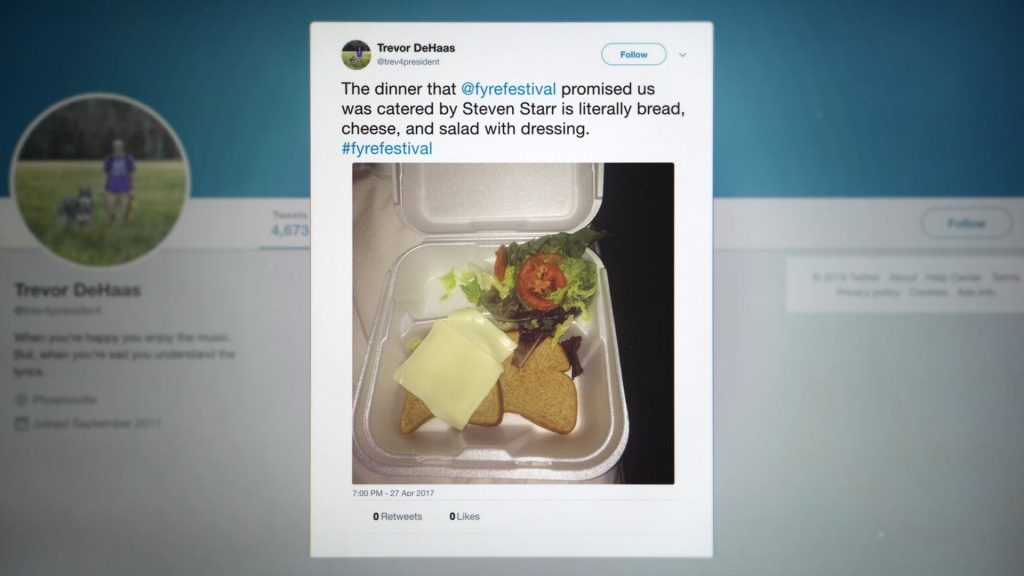

“As soon as I saw the photo of the styrofoam container and the lettuce and bread, I knew that everything was over,” Osumi said.

Osumi, who now works as the chief of staff for MoviePass executive staff, says he doesn’t regret working for the company and said he was at least paid for his work, unlike many of McFarland’s employees involved in the project. He notes he can now spot key signs of a bad business: leadership lacking in self-awareness, a mentality that money can fix any problem, and a value of brand image over the wellbeing of employees.

But also, Osumi adds, “It makes for a good story.”