Striking a virtual chord

Music studios switch to online learning

When all non-essential businesses were ordered shuttered by New York state last month, Rocky Petrocelli was not about to let his students or his 13 self-employed teachers down.

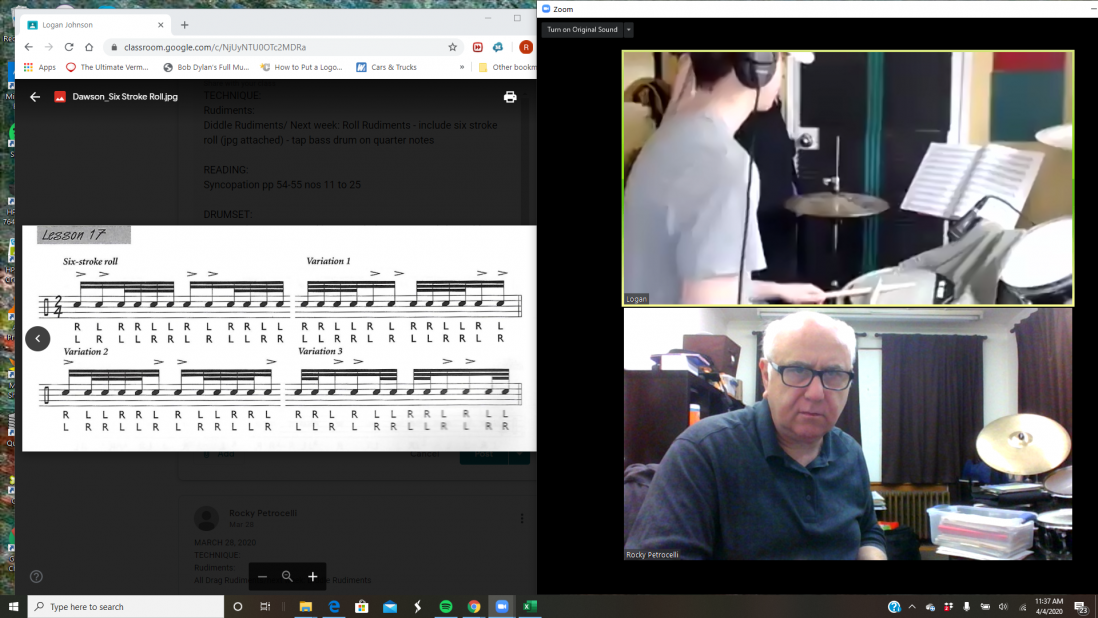

The drummer, music educator and owner of Rocky’s Music Studio in North Greenbush, New York, who has operated the studio and its on-site retail shop since 2005, decided in March to move his drum lessons online and encouraged the other instructors to follow suit. Since they’re not Petrocelli’s employees (though they pay rent for studio space), each teacher decided individually how to continue their work. Most teachers, Petrocelli says, chose the online route because teaching regular music lessons is their main source of income. While the choice to switch was ultimately up to them, he’s keeping in regular touch with each instructor during this unusual time. “I’m sending out emails to everybody every week or two just to see how it’s going,” Petrocelli says. Some teachers have had to work around limitations associated with their webcams and microphones, but Petrocelli said the transition has been fairly smooth overall.

Many music teachers are among the private contractors in the entertainment industry who have found themselves facing a sudden and indefinite income freeze since COVID-19 social distancing requirements took effect. The most fundamental part of their work — sitting together with students in small practice studios and closely monitoring their progress — was suddenly threatened under state-mandated public health measures. Fortunately, the transition to online teaching was already under consideration by the music community. A 2019 study published by Frontiers showed that many musicians are actively seeking out digital ways to address the technical aspects of music — like recording audio and keeping metronomic time — and foster communication between music teachers and students.

Music studios around the U.S. have adapted by conducting music lessons remotely. A Washington, D.C.-based studio called 7DrumCity made a complete shift to online lessons on March 25, but they’re still encouraging new students to join, even if they’re not in the D.C. area. Lesson revenue will help support local musicians who have lost income from canceled performances, WAMU 88.5 radio reported. In Iowa, School of Rock, a studio specializing in guitar, bass, piano, drum and voice lessons, transitioned lessons online in late March, according to We Are Iowa. In the South, WBTV news reported that a music teacher in North Carolina started posting online versions of his music classes on YouTube. And a Los Angeles mariachi school owner with a similar idea is now holding music lessons via video live streams, according to KABC news.

Many university music programs have also shifted online, despite challenges. Blaire Koerner, a bassoon instructor at the Syracuse University Setnor School of Music and the University of Rochester’s Eastman Community Music School, says that sound-canceling technologies built into Zoom, the video-conferencing software that many instructors are using, can diminish instrumental sound quality. “They try to mute background noise and focus on only vocal-based sounds,” she says. “And instruments are considered background noise.” Instrument registers can also make a difference, Koerner said. Instruments with lower registers, like the bassoon, generally sound better on Zoom than instruments with higher registers, like the flute. Users can disable the sound-canceling setting, which makes instrumental sounds easier to hear, but also halts the software’s attempts to reduce true background noise. “If there are siblings running around or anything else, then you get an overload,” Koerner says.

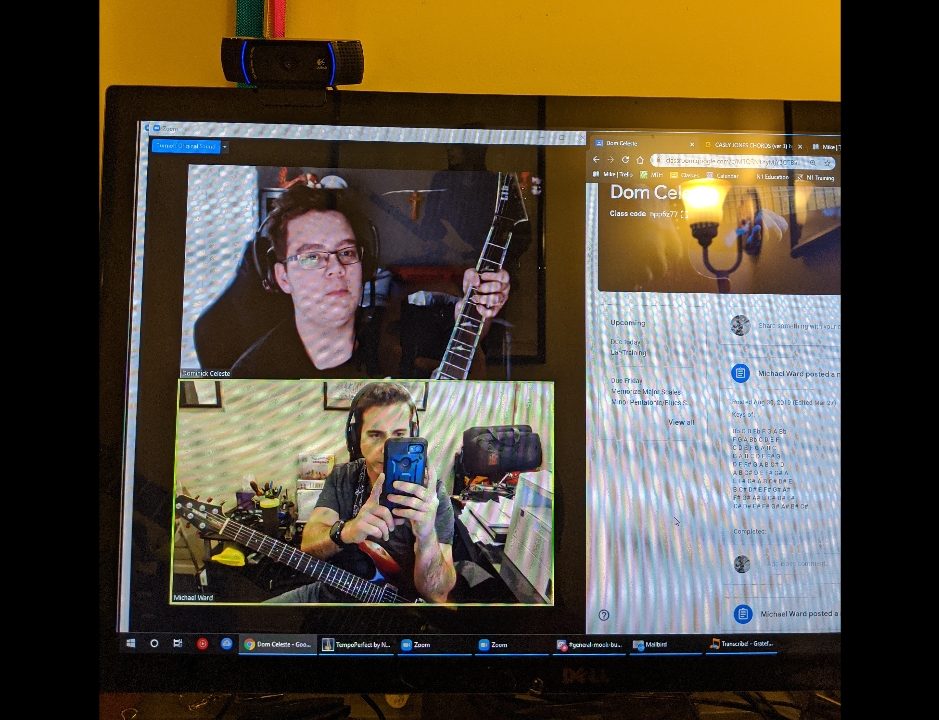

Mike Ward, who has been teaching guitar at Rocky’s for 12 years, uses Google Classroom to organize individual lesson materials, such as sheet music and slowed-down audio tracks for play-along practice. Almost all of his 64 students have kept their regular lesson times, and Ward has continued teaching with minimal interruption. He says he started investigating online music education options long before the coronavirus pandemic, so students who traveled during summer vacation could continue their guitar lessons. “If you’re calm about it and you act like it’s no big deal, then nobody else is going to freak out,” Ward says. “The only thing with music lessons that’s a little hard is you can’t play at the same time, which sometimes you want to do. Even if the internet connection is really good, there’s a half-second lag. But there are plenty of other things we can work on.”

So far, the students and parents at Rocky’s Music Studio have responded well to the online transition. “It’s been very positive because they really want their kids to learn,” Petrocelli says. “Plus, they want to keep them occupied.” Some of Petrocelli’s students have suspended their lessons, because they don’t have the necessary equipment for remote learning. Since most of them prepay, Petrocelli keeps careful records to make sure all payments will get honored. He offered refunds, but so far, everyone has chosen to make up missed lessons once in-person classes resume.

Dominick Celeste, a 16-year-old who started taking guitar lessons with Ward in fifth grade, took some lessons online during his summer vacations before the pandemic began. He says that in addition to his rapport with Ward, using Google Classroom to store and share learning materials has helped the lessons run successfully. Aside from purchasing a webcam for his desktop computer, Celeste hasn’t had to change the pre-existing practice space in his bedroom. However, he’s noticed limitations associated with his webcam. “It’s not very easy to position where you can actually see where my fingers are,” Celeste says. “Like if I’m playing something on the neck [of the guitar] and strumming, Mike can’t see that.” For his entire guitar to be visible, Celeste must move away from his webcam and computer screen, making it harder to see his screen and harder for Ward to watch his technique.

Mike Ward’s online lesson setup.

Mike Ward and Dominick Celeste during an online guitar lesson. Celeste takes his lessons from his bedroom at home via Zoom.

Assessing and improving physical technique is indeed a challenge during online music lessons, agrees Fred Karpoff, a piano professor at the Setnor School of Music and founder of Entrada Piano Technique, a recently relaunched online video resource for piano teachers and students. He says that one of the most important technical details that music teachers should look for, online or in-person, is the student’s posture. Observing posture can be especially difficult in an online setting, but Karpoff says that by maximizing the video chat window size on the instructor’s screen, it can (and should) be done.

While there are no universally established “correct” ways to teach music online, Karpoff expects that the sudden reliance on remote education methods will leave a legacy of quality instruction in the music field, even after in-person lessons can safely resume. “This kind of instruction is going to happen much more often,” he says. “People are going to be more willing and interested to take supplemental lessons this way.”

At Rocky’s, lessons will remain online for the foreseeable future. Though online lessons have allowed teachers to maintain most of their income, the studio’s retail sales have ceased. Petrocelli’s last sale, a pair of drumsticks, took place on the front doorstep. He’s also had to cancel concerts and other events, which the studio organizes several times each year to showcase student progress. Petrocelli and Ward hope to reschedule those events, but the new dates remain ambiguous as the pandemic continues. “The kids were all telling me how disappointed they were, but they know that we’ll do it again eventually,” Ward says. “We’ll figure something out.”

This article is part of the Fermata: Arts and Culture in the Time of Coronavirus series reported by students in the Critical Writing course at the Newhouse School. Fermata features stories on the impact of the pandemic on a wide range of artists and cultural figures, from musicians and comedians to restaurateurs and boutique owners.