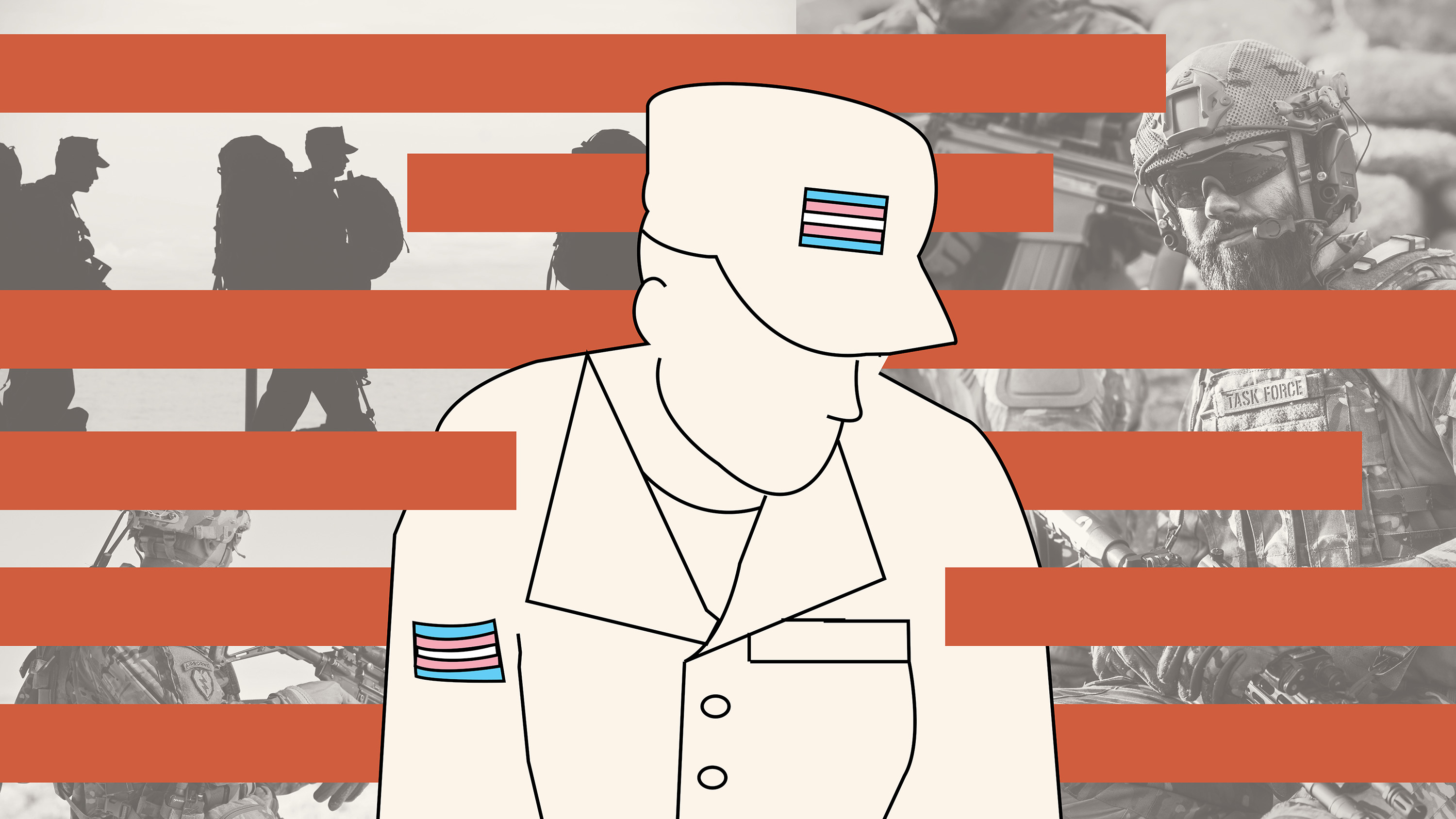

The Right to Fight

The Right to Fight

While transgender people have been historically barred from the military, recent policy changes have allowed them to serve again.

enny Meyer’s time in the military contained many things: war, toxic fumes, and even death. But there was something more personal and hidden about his time in the service, Meyer was a closeted gay man. Before World War I, Congress banned LGBT people from serving in the military, leading many active duty personnel to hide a major part of themselves.

“Every day that I served for 10 years, I had to listen to crude, violent jokes, and commentary about how somebody would kill a queer if they ever found one,” Meyer said. “I had to remain silent.”

While the military allowed LGBT people to enlist, it prohibited transgender individuals for fear of disrupting the service. However, in 2016, the Obama administration lifted the military’s ban on transgender recruits.

U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Bree Fram remembers coming out as transgender to her colleagues at the Pentagon the day after the ban was listed.

“Officers walked over to me one by one and shook my hand,” said Fram who worked in the Pentagon before moving to Rome, N.Y. “They told me it was an honor to serve with me.”

To send an email to her colleagues was a quick way for her to come out as transgender, and Fram regrets nothing ever since. If she had come out before then, the military would have discharged her immediately for something that had nothing to do with her ability to serve.

After the 2016 policy change, the transgender military community (14,700 transgender military personnel, according to the American Medical Association) began to serve openly without repercussions, eliminating the process of being discharged had they revealed their gender identity before 2016.

Additionally, they began receiving proper health care to transition to another gender and were allowed to change their gender identification in the Pentagon personnel systems.

“Transition is something that allows each of us to be our best selves and to remove barriers that exist so you could achieve your maximum potential,” Fram said. “It is simply to be the best version of a professional that they can possibly be.”

In 2019, the Trump administration began banning military applicants with a history of medical transition treatment. The administration also disqualified military applicants who have a history of gender dysphoria unless they have been documented as “stable” after 36 months and were willing to de-transition to their birth sex.

“There is a substantial amount of transgender individuals who would love to join the military and to put themselves in harm’s way to protect the freedoms of the American people and because of their gender identity, they’re precluded from doing that,” said William Robert, director of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Studies at Syracuse University.

Five days after taking office, President Joe Biden issued an executive order reversing Trump’s ban and allowing all able-bodied individuals to serve in the U.S. military. Once again, transgender individuals had the right to enlist, just as they did in 2016.

Transgender service members have no negative impact on military readiness, according to a 2018 report from the Chiefs of Staff of each military branch. But Trump had stated in a White House memo that “retraining troops with a history of gender dysphoria present is a considerable risk to military effectiveness and lethality.”

Trump had also claimed the military spends too much on health care costs for transgender service members. But the Defense Department estimates the military spends $8 million on health care for transgender service members — less than 1% of its $50 billion health care budget.

“What [the military] is doing is denying [themselves] future heroes,” Fram said. “We’re going to fight with brainpower and if they’re in a trans body that is capable of performing the mission I want them in the military.”

There is no medical reason that transgender troops should be banned from enlisting, according to research from groups such as the American Psychiatric Association, The American Medical Association, and American Psychological Association.

“The government thinks that we are a burden on the military, but we must show the world how capable we are of completing the mission at hand,” Fram said. “I think the President did us a favor because he’s shown a spotlight on trans military service.”

A federal bill was introduced after Trump’s policy to prohibit the military from discharging service members or reject military recruits because of their gender identity. The House of Representatives approved it, calling it an end to discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

While the Department of Defense policy prohibits discrimination, the Department allows anyone to enlist who meets all military standards based on their biological sex. The Department also does not allow service members to lose their jobs on the basis of gender identity and strongly protects the privacy of those who identify as transgender.

The Trump administration policy strictly affected those with gender dysphoria, a medical condition when a person feels distressed because of their mismatch between their gender identity and their assigned birth gender.

“I think this was meant to signal a larger form of intolerance and political expediency,” Robert said. “I don’t think that this administration wants to re-navigate the treachery of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ but given the numbers of people in the transgender military community that’s much easier to sustain with much less pushback.”

The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy issued by the Clinton Administration in 1993 directed service members to not be asked about their sexual orientation, but it was also a way to out members of the LGBT community hiding in a place that allowed them to be there, Meyer said.

“It was ‘don’t ask, don’t tell, don’t pursue’ — but they ignored the ‘pursue,’” Meyer said. “Anybody that was suspected was interrogated… and then kicked out.”

Military transgender advocacy groups such as SPART*A, which Fram serves as the vice president of, offer counseling for members who identify as transgender, non-binary, and gender non-conforming. Since the start of the organization in 2013, SPART*A has amassed a following of 1,150 service members.

“What trans people are doing every day is accomplishing the mission around the world,” Fram said. “What they do under pressure is truly amazing, they just lace up their boots and go to work and get the job done. Given their circumstances, this is a testament to their resiliency and their desire to serve in the country they love.”

“It’s very good that Biden restored the Executive Order, but that’s not enough,” Meyer said. “We want legislation, that’s our agenda. We want to make it a law to allow transgender people to be fully equal, serve, and not have the next president revoke it.”