A Lasting Impact

A Lasting Impact

The Syracuse 8’s protest still resonates half a century after their courageous stand for equality in college athletics.

f you see something wrong, call it out.

Greg Allen sees that moral imperative in action when watching students protest for equality on the Syracuse University campus. And it reminds him of the call to action he felt when he and his teammates took a stand against inequality that helped change the university and all of college athletics.

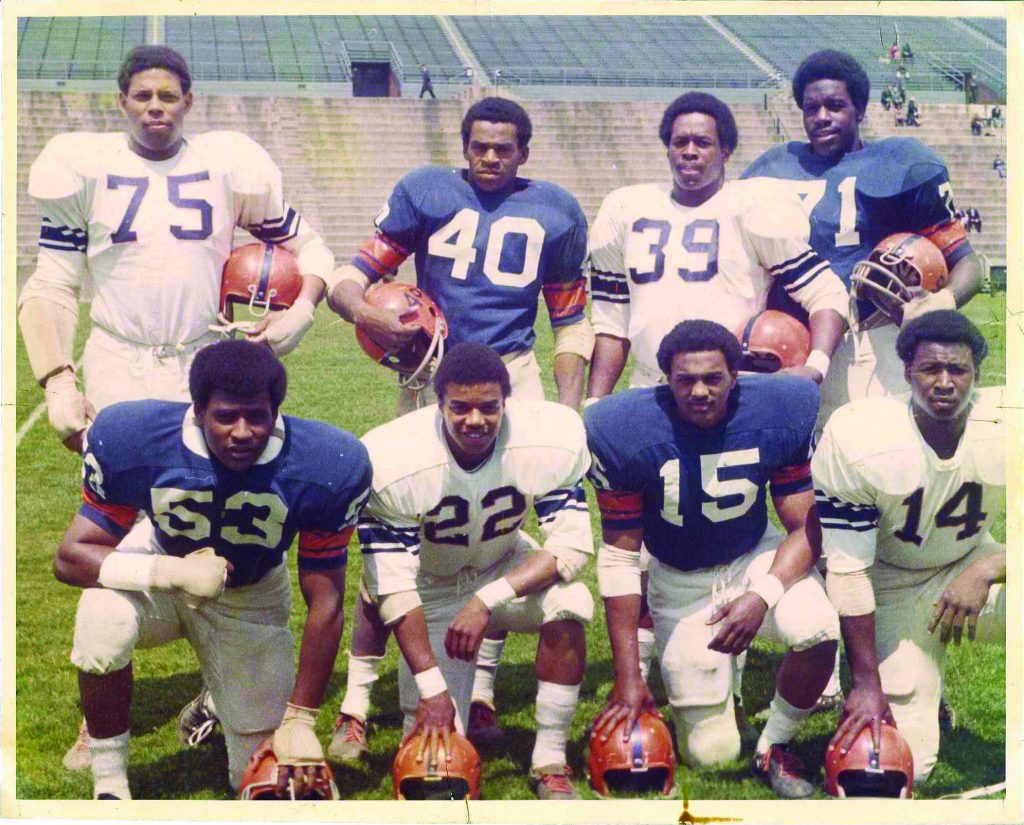

Allen and eight other Syracuse football players, who mistakenly became known as the Syracuse 8, laid bare the systemic racism embedded in college sports at Syracuse University and other college programs when they decided that bringing about social change was more important than playing the sport they loved.

Boycotting a football practice during the 1969 season in protest of white student athletes receiving more benefits than their Black teammates, the Syracuse 8 demanded access to the same academic tutoring as their white teammates, better medical care for all members of the team, merit-based starting assignments, and a racially-integrated coaching staff.

Flash forward to 2019 and students marching in protest of racist graffiti on the SU campus, #NotAgainSU focused not only on the current campus climate, but on the history of racism and racist acts on the campus. Student athletes supported the movement, with SU football players changing their nameplates to read “Equality” and the Syracuse women’s soccer team taking the field with warmup shirts reading “I Can’t Breathe” after the murder of George Floyd, which fueled the spread of Black Lives Matter protests from college campuses to cities around the world.

Student protests like #NotAgainSU make Allen proud of the students at his alma mater.

“I think students are seeing something and saying something,” he said.

Allen is one of six former members of the Syracuse 8 who spoke to Syracuse University students this year in honor of the 50th anniversary of the protest that changed sports at Syracuse, and each of their lives. Allen, Richard Bulls, Dana Harrell, John Godbolt, John Lobon, Clarence McGill, A. Alif Muhammad, Duane Walker, and Ron Womack, ignited the flame when they boycotted a single football practice, believing they were receiving unfair treatment as Black student athletes at Syracuse University.

“I came there like all the other fellas to play football and to get an education,” Womack said. “I was young and naïve and I really thought in playing football that was the one place where things would be fair and it was really heartbreaking when I found out that racism existed everywhere.”

There was a lot at stake for the young players.

“We all knew if we stepped out and we made it vocal, made it public, that we would be one, probably dismissed from the team,” Allen said. “But the other issue was that we were maybe sacrificing our scholarships, our education and the other piece was those childhood dreams and aspirations that we were making a voluntary decision to walk away from. And for me personally, that was very tough.”

But when Syracuse University failed to make a change, all nine members chose to leave the football team for the entire 1970 football season.

“We were called every name in the book,” Harrell said. “There were demands for us to be kicked out of school, kicked off the team, our scholarships were revoked and so forth. Some fans said that if we were ever let back on the team, they would stop coming to games.”

Eventually, a committee was formed to look into the claims the nine football players had made, ultimately deciding “that racism in Syracuse University’s athletic department is real and chronic, largely unintentional, and sustained and complicated unwittingly by many modes of behavior common in American athletics and long-standing at Syracuse University,” according to the 39-page report released after a 10-week long study.

“We challenged the system,” Allen said. “We got a system to change and Syracuse University is a better place because of it.”

That change wasn’t immediate.

“There’s a little naivete in the consequences,” Allen said. “Assuming that once someone investigates your allegations and has proven that your allegations were correct that everyone is forgiven and we go back to square one and start all over again — that’s not the way things worked out.”

Back-and-forth battles ensued between the coaching staff and more progressive administrators, such as then-Chancellor John Corbally. Former head coach Ben Schwartzwalder wanted nothing to do with the findings, dismissing every claim the Syracuse 8 made against him and as a result, little to no change was made on that 1970 football team.

But when Syracuse named their first Black head football coach in program history in 2012, Dino Babers, the last of their demands had finally been fulfilled.

“Oh, that’s fantastic,” Allen said of the achievement. “Everything that we boycotted for is currently the fundamental foundation of what is going on in college athletics, not just in football, but in all athletics at every school. We take very great pride in that. We know that we made a difference not only at Syracuse but nationally across the country in college sports.”

In 2006, all members of the Syracuse 8 were invited back to the university to receive SU’s highest honor — the Chancellor’s Medal — and given the letterman jackets denied to them while at SU.

Sean Kirst covered the ceremony for The Post-Standard and jumped at the chance to speak with the Syracuse 8 after their homecoming.

“Coming back for that medal reaffirmed to them that there were larger things than the athletic court, that there are bigger statements to be made, that there are bigger changes to bring about,” Kirst said. “It meant something to them to come back and know that it was being appreciated institutionally.”

As for Allen, emotions ran high that day.

“For over 30 years, we assumed that our sacrifice had been forgotten,” he said.“When we finally got our ‘thank you,’ it was one of the most emotional moments of my life.”

The graffiti that sparked the #NotAgainSU protests is a painful reminder that there’s still work to do in combating racism at Syracuse University, but the protests themselves remind Allen of his own sacrifice and give him hope.

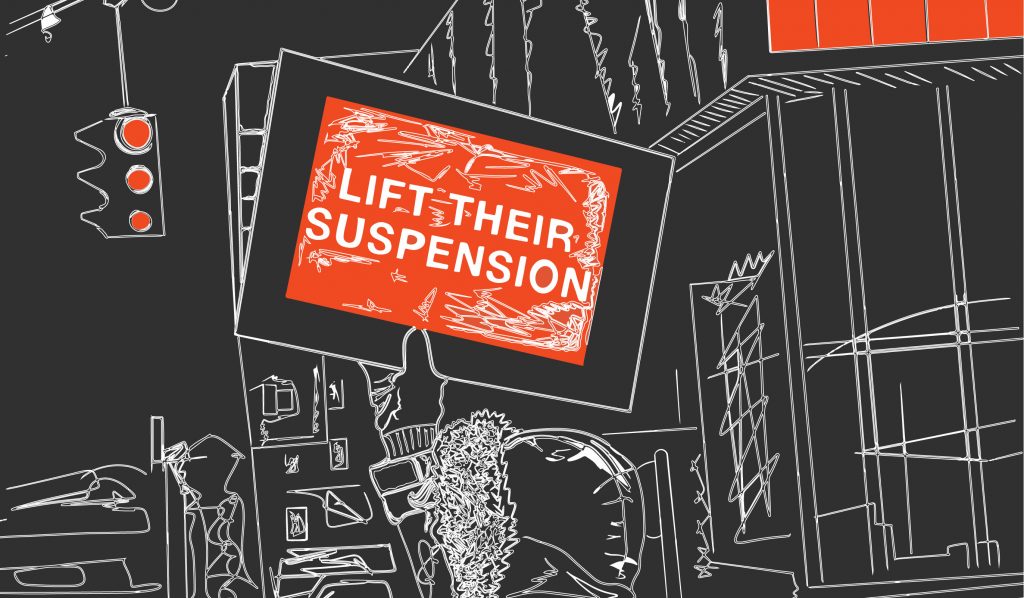

Over the course of 13 days in November 2019, 12 cases of racist and anti-Semitic graffiti were found throughout SU’s campus. Demonstrations consumed the campus, and the protesters handed a list of demands to Chancellor Kent Syverud. While the students’ pleas were initially met with suspensions and restrictions, Syverud eventually rescinded the punishments and pledged change.

The parallels between the protests separated by half a century are clear, Allen said. “I think for what we see on campus, our example serves as a recipe for what can be accomplished at universities when students get together and use their collective voices for something that’s beneficial, not just to a specific group, but to the entire community,” he said.

Allen’s advice — both for that younger version of himself and today’s students fighting inequality — is to prepare yourself for the consequences of your actions.

“We have eight young men with no maritime experience in a rowboat out on the ocean trying to get the attention of the ocean liner so it turns,” Allen said of his own experience standing up to power. “You’re doing it not out of self-preservation, but you’re doing it to actually help the ocean liner get into port. As that ocean liner turns and you get it to turn and there’s that euphoria, it’s only momentary because what you don’t anticipate is the wake once the steamship turns.”

He has no regrets, but wants today’s protesters to better anticipate the resistance they’ll encounter.

“See something, say something,” Allen said. “But be prepared for the consequence.”