Worth a Shot

Worth a Shot

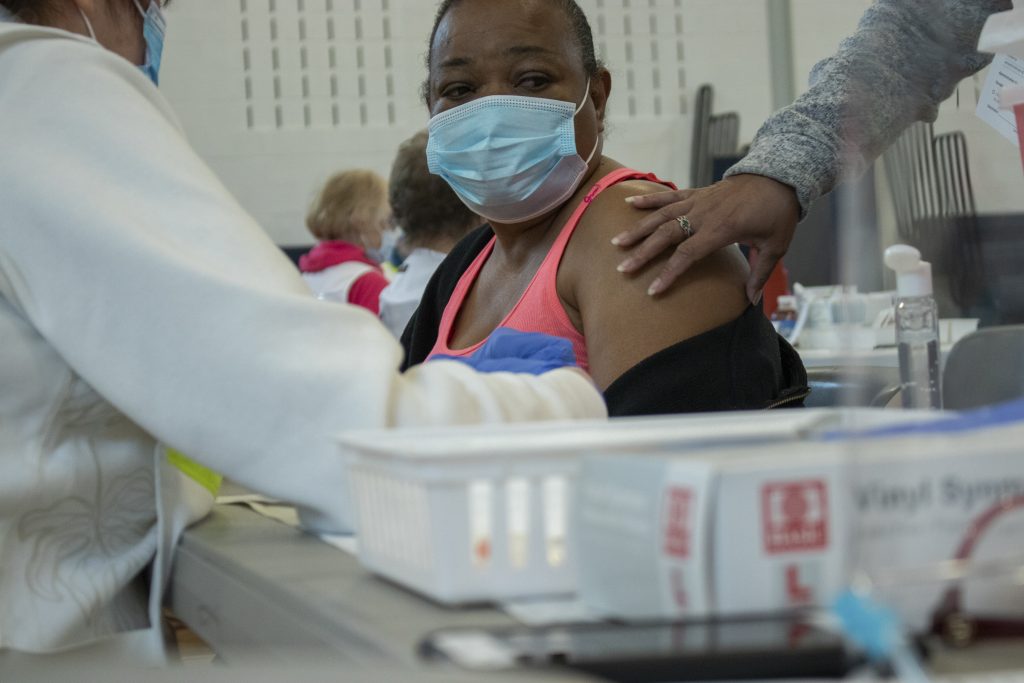

COVID-19 is proven to have larger impacts on racial minorities, causing higher rates of cases, hospitalization, and death.

s the United States endures its second year of a pervasive pandemic, the urgency of delivering millions of COVID-19 vaccines serves as a reminder that the country is still in crisis.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 157 million people in the United States have received at least one dose as of May 15, which is about 47.4% of the total population, and nearly 37% has completed the vaccine series.

In central New York, more than 472,000 people have received their first dose as of May 15, with more than 418,000 people fully vaccinated, according to the New York State Department of Health.

Despite a positive trend in overall numbers, there is an alarming pattern within the data about COVID-19’s impact on racial minority communities. The number of vaccines administered to people of color, as well as higher percentages of confirmed cases and deaths within these communities, reflects this unbalanced trend.

First Dose Vaccinations by Race in Onondaga County

As of May 15, these are the percentages of residents in Onondaga County with at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose by race and ethnicity.

Public health experts suggest that among several factors that may explain the disparity in the vaccination rates, the undercurrent of systemic issues and racism toward different races and ethnicities in the healthcare system is problematic.

Hard hit at home

Since the first COVID-19 case was reported in the United States in January 2020, the numbers documented by Johns Hopkins University and The COVID Tracking Project are staggering: Over 32 million cases were reported as of late April. More than 170,000 people were hospitalized in 2020. More than 566,000 lives were lost.

As COVID-19 surfaced locally and waves of cases rolled in the past year, the hospitalization and death rates have been higher for racial minority populations.

Of Onondaga County’s 460,000 residents, about 4% are Asian, 11.4% are Black, 5% are mixed-race, and the remaining 80% of the population is classified as white. (Latinos are often categorized as white unless statistics are based on ethnicity.)

As of May 15, the 14.5% hospitalization rate and 13.3% death rate of Black people both exceed the population percentage, according to the Onondaga County Health Department. The death rate of Asians is also higher than their population percentage, while the hospitalizations are slightly less. Neither rate for white people is higher than the population percentage.

COVID-19 Death and Hospitalization (Onondaga, NY)

As of May 15, these are the population and COVID-19 reported death rates in Onondaga County, New York, based on data collected by the County Health Department.

Rebecca Shultz, the director of community health at the Onondaga County Health Department, said cases initially were tracking higher among the white population because they were traveling to other states or countries where outbreaks were happening. The trend changed after state and county lockdown restrictions went into effect last spring.

“Once the stay-at-home orders were sort of handed down, we started to see a bit of a shift in the demographics of our cases toward individuals because of the nature of their work and their socioeconomic situation,” Shultz said.

Dr. Christopher Morley, chair of the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at SUNY Upstate Medical University, said Syracuse’s standing as one of the poorest cities in the country makes distinct divides between rich and poor, as well as along racial and ethnic lines, that become more apparent during a pandemic.

“We obviously are talking about a virus disproportionately affecting African Americans across the country, and these two things (poor socioeconomic status and high infection rates) go hand in hand,” Morley said. “One thing that we have seen in the literature is that when you adjust for socioeconomic status, those (infection) effects tend to be mitigated.”

Morley complimented Onondaga County’s leaders for backing state health officials’ lockdown mandates and restrictions while recognizing that it has been a considerable hindrance for businesses in lower-income neighborhoods.

“It puts restrictions to lower the number of people in the business, which keeps those individuals safer as well,” he said.

Shultz said throughout the pandemic, the county health department has tried to factor racial minority communities into decision-making, noting that the first COVID-19 testing center opened at the Syracuse Community Health Center on South Salina Street.

“It is in a neighborhood that is relatively easier to access for a lot of the individuals who live on the South Side of the city where a higher proportion of Black and African American residents are located,” she said.

Along with setting up testing centers and making similar considerations on upcoming vaccination locations, Shultz said the county has tried to offer residents basic medical supplies like thermometers and living needs like food if they are unable to get them during imposed lockdowns or individual quarantines.

Numbers soar for New York, nation

As of mid-May, the New York State Department of Health reported that — in New York state, excluding New York City — the death rates of Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations, per 100,000 people, were 120.2%, 90.4%, and 33.6% higher than the white population, respectively.

COVID-19 Actual Mortality Rate (NY)

As of May 15, these are the COVID-19 actual mortality rates (per 100,000) of different races in New York (excluding New York City) based on the data collected by the New York State Department of Health.

Social science researchers Thomas Selden and Terceira Berdahl have been looking for specific health-related factors to explain the disparities and found that the household makeup may be a contributor. Black people with a high risk for severe illness like COVID-19 were 1.6 times more likely than white people to live with someone who works in the healthcare field.

Nearly 65% of Hispanic adults with the same high risk of contracting severe illness were more likely to live with someone who needed to leave home for a job thus putting themselves at risk for exposure while in public. This compared to about 57% for Black adults and about 46% for white adults.

Selden and Berdahl did note that while Black adults were more prone to have specific health risks tied to COVID-19, white adults on average live longer so were more at risk simply due to age. Asian and Hispanic populations trailed both groups when it came to health risks.

During a keynote address at the Health Justice Conference 2021 in January, Dr. Uché Blackstock, the founder and CEO of Advancing Health Equity, discussed how many racial minority individuals working in fields that require interaction with others, such as healthcare, public transportation, and postal services where they may not always be able to shield themselves from COVID-19 risks. She said that these people composed the majority of her patients at the beginning.

Besides employment situations, Blackstock said that minorities with larger families may reside in the same house or apartment in which tighter living quarters also could increase the chance of being exposed to the coronavirus.

Testing also lagged in poorer and more racial minority-concentrated communities during the early months of the pandemic because these residents weren’t considered likely carriers in comparison to those who had visited potential hot zones in Asia or Europe, Blackstock pointed out.

“People whom I was caring for in central Brooklyn were not traveling to those places,” Blackstock said. “So as a result, they were not being tested.”

Even bigger issues rage

Dr. David Ansell, the associate provost for community affairs at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said America’s history of socioeconomic disparity that determines how healthy or how long people live has become even more apparent in the COVID-19 era.

“All of the American medicine is built on a foundation of white supremacism,” Ansell said during January’s HJC 2021. “If you’re in the top 5% of the income in the United States, it doesn’t matter where you live; you’re going to have a long lifespan.”

“The rich live.”

Both Ansell and Blackstock referred to the iceberg model during their conference talks, suggesting that racist acts against individuals may be seen above the surface, but larger systemic racism remains pervasive in healthcare and society because racist factors like mass incarceration and types of segregation are too ingrained into the society to be noticeable.

Therefore, while hospitals, medical professionals and healthcare providers across the country and here in central New York are dealing with a raging pandemic, they are also grappling with the structural and systemic issues, which create bias, that directly affect people of color.

“If we want to address health disparities, including those seen in COVID-19, we have to address fundamental societal fairness issues and how we treat our fellow humans,” Upstate Medical’s Morley said.

A shot at doing better?

In March, The Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California released its research based on people’s race and level of education and how those factors may reflect people’s willingness or hesitancy to be vaccinated among different racial groups.

This study of approximately 9,000 people found that only 7% of Black and Latino adults without college degrees had been vaccinated and only 13% and 19% of those with college degrees had been vaccinated, respectively.

When it came to those considering a vaccine, less than half of Black respondents with or without college degrees were willing to while Latino adults were slightly higher in both categories.

Vaccinated and Willingness to Get Vaccinated

For U.S. adults aged 18 or older, education plays a signficant role in those who get or want to get a COVID-19 vaccine based on a University of Southern California study in March.

Nevertheless, having a college degree still may not overcome natural human tendencies among some populations because people may be concerned about the vaccine itself.

“My experience is that there may be some hesitancy,” said Dr. Sharon Brangman, the department chief of geriatrics at SUNY Upstate Medical University. “But when we as healthcare providers and healthcare systems take the time to explain the vaccine and answer questions, people change their minds and decide to go ahead and take the vaccine.”

To address the hesitancy, Brangman has been meeting with local Black community leaders to help educate residents including youth who may consider themselves less at risk for infection.

Along with providing accurate information through educational efforts, accessibility is another issue that Brangman and many local medical professionals have been working to address.

Brangman pointed out that the larger vaccination sites such as the Oncenter and New York State Fairgrounds require people to make an appointment online, which may not be possible for everyone, especially elderly residents who don’t have Internet access to the Internet or know how to register.

First Dose Vaccinations Administered by Race in Syracuse

As of May 15, these are self-reported data that only include individuals vaccinated by the Onondaga County Health Department.

To overcome any technology hurdles, county health officials have staged pop-up clinics where local residents can call in advance or show up and register on site. The first pop-up clinic in late January at The People’s African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in the South Side provided the first vaccination shots for 271 residents, and subsequent clinics were held at locations such as the Boys and Girls Club on Hamilton Street.

Brangman said additional outreach and removing registration obstacles can help generate good word of mouth, which could help increase vaccination rates in racial minority communities.

“A lot of people want to wait and see what others experience before they do it themselves,” she said “I find that once information is provided and questions are answered, people start to feel more confident about making a decision to take the vaccine.”