College educators evolve their approach to AI for the 2023-24 school year

College educators evolve their approach to AI for the 2023-24 school year

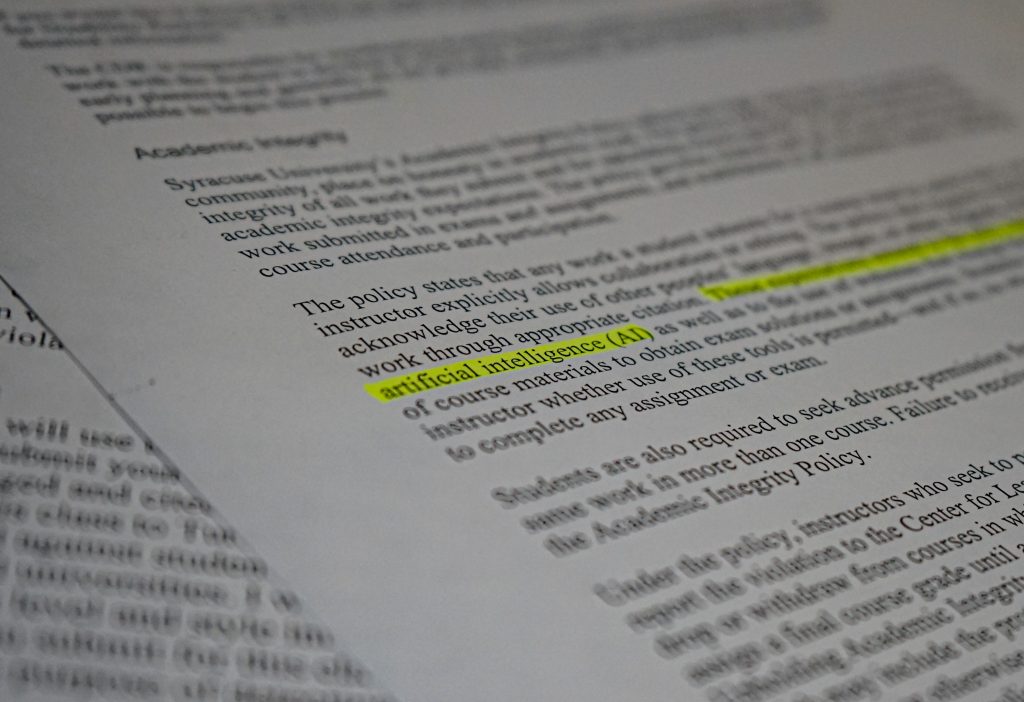

Last school year, artificial intelligence “caught a lot of educators by surprise.” This year, educators at universities shifted their approach to AI in the classroom, considering learning targets and preparation for the workforce.

The 2022-23 school year featured the emergence of ChatGPT, a generative artificial intelligence program that exploded in popularity and posed new questions about education.

Prior to the 2023-24 school year, the first full school year with AI, educators reconsidered how to approach the school year with the technology looming over their heads.

“I think at first it was really confusing, it wasn’t very palpable,” Margaret Usdansky said. “Now I think people have a bit more of a sense of what it is. The sky hasn’t fallen.”

Usdansky is the interim director of the Center for Learning and Teaching Excellence (CTLE) at Syracuse University, a faculty-focused office that offers support for teachers through various services and “promotes effective, inclusive, innovative teaching,” according to the CTLE website.

Before the fall semester, the CTLE put together “Peer-to-Peer Advice: A Timely Conversation with Faculty Colleagues,” a set of recorded conversations with professors of different studies discussing different aspects of teaching with AI.

These conversations demonstrate an evolved approach to AI in the classroom. Although academic integrity issues continue to arise, some educators seek to look beyond those discussions and attempt to ask deeper questions about AI.

“Most faculty we work with are convinced that these tools will become ever more present in our lives, and especially the lives of our students. So questions surrounding how to use them ethically, equitably, accessibly and critically are all being discussed,” Rob Vanderlan, the executive director for the Center for Teaching Innovation at Cornell University, said in a written statement to the reporter.

The Maxwell School of Public Affairs’ Autonomous Systems Policy Institute (ASPI) – a department founded on interdisciplinary research and response to emerging technologies – has been researching technologies like AI since 2019. Because of institutions like ASPI, Syracuse has been at the “forefront” of technical and policy-based AI research, according to Baobao Zhang, a professor studying the governance and ethics of artificial intelligence.

Zhang, a member of ASPI, and other researchers are combining their research to publish The Oxford Handbook of AI Governance, which is coming soon. Similarly, Cornell assembled a generative AI committee that created a report: Generative Artificial Intelligence for Education and Pedagogy.

Higher education’s AI research is matched with in-classroom AI planning based on concerns from faculty regarding AI’s impact on student education and preparation for the workforce.

Usdansky urges educators to “start by thinking about your learning objectives, what’s going on in your discipline, and what students need to know in your discipline.” Cornell’s ICA approaches AI with a focus on “developing foundational skills and knowledge,” the factor which according to them, should determine whether AI is embraced or rejected in a course.

Zhang assigns in-person, hand-written midterms and finals, both to prevent AI use and to emphasize student learning in her American politics class. She approaches AI how a math teacher uses a calculator – not allowing it in the early stages of learning to emphasize student growth and then introducing it as a tool later. She’s concerned about what AI is doing to the workforce.

“AI could be a threat to higher education in terms of changing how we work and how we are trained for the labor market,” Zhang said. “For a long time, I think economists predicted that automation would more likely impact those whose jobs don’t require a college degree. But it has become more apparent in recent years that it might be easier to automate digital services, writing and creative arts.”

Roger Hallas, a Syracuse English professor and one of the educators in the CTLE’s Peer-to-Peer Conversation described himself as being “in the middle” of the AI debate. He has banned it in some of his film classes and highlighted it in others to teach a “larger pedagogy of information literacy, which is in the strategic plan for the university.”

Hallas has similar worries to Zhang about AI and the post-college job market.

“I think so many students… think AI is their friend because it can help them, but once they graduate, what AI is actually doing now is eliminating many entry-level jobs,” Hallas said. “So AI is actually, for the college graduate, a competitor.”