Commentary: Fleeing in fear, landing in chaos

Commentary: Fleeing a pandemic

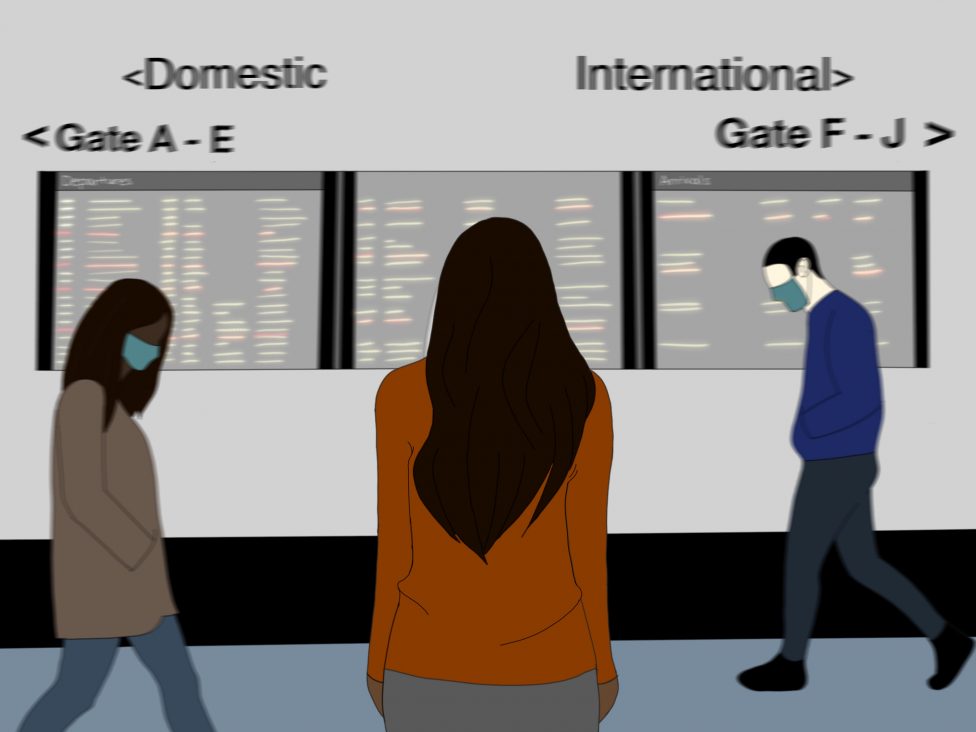

I glanced around me, at the people rushing around the crowded international terminal at JFK. It was always filled with people in a hurry. But today there was an underlying current of fear. There was a global pandemic on the rise, and America, the land of milk, honey, job opportunities and higher education, had people fleeing as opposed to clamoring to be let in.

It was March 18, and the state of New York was approaching a potential lockdown as the virus spread. I was a few days into spring break and had been wondering if I should stay or return to my home in India. I decided that it made no sense to stay in the United States. I couldn’t attend class, I couldn’t go out to report stories for class, and staying in America was expensive. It was cheaper to buy a plane ticket home. Furthermore, my parents were scared. They were much more comfortable with me being home, where they could ensure I stayed in an isolated environment.

I had booked my ticket just the day before. Had things gone as planned, I would have been boarding a plane to Los Angeles for spring break, a trip I had painstakingly planned and saved for. Instead, I was fleeing from a pandemic that ravaged lives like a tornado. In an ideal world, I would be returning to India with my master’s degree from Syracuse University, my bags filled with iPhones, perfumes, and American chocolate, items that cost exorbitant amounts of money at home and gifts that any self-respecting Indian would bring back for her family. Instead, in the little time I had, I bought a few presents from Target and the University Bookstore. I was returning home from abroad. It would look bad if I didn’t bring at least a few presents, a global pandemic notwithstanding.

Around me at the airport, people sat slumped on the floor. At the Emirates counter, a man begged for a ticket. He was willing to pay double. Economy class, first class, the baggage hold, anything. Students in college hoodies dragged around bags upon bags, the lives they had tried to make for themselves crammed to fit airline requirements. It was a crisp day outside, the sun shining brightly over the Queens skyline. But the airport was muggy and airless, much like the hopes of the travelers themselves.

I had left a cold, sunless Syracuse in a hurry. Just several hours earlier, my mother had panic-called me, telling me to leave. The Indian government, she said, had put out a notice saying that any traveler flying through the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, or Oman would be put into government quarantine if they began their journey to India past noon GMT on March 18. The Indian facilities would likely have been in a common emergency room, a dormitory-style room with no isolation at all. Despite having no signs of the coronavirus or any other illness, being in that room alone probably would have made me sick. “Come home now,” my mother had said. “Before things get even worse.”

The only flights to India had layovers in those countries. If I hurried, I could just barely escape the quarantine. I managed to book a flight that would leave New York in time.As I stood in the security line at JFK, I thought about what I was leaving behind. My apartment in Syracuse with most of my belongings, the coffee shops I frequented, the job prospects I may be removed from. I boarded the flight and, as we ascended, I looked out at New York City, which shone brightly beneath me, a carpet of lights and dreams. Ever since I was a child, I had envisioned living and working here. Was I letting go of my dreams in a moment of panic? The thoughts overwhelmed me, so I wrapped myself in the airline blanket, made a little pillow out of the seat cushions and went to sleep.

Thirty-six hours after leaving Syracuse, I landed in Chennai, a city of over 10 million people on the southeastern coast. My hometown.

I was herded into the immigration line. The jammed line inched forward. I was exhausted from jet-lag and the whirlwind of events. A masked nurse checked my temperature. An immigration official examined my passport and I signed declarations for both the health ministry and the city of Chennai that I was not running a temperature, did not have a cough, and would put myself in voluntary home quarantine. I then dragged myself out of the airport into the warm, muggy Chennai air and the arms of my parents, who squeezed a drop of sanitizer on my palms and then gave me a hug.

It was 3 a.m. The streets of Chennai seemed fine, the traffic similar to the times I had come home late after studying or at a friend’s house. The city lacked the sense of panic that New York had. The next morning I woke up to the smell of frying onions as my mother made poha, flattened rice tossed with onions and chiles, flavored with mustard and turmeric. It took me back to all those days when I’d wake up for school. It felt like a sense of normalcy.

As I sat at the table, my mother put a glass of milk in front of me. “Drink it, or else…” she trailed off, leaving the consequences unsaid. It was a phrase I had grown up hearing. Today, it felt familiar, yet misplaced. I didn’t feel like I was supposed to be here. I wasn’t the only one who thought that. Our cleaning lady came in at her usual time, jumping in fright and surprise when she saw the daughter of the house, who until yesterday was supposed to be in America, sullenly sipping a glass of milk. Little differences reinforced my sense of dislocation, such as my father working from home. In the 22 years that he’d worked for the State Department, he had never brought work home.

The Prime Minister was scheduled to address the nation that night and I wondered what he’d have to say. The man was known to make unexpected announcements. His speech started innocently enough as he encouraged citizens to distance themselves socially and stay informed about the virus and its developments. He also encouraged what he called the Janta (people’s) curfew, on Sunday, March 22. The plan was for citizens to voluntarily impose a curfew on themselves to promote social distancing. They’d stay in their homes from 7 in the morning until 9 at night. In keeping with the world’s spirit of honoring emergency workers, he asked that at 5 p.m., Indians stand on their balconies or front yards and clap, ring bells or bang pots and pans.

As the Prime Minister finished his speech, my father muted the news bulletin and sat down next to me on the couch. “You do realize that India could be blacklisted, right?” he said. “You may not be allowed to re-enter the United States.” I nodded and let him pat my head. Maybe it was jet lag, maybe I was just numb, but the thought that I had probably lost all that I’d spent the last few years working for, hadn’t registered. In degrees, it was now becoming all too real.

The hour arrived for the honoring of the workers and the country broke into celebration. Except that Indians being Indians, we took it a step further. In fact, we pushed it over the top and off a cliff. People banged pots and pans like they were in some sort of manic brass band. Some burst firecrackers, some came out in the streets to dance. The whole idea that this revolved around combatting a respiratory disease that spread with the slightest human contact was disregarded. I rolled my eyes. It was a familiar chaos.

I watched quietly from a distance, standing at my balcony. What was supposed to be an honorable act turned into an exercise in noise pollution. I turned and walked back inside. At least I had a balcony. My thoughts went back to my room in Syracuse, a cubicle with a bed, desk, chest of drawers, and a lamp that someone had left in the lobby of my building and I’d picked up. I sat down on my bed. In the next room my parents were in the midst of an argument about whether the cat had been fed. I opened my laptop and began drafting another cover letter, applying for a job that may not exist in a world I may no longer be allowed into.

It was like jumping from one form of chaos to another.

Editor's Note:

This article was recognized as a winner for the CCC Awards for students covering the coronavirus on April 21, 2020. Congratulations, Shrishti!