Black History Month celebrations continue with ‘Black Supernovas’ lecture

'Black Supernovas' lecture continues SU Black History Month

Black history, queer culture, and the politics of fashion.

These are Eric Pritchard’s three favorite things. And through them, the black supernova emerges.

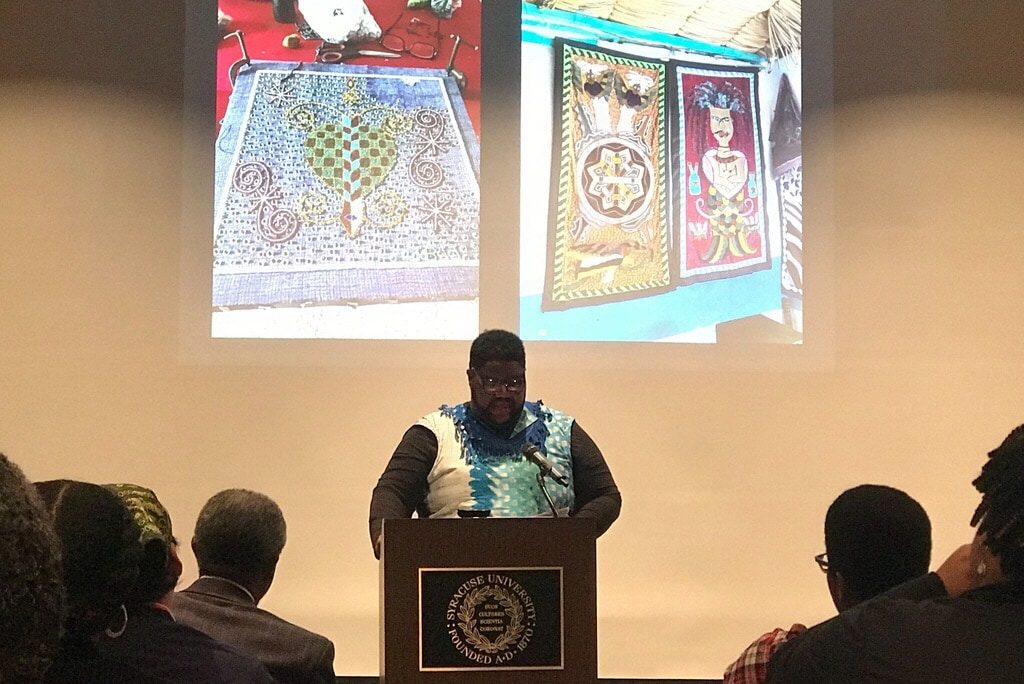

On Feb. 19, Pritchard delivered his guest lecture on black, queer influence in fashion. The event was hosted by the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and is part of Syracuse University’s celebration of Black History Month.

Pritchard spoke at the Schine Student Center on Wednesday night. Chancellor Syverud was among the numerous guests who filled the room.

Pritchard’s lecture is derived from his 2016 book, Fashioning Lives: Black Queers and the Politics of Literacy. Titled, “Black Supernovas: The Legacies of Black Gay Fashion Designers,” his lecture focused on intersectionalities – black influence in fashion, how that influence has been erased.

“Erasure of black queerness,” Pritchard said, “is a form of epistemological violence.” And as he explains, this violence causes far-reaching and widespread harm.

As a child, Pritchard says he was attuned to the role fashion held within his community and others like it. Though low-income, people of color might have lacked the means for luxury, they were bursting with ingenuity. “Black people,” Prichard said, “are arbiters of style.”

The power of style is what attracted a young Pritchard to fashion. He would watch his mother and grandmother, his earliest style influences, and note the way the clothing would transform them. “A euphoria would come over them as they got dressed,” Pritchard said.

“Maybe you were going to church, maybe a wedding, maybe a baby shower,” Pritchard said. “Maybe you were just sitting on the stoop waiting to be seen so you could ask ‘Do I look good?’”

The answer was always the same,” he said. “Yes. You are beautiful.”

Pritchard’s lecture also addressed the erasure of black contributors to fashion.

“I always knew stylish black people,” Pritchard said, “but I didn’t know black people who started and ran their own fashion labels.”

Pritchard went on to tell these erased stories of black fashion pioneers, like Elizabeth Keckley, seamstress to Mary Todd Lincoln and fierce abolitionist. Underscoring the intersections between fashion, politics, and culture, Pritchard argued that “black designers are descendants of abolitionists.”

Indeed, black craftsmen who gain notoriety are disruptors.

Pritchard concluded his lecture with the story of renowned designer, Patrick Kelly.

Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Kelly attended segregated schools most of his life. According to Pritchard, Kelly went to the Parsons School of Design on a merit-based scholarship intended for Irish students.“ His last name was Kelly so admissions assumed he was Irish.” Pritchard said Kelly eventually moved to Paris with a plane ticket from an anonymous benefactor.

Drawing inspiration the way his grandmother would resew his buttons, Kelly used different colored buttons throughout his designs. This became his signature.

Kelly’s career propelled after a six-page, color spread in Elle magazine. Bergdorf Goodman purchased his subsequent collection.

Kelly became the first African – American admitted into France’s prestigious trade union known as Fédération française de la couture.

Prichard displayed a photo of the designer and his grandmother, taken during Kelly’s return home following stardom. In it, Kelly dons a hat that reads “Paris.” Ethel Rainey, his grandmother, wears one of his famous button designs.

“I love this picture because you can see the queer disruption,” Pritchard said. “We see Patrick tied to his roots, and his grandmother showing us the industry that was not prepared for them.”

While Pritchard admitted Kelly’s designs have been controversial – particularly his use of red lips and dark skin – he also pointed out the complexity of self-expression.

“I can recognize that he was engaging in a work of reappropriation,” Pritchard said.

Kelly’s fascination with black iconography was publically known. In 2014, the Philadelphia Museum of Art showcased some of Kelly’s collection of dolls in their exhibit, “Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love.”

Despite his controversy, the designer occupied a space that was traditionally closed to those who looked like him. Kelly paved the way for other black queer designers. In this way, Pritchard believes that Patrick Kelly is a black supernova.

This, he said, is what black supernovas do: “They briefly illuminate and give light to those around them, exploding into black history.”