The pandemic gap year

A COVID year off-campus

Even though Madison Tyler, her younger brother, and mom were in Los Angeles, she would often be able to hear the former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo in the mornings through her television.

“That just got stressful because I was just like, I cannot watch the news all day and I’m in the house and I have to be home to do my work and stuff,” Tyler said.

Tyler was one of many Syracuse University seniors who time away from campus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

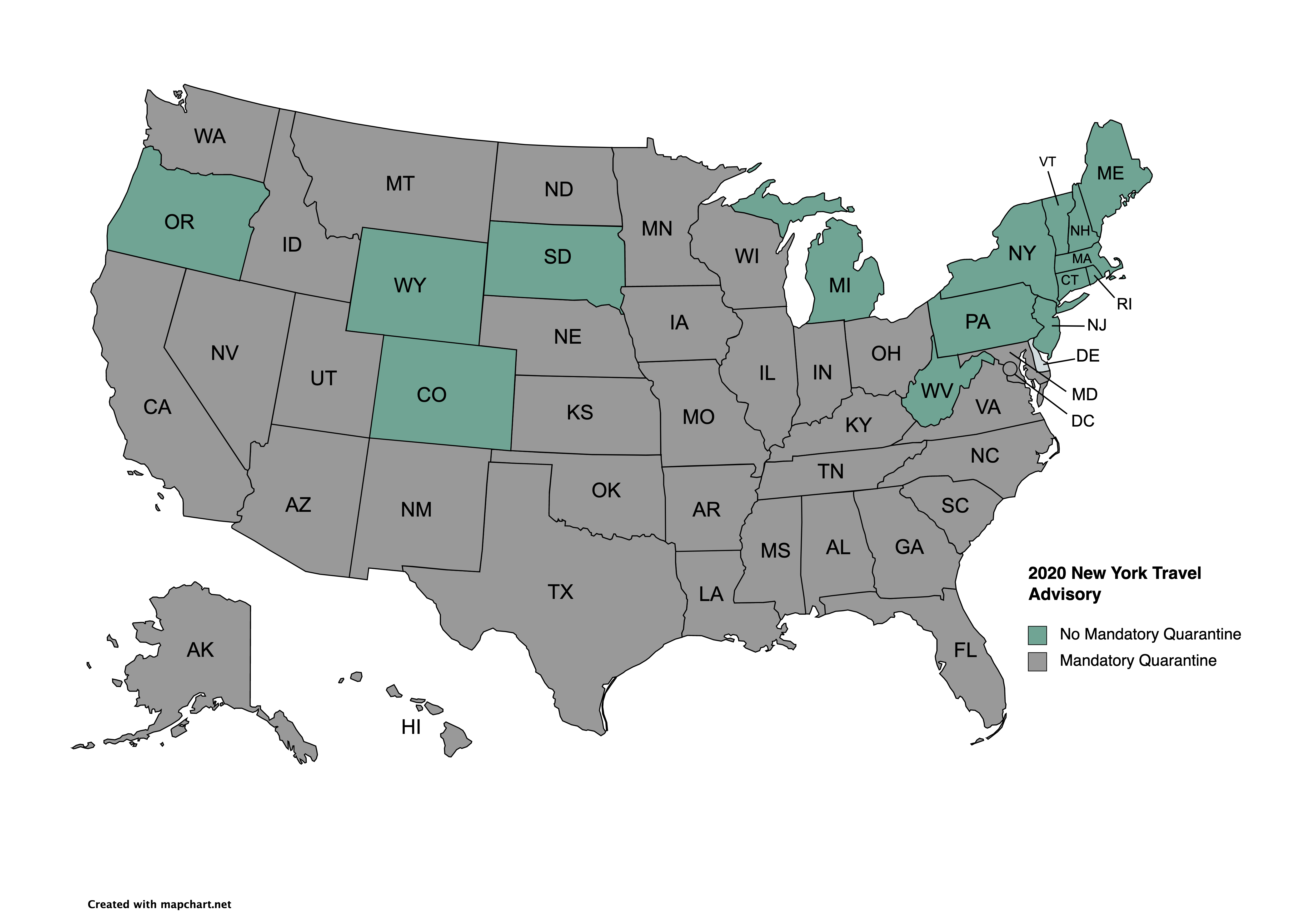

In Tyler’s case, she said she didn’t have enough time to choose whether or not to come back to campus in the fall of 2020. Students from states on New York’s travel advisory list had to quarantine for 14 days — in either New York or another state that was not on the travel advisory list — to come back to campus as a part of Cuomo’s travel advisory decision in June 2020. This cost came out of students’ pockets, and for many wasn’t worth the cost in addition to the uncertainty of what the fall semester would bring.

“For us, we were like I don’t know if I can afford to go quarantine somewhere for such and such amount of days,” Tyler said. “My mom was worried about eating and the food being brought to the room like all that sort of stuff.”

Several factors contribute to why students decided to take time off or even drop out from a university during the pandemic. High tuition prices with no in-person opportunities, the flexibility of online learning, mental health challenges and financial setbacks due to job loss during the height of the pandemic led many students to seek alternative options to a traditional four-year education. Some students who left school during the pandemic never even came back. The National Student Clearinghouse reported in January 2022 that 1 million fewer students were enrolled in college than before the pandemic began.

Richard Mendez, the lead academic advisor at the Newhouse School, remembers that one of his students lived on a family farm and struggled to balance school work with helping his family. Mendez introduced the possibility of taking a break, taking a leave of absence, taking a semester or even two semesters off before everyone was able to be back in person.

“The door is never shut for students that are taking a leave of absence,” Mendez said. “So that was another thing like, if I go take a leave can I come back? Absolutely. So that was a conversation we had to have with students who were reluctant to be like oh I don’t want to leave school right now.”

SU senior Caroline Casey took advantage of being at home with her family in Florida during the spring of 2021 after that fall semester challenged her mental health.

In an attempt to maintain a routine and ease her anxiety, she said she would constantly try to schedule gym time at Ernie Davis. Sometimes, she added, the spots would book up by 8 a.m. so her dad would schedule them for her when he woke up at 6 a.m.

When she went home for winter break she packed up all of her stuff in case COVID numbers rose on campus and students couldn’t return for the spring semester. Once she was home she began to realize that she wasn’t going to have a good experience on campus given the pandemic.

“If I didn’t leave when I did, I don’t know how sad I could have stayed for how long,” Casey said. “And it probably would have gotten worse.”

Mental health implications

For college students, the isolation of mandatory quarantines was compounded by missing out on a chunk of time that was supposed to be dedicated to social and emotional development. This led to a rise in mental health problems. The National Institutes of Health reported in 2021 that nearly half of Americans reported symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder.

Afton Kapuscinski, clinic director for SU’s Psychological Services Center, said that data indicates that women and transgender individuals are at a higher risk for depression. She also saw this high risk in people “with marginalized sexualities, multiracial respondents, people with disabilities, and the 18 to 29 age group.”

For students like Tyler who didn’t live in the strict confines of dorm and campus life, the pandemic still brought with it these mental health struggles. She was waking up at 6:30 a.m. Pacific Standard Time for her English class, going to class all day and doing homework at night to keep up with East Coast Time.

“That was pretty hard, waking up and being present and showing up and then that had sort of a negative effect on my mental health because I would be still staying up late to finish homework and stuff, but then getting up really early to show up to class,” Tyler said.

Kapuscinski said the Psychological Services Center there has been an increase in the volume of people seeking mental health services.

“In general stigma has reduced over the past couple of decades with seeking mental health care,” Kepuscinksi said. “But what I can say is that seeking services has greatly increased, that we have a lot more calls now than we used to and that is consistent with what we see across the country. That the demand for mental health services skyrocketed, particularly in 2020 and 2021.”

Alternative situations

Completing a degree from home and traveling may have been an option for some but others faced too many roadblocks as a consequence of the pandemic.

Cheyenne Chauvin-Pacheco works in SU’s College of Professional Studies as a part-time residential admissions and academic advisor. The part-time residential students she works with are often non-traditional students, meaning they’re 24 years or older and often have spouses, children and jobs that prevent them from taking a full-time course load.

When the pandemic hit many “stopped out” or didn’t return to school because they had to be caretakers for their children or because of the shift from in-person studies to online learning.

“A lot of times specifically part-time students need their support system because they are the support system for many other people,” Chauvin-Pacheco said. “So when you lose that face-to-face aspect when you lose anyone should come into my office and let’s have a conversation about what’s going on, you lose them.”

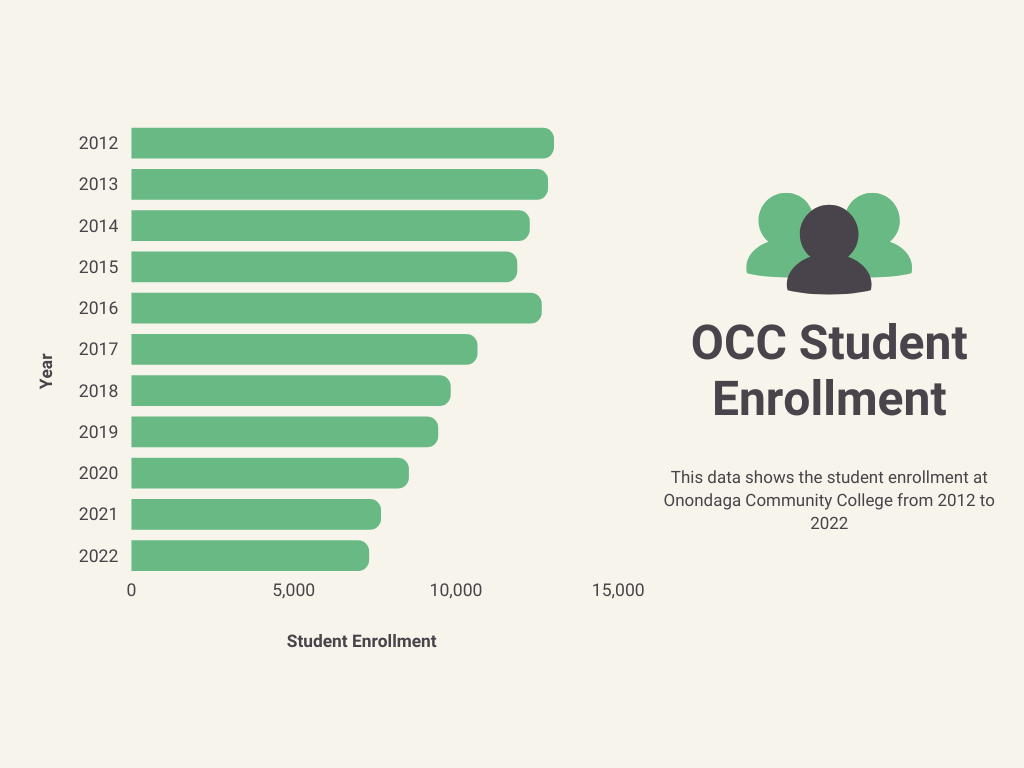

Across Syracuse, Onondaga Community College faced a similar problem with students stopping out because of the pandemic. Community colleges in New York have been facing a decline in overall student enrollment since around 2011, according to a study at Columbia University. This trend was no different at OCC, where enrollment was 13,081 in 2012 and fell every year until it reached 7,320 in 2022.

Roger Mirabito, the executive director of communications at OCC, said that the numbers were already going in the wrong direction and the pandemic only accelerated things.

One reason for this acceleration was that OCC could no longer hold in-person recruitment in local high schools. Another is that 80% of OCC students work 30 hours or more a week and had jobs that were shut down or decreased during COVID-19, making many students unable to afford the cost of college.

“It was really an uphill climb. There were a lot of kids who just kind of vanished in that spring 2020 semester,” Mirabito said. “Somebody would go home to New York City where they live in a small apartment with four or five family members and they’re trying to do schoolwork on a desktop so they don’t have somewhere else to go and just at some point, they just weren’t finishing.”

Despite setbacks, enrollment this semester at OCC is 3% ahead of the spring of 2022.

“We’re just we’re trying to be optimistic,” Mirabito said. “We think we’ve got a great product here with great value, and we just need to kind of reintroduce ourselves to the community and get people involved again and interested in coming here.”

Time away

Michael George knew that he had to get out of Syracuse. It was the fall of 2020 and on his first day of school, he contracted COVID-19.

“I was like this fucking sucks,” George said. “I was just sweating and couldn’t breathe like the Sheraton was a total dystopia.”

George stayed at school for another week or two before calling his mom to tell her he was unhappy.

“She was like well figure it out. And so I was like what would I do if I could do anything?” George said. “And I was like let’s go to Hawaii, it’s the farthest place from here and it’s still open.”

He looked up places he could work and found a bed and breakfast in Holualoha, a little part of Kona on the Big Island. He deferred to the next semester, hopped on a plane, and traded Syracuse for Hawaii.

Looking back on it, he said, it was pretty selfish of him to travel across the country during a global pandemic. But he said he’d totally do it again.

Despite this untraditional detour, he’s graduating a semester early and spent very little money in Hawaii overall since he was working for the bed and breakfast and later on, a Krishna-conscious comune. The money his parents had paid for that fall semester transferred over to the spring and he saw the different approaches to the pandemic. Though those in the cities followed CDC guidelines he also came across people who took a more holistic approach to the virus, opting out of vaccines for herbal remedies.

“My Western American Pennsylvanian world, upstate New York world changed and it was interesting,” he said.

Back on the east coast, Jordyn Pegues decided to take the whole year remote from her home in Virginia. As a Bandier student and singer, songwriter, and producer, staying at home allowed her to dedicate her time to her career. She was taking eighteen and a half credits, interning at a nonprofit, working at a boutique, and doing creative sessions for her music.

All this was possible because she was in an environment that she loved with all of her own space and home-cooked meals, she said.

“I would be in class and doing a session at the same time. I had a studio at home and just being at home afforded me so much more time because I wasn’t going to the dining hall and doing the random COVID testing that all you guys were doing,” Pegues said. “So I think that for me, the pandemic was very beneficial for my creative growth because it gave me time to really hone in on all my skills as a writer, producer, and an engineer.”

She did admit to having a bit of FOMO, or fear of missing out, at the beginning of her time at home. But soon enough she was too busy to focus on what she wasn’t experiencing on campus, she said.

“Obviously I love my friends and being away from them was hard, but like I knew it wouldn’t be forever,” she said. “And looking back on it I do not regret staying home one bit.”