Anxiety, powerlessness, and obligation: how SU Chinese students endure an era of perplexity

SU students offer support to Chinese protests

The past few weeks had been a period of unease for Chinese people as protests on a scale unprecedented since the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident erupted across the country. People across China called for the end of COVID lockdown and the removal of President Xi Jinping, who just secured his convention-breaking third term in October.

What sparked public frustration was a fire in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang in North Western China. On Nov. 24, a fire broke out in a residential high-rise. The city’s COVID lockdown, which lasted over three months, sealed entrances and exits in residential areas and hindered firefighters’ access. The flame killed 10 people and injured another nine, according to an official statement. On the same day, President Xi was reported to have sent grievances to the leader of the Solomon Islands in response to a recent earthquake, seemingly ignoring the domestic tragedy.

Throughout the world, Chinese nationals supported this rare act of defiance. Demonstrations and vigils were held internationally, mourning the deaths from the fire and calling to free Chinese people from harsh lockdowns and political constraints.

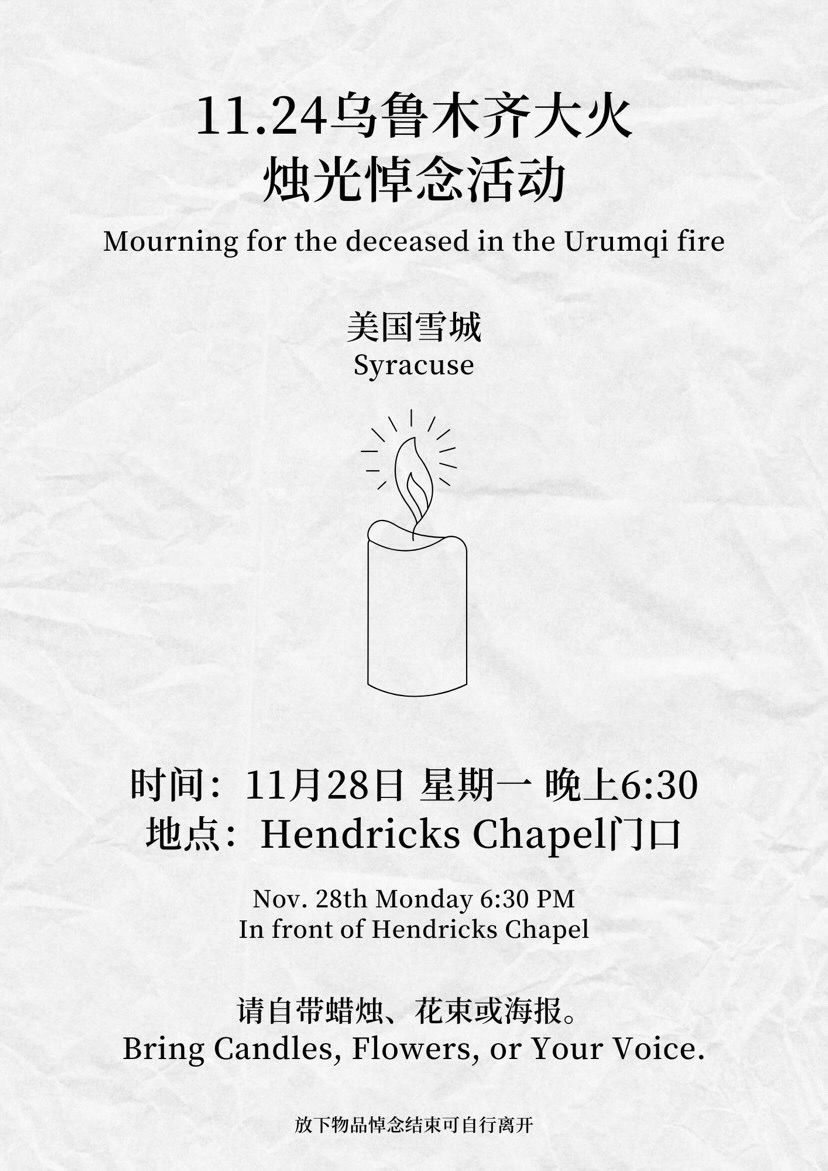

Chinese international students at Syracuse University held a vigil on Nov. 28 drawing a crowd to the steps of Hendricks Chapel that brought flowers, candles, and posters. Among those in attendance were some holding blank papers in protest of rampant censorship measures on the Chinese internet.

The Toll of China’s COVID Policy

Knowing about China’s COVID control measures is essential to understand how this fire accident in remote China became the last straw for Chinese people, whom are known for their political obedience.

The nation has been dealing with the virus differently from the rest of the world – in hopes of containing the virus, China shunned itself from international traveling, essentially creating a bubble with 1.4 billion people inside.

The intense zero-COVID policy was adopted nationwide. Traveling regulations were enforced from the provincial level down to individual residential buildings, enabled by routine societal-wise PCR tests, electric “traveling passes” showing individuals’ risk of exposure, and a vast mass of social workers known with their signature white hazmat suits.

This style of social control began with outstanding effectiveness and was praised outside China. Back in the August of 2021, when the rest of the world was dealing with infection spikes despite ongoing restrictions, Wuhan, the original epicenter of the virus, held a pool concert packed with thousands of visitors floating and dancing with their swimsuits, mask-free. The nation’s propaganda machine took no hesitation to credit this display of triumph to the “superior Chinese system,” with President Xi Jinping hailed as the leader and designer of the anti-COVID scheme.

Recently, however, with the more transmissive yet less deadly Omicron variant, the strict lockdown measure seemed ever more arbitrary. With the goal of the absolute eradication of COVID cases, cities were held to a halt, with inter-city travelings heavily restricted. Areas of “high-risk” were drawn across the country, putting residents into month-long lockdowns, sometimes blocking access to emergency services like ambulances and, in the Urumqi incident, fire departments.

A Vigil More than for Grieving

The vigil at Syracuse University started at 6:30 PM November 28, a chilly night with light snow. People gathered peacefully in front of the stairs of the Hedricks Chapel, lining up with candles and flower bouquets to honor the victims of the fire. Like a shrine, candles encircled a road sign paying homage to that of Urumqi Road in Shanghai, where a significant vigil, which sparked this now a global movement, took place days earlier.

Above all, the vigil, for many, was a space for grieving the dead. “Seeing my fellow countryman dying from an incident like this is heartbreaking,” said a junior student studying in International Relations, who declined to be named. “I feel paying my condolences is what I need to do.”

Beyond grieving, the event also made space for Chinese students to express their frustrations with the situation in their home country. Many questioned the brutish COVID lockdown measures. “I feel perplexed,” said the junior IR major. “The incident was a tragedy, and I couldn’t tell how should the COVID containment policy in China progress.”

Others were calling for a more liberal political environment at home. Students held a label advocating political freedom, with the hashtag “FREE CHINA” and the slogan “dictators out.” Blank printing papers, held by several students standing on the stairs, were too a symbol for showing political dissent: first used by a student in an individual protest at the Communication University of China in Nanjing on Nov. 26th, the blank paper soon became a widespread sign ridiculing the lacking of freedom of speech in China.

Rejections, Risks, Faced with a Sense of Duty

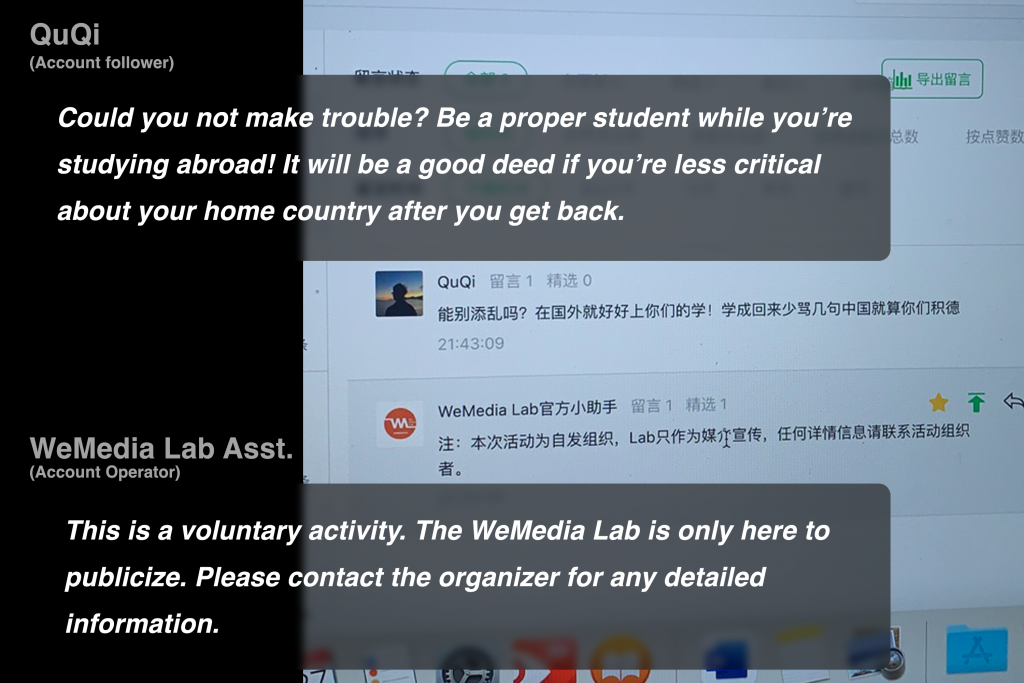

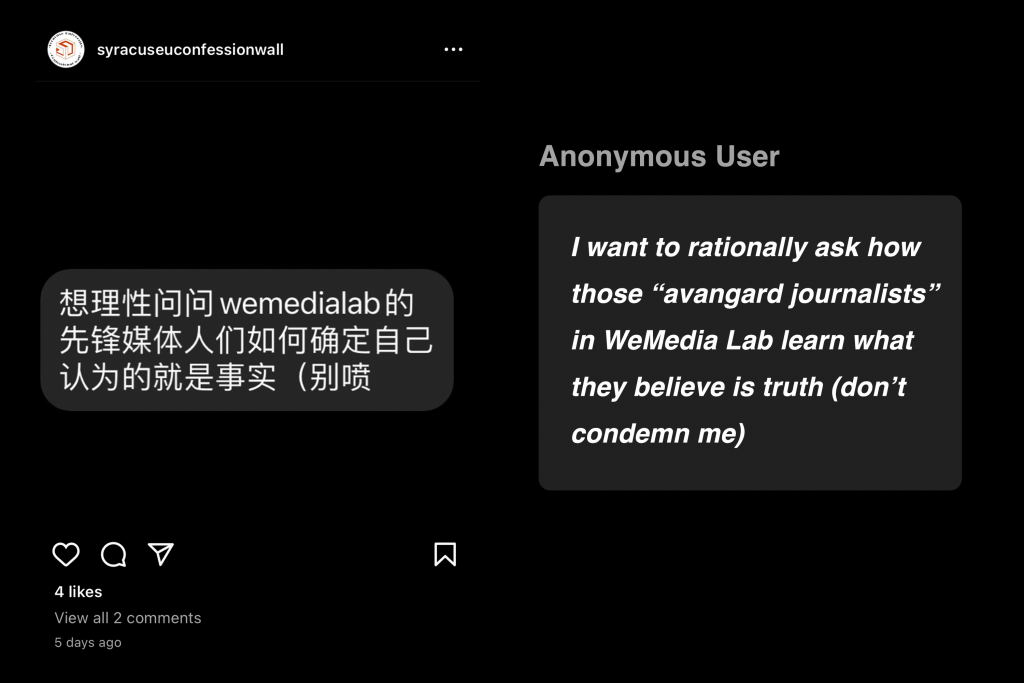

Because of the political implications of the event, just choosing to attend the vigil, for many, was a conflicting decision to make. Despite being out of the jurisdiction and potential prosecutions from the Chinese government, students still found it difficult to ignore sentiments opposing the vigil. According to a contributor of WeMedia Lab, a Chinese-language-based University-affiliated public account operating on WeChat, a post publicizing the vigil was reported and later taken down. A follower of the account responded to the advocation poster with a message calling students “not to make trouble” and “be proper students.” Instagram account @syracuseuconfessionwall, a platform collects and posts comments from Chinese-speaking students in SU, also received comments questioning the publicizing efforts from WeMedia Lab.

A WeChat users' comment of the vigil poster published by WeMedia Lab. Translated by the author.

Comment on Instagram by an anonymous user questioning the WeMedia Lab's publication efforts. Translated by the author.

Under the threat of being reported and having their identity exposed to the Chinese authorities, some students felt like they were risking the well-being of their relatives and themselves. Yet many were undeterred. One senior in anthropology said she felt stressed before going. “I was worried,” said the girl. “After all, my parents are still in China.” Although she considered herself to be “relatively cautious,” the student still found herself determined to stand at the front of the crowd. “I feel it was what I should do,” said the girl, “I wanted to join the movement, not as instigators but as actual participants.”

When asked why they chose to attend the vigil and undertake the risk, “it was the right thing to do” was the most common answer from the participant. “I was fulfilling my duty as a Chinese youngster,” said the senior anthropology major.

“I’m standing up for my own right,” explained a sophomore protester. “As a Chinese person, one’s either part of the oppressors or destined to become oppressed sooner or later. While I am not oppressed at the moment, someday I will lose my rights if I do not stand with the demonstrators in China today.”

Most of the participants were masked to offer some protection of their identity. Some remained maskless to make a statement. “I don’t feel it’s a good symbol for a protest against the COVID lockdown,” said a student who used the blank paper instead of a face mask to cover his face in the protest.

Yet many found comforts and protection from the masses. “Seeing so many people showing up was unexpected,” said the senior. “The crowd was welcoming and eased my concerns.” Seeing people supporting the cause also relieves her sense of loneliness. “I see myself living in a nomadic future, rejected by the culture of my homeland and striving to obtain my identity in a new country,” she explained. “I feel a lot less alone after the vigil.”

Besides courage, participants are nonetheless realistic about the effectiveness of their actions. “Our actions may end up not being that effective against an authoritarian government,” said a protester. The sophomore protester anticipated more participation from the crowd. “When I first saw a few people holding blank papers on the stair, I thought all of the crowd would end up joining them.” said a sophomore who was a part of the blank paper protest herself.

That does not mean, however, she was disappointed. Like many, she felt spirited seeing the movement emerging worldwide. “I was pretty pessimistic about the civil rights situation in China before,” she recalled. “Seeing recent protests, however, has been empowering nonetheless, even when it’s still difficult to see actual changes from those actions.”

What’s Next?

The wind of change, following recent updates, has seemingly started. Later last week, Guangzhou and Chongqing, two of the biggest cities in China, lifted the COVID restrictions. Urumqi, the city that inspired all protests, is also reported to have its strict lockdown measures eased.

This result for many, however, does not mean the time to call for a victory. “I don’t think my demands end with COVID restrictions,” said the senior, acknowledging her sense of powerlessness. “The political liberalization is still far from realization.” She called for further attention to the movement, “even for those among us coming from privileged backgrounds and haven’t felt the need to stand up.”

“All we can do is to care more about people around us,” said a junior vigil-goer. “Instead of sacrificing them in the name of abstract people.”