Slipping through the cracks of the U.S-Canada border

Slipping through the cracks

George Ero stubs out his cigarette, climbs into his taxi and blasts the heat. The early March evening is cold, even by Plattsburgh standards. Ero waits in a DunkinŌĆÖ Donuts parking lot that doubles as a Greyhound station in this northern New York town of about 20,000.

ŌĆ£They should be flocking in pretty soon,ŌĆØ he says, checking the time. ŌĆ£I try to give them safe passage and say they wonŌĆÖt see any cops. When I have any snacks, I offer them to them ŌĆō bags of peanuts. Some of them donŌĆÖt even bring any suitcases.ŌĆØ

The next Greyhound bus pulls in around 25 minutes late. Ero ambles over as passengers disembark.

ŌĆ£Roxham Road?ŌĆØ he asks. ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖre going to Roxham Road?ŌĆØ

A middle-aged man carrying a single backpack, containing all his lifeŌĆÖs belongings, says ŌĆ£yesŌĆØ and hops in the taxi, paying $90 for what will be around 30-minute ride to a sleepy road along the Canadian border – the last leg of a journey that began in Houston. HeŌĆÖs originally from Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, and is following a new migrant trail that developed over the last two years in a desperate bid for asylum in Canada that thousands like him have made. He says he knows no one in the country that awaits him.

Ero, who lost his job at a toy factory in Plattsburgh a few months ago, has ferried hundreds of people to the border, and he knows the route well. The sun sets as he approaches Roxham Road. He drops the Tanzanian man at a ditch that acts as the border between the United States and Canada. Canadian border patrol immediately confronts him, and explain that if he crosses, he will be arrested ŌĆō at which point he can make a claim for asylum. U.S. authorities are nowhere to be found.

The man walks across the border and into a processing facility, escorted by officers. The Canadian authorities ask Ero if anyone else is coming, then bids him goodnight.

Instances like these have become common on Roxham Road, located on the northern edge of Champlain, New York, 10 minutes from the Canadian border. Within three years, from 2015 to 2018, the number of migrants entering Canada has increased from about 32,000 to 110,000 per Canadian border patrol statistics.

Like the Tanzanian man who traveled across the country to get to the Canadian border, these asylum seekers endure long days and nights in search of a better a life. Many had hoped the United States would be a safe haven, only to encounter growing hostility towards immigrants and increased chances of deportation. Although they are being welcomed into Canada, their growing presence in the peaceful land of hockey and poutine has started to strain budgets and fray nerves.

But for now, the path into Canada remains open at Roxham Road ŌĆō a route unlike any other. Janet McFetridge, the mayor of Champlain, said about 900 asylum seekers cross this lowkey border every month ŌĆō and there are many reasons why.

Statistics from the Canadian border patrol show that most recently, the refugees that have been arriving are originally from the U.S., Haiti and Nigeria. The amount of migrants from the U.S. and Haiti respectively heightened in August 2017, just a few months after President Trump was inaugurated.

French-speaking asylum seekers specifically cross at Roxham because on the other side of the border awaits Quebec, where French is the official language. Besides language accessibility, Ero shares that refugees also come here because they want to get caught. Once they are arrested by the Canadian border patrol, they are welcomed into an inhabited part of Canada, where they can find themselves immersed in a happening city that provides them with a sense of security.

Traveling from what seems like worlds away, asylum seekers, like the Tanzanian man, heard of Roxham Road despite the distance. Via word-of-mouth, YouTube videos and online articles, refugees migrate over thousands of miles to claim safety to enter a new country and call it home.

Border beginnings

Beverly Maynard, 84,┬Āremembers moving to Champlain when she was just 7 years old and World War II had forced the country to ration food. Weekly trips to Canada consisted of traveling to complete simple tasks when times were tight, such as buying beef or using coupons to purchase cheaper water, Maynard said. She remembers crossing the border at Roxham Road as being fairly easy.

ŌĆ£You didnŌĆÖt have to have a passport,ŌĆØ Maynard said. ŌĆ£They just asked your name, where you were going and then ŌĆō okay! You were good to go.ŌĆØ

As she reflects on her childhood and teenage years, Maynard recalls how Roxham Road has transformed into the beacon for asylum seekers that it is today. What is now a road to a better life for refugees was once a simple path Maynard crossed regularly.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs very emotional to me, especially because I know how I used to be able to go across,ŌĆØ Maynard said. ŌĆ£I have fond memories of that area, too, so I think that makes it harder (to process the desperation of the refugees).ŌĆØ

From a quiet crossing to an avenue of escape

Maynard had not realized this road was being used for asylum seekers until her friend, McFetridge, had told her about it around two years ago.

McFetridge, who was deputy mayor at the time, was reading a Canadian newspaper when she stumbled upon an article about the influx of asylum seekers crossing the local border.

ŌĆ£When I found out that it was five miles from here, I was shocked,ŌĆØ McFetridge said. ŌĆ£I said something to Beverly because I knew she had known the area well.ŌĆØ

Once Maynard found out, she said she was just as surprised as her friend had been. She and McFetridge, who visits Roxham Road daily, went to the crossing together. Maynard became emotional.

ŌĆ£When these little kids looked at you, you could tell they were scared,ŌĆØ Maynard said of the asylum seekers. ŌĆ£They knew they had to go, but it was like, ŌĆśWhatŌĆÖs going to happen?ŌĆÖŌĆØ

With tears swelling in her eyes, Maynard said she doesn’t understand how people can be so cruel to the migrants.

Maynard is a regular at a local gym. She teaches a water fitness class, and both Canadians and Americans attend and actively participate together. Often, she said she overhears juicy gossip and side conversations in the womenŌĆÖs locker room. It is in the locker room where Maynard heard a woman discuss visiting Roxham Road, adding that she ŌĆ£went for the fun of it just to see what was going on.ŌĆØ

McFetridge gasped.

ŌĆ£They act like itŌĆÖs a little sideshow,ŌĆØ she said, ŌĆ£not like itŌĆÖs peopleŌĆÖs lives.ŌĆØ

Helping hands

McFetridge devotes an hour and a half, six days a week to visiting Roxham Road and helping refugees cross the border.

She collects winter clothes, toys and other accessories to provide to those crossing. Besides handing out items, she has one goal every time she goes: to make them feel like they matter.

ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖre so invisible,ŌĆØ McFetridge said. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs like the Underground Railroad, where they are crossing behind-the-scenes. But itŌĆÖs done in full light and yet they manage to do it fairly invisibly.ŌĆØ

McFetridge said that, many times, the asylum seekers tell her they will never forget her. Little do they know that she never forgets them.

She remembers a time when a refugee told her, ŌĆ£I have eight sisters and youŌĆÖre a new one to me.ŌĆØ She responded with a hug and told him she was happy to have him as a brother.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖll never forget that,ŌĆØ McFetridge said. ŌĆ£I truly have thousands and thousands of stories.ŌĆØ

McFetridge recalls a more recent memory, in which a family from Nigeria was awaiting at Roxham Road. She gave a brother and sister individual toys of their own, which she saw them play with as they crossed the border.

She said the bravery and perseverance of the refugees she meets inspire her.

ŌĆ£Could you do that?ŌĆØ McFetridge asked. ŌĆ£Could you go to some country that you donŌĆÖt know, donŌĆÖt know the language and say, ŌĆśHere I amŌĆÖ?ŌĆØ

On the other side

Paul Clarke, the executive director of the Canadian nonprofit Action R├®fugi├®s Montr├®al, works with refugees on a daily basis, providing them with the resources they need to acclimate to Canada.

He, too, began to hear of the increase in border crossings at Roxham Road in January 2017, which he assumes is because of President TrumpŌĆÖs immigration policies.

Clarke said many people on both sides of the border were willing to help soon after the news about Roxham began to spread.

He specifically remembers attending a meeting on the crossings and anticipated an unruly crowd. To his surprise, he left the meeting feeling hopeful and inspired by a comment from an elderly woman.

ŌĆ£She said, ŌĆśI live at the end of Roxham Road where my husband and I are always in our yard and see people walking with their suitcases all the time,ŌĆÖŌĆØ Clarke recalled. ŌĆ£ŌĆśWeŌĆÖre not scared. We say, ŌĆśWelcome to Canada.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Since then, Clarke has seen some opposition from Canadians when it comes to the money allocated to refugees. Federal elections will take place in October, and immigration remains a contentious political discussion.

ŌĆ£It is a bit of an issue, even for those with open hearts, even for those who think Canada has a role to play protecting people internationally,ŌĆØ Clarke said. ŌĆ£People are starting to get fed up.ŌĆØ

Sylvie Gauthier, a Canadian translator who works for the public healthcare system in Montreal, said she does not hear much of Roxham Road. She finds it surprising that it is still a popular way for refugees to seek asylum in Canada. Gauthier said she, personally, is open to accepting migrants in her country.

ŌĆ£We have so much,ŌĆØ Gauthier said. ŌĆ£When was the last time we were hungry? Not just, ŌĆśooh I want a snackŌĆÖ hungry, but really hungry.ŌĆØ

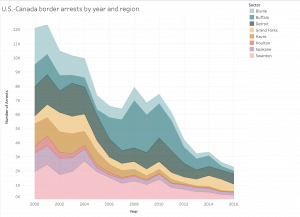

Asylum seekers who enter Canada from Roxham Road cross into Quebec and help make that province the No. 1 Canadian port of entry for asylum seekers. On the chart above, the colors on each bar represent a year, with 2018 at the bottom and 2016 at the top. The total height of the bar equals the total number of asylum seekers who entered that province during the four-year period 2015-2018. (Graphic by Justin Perline)

And the tide rolls north

On the same day the Tanzanian man arrived, McFetridge stood at the border as a husband and wife from Cameroon and man from Uganda hopped out of a taxi. She gave them hugs and new winter gear, exchanged a few hopeful words and stood beaming as they hauled their suitcases over the border to begin a new life.

As long as Roxham Road continues to see refugees every day, McFetridge says she will continue to show up six days a week with winter jackets and Barbie dolls in hand.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs really, really simple. ItŌĆÖs nothing special that IŌĆÖm doing,ŌĆØ McFetridge said. ŌĆ£I insert myself to give them (refugees) that tiny bit of hope that somebody cared about them before they left.ŌĆØ